This month, we recognize 150 years of a phenomenon that started in Detroit but has become a national icon: Vernors. In 1866, pharmacist James Vernor began serving his zippy ginger ale at his pharmacy’s soda fountain, and it became first a local, then a regional favorite. Today, Vernors is owned by Dr Pepper Snapple Group, a major North American beverage company, and can be found throughout the United States. Many Detroiters retain a particularly strong loyalty to the fizzy concoction, swearing by both its taste and its ability to soothe an upset stomach—so much so that the Detroit Historical Society has organized a week-long anniversary celebration. In recognition of the milestone, we dug through our collections for some Vernors-related artifacts, and turned up labels, signs, photos of delivery trucks, a recipe booklet, and, perhaps most intriguingly, several photos like this one of James Vernor III sitting in a Vernors-branded Ford amphibious jeep. We haven’t yet been able to turn up the full story behind these images, but suspect they might relate to clearing surplus inventory of such vehicles after World War II. We invite you to pop open a refreshing ginger ale of your own and browse the rest of the Vernors-related items we found in our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 20th century, 19th century, Michigan, digital collections, Detroit, by Ellice Engdahl, beverages

Garage Art

Photo by Bill Bowen.

Model T mechanics are restoration artists in their own right.

The Henry Ford has a fleet of 14 Ford Model T’s, 12 of which ride thousands of visitors along the streets of Greenfield Village every year.

With each ride, a door slams, shoes skid across the floorboards, seats are bounced on, gears are shifted, tires meet road, pedals are pushed, handles are pulled and so on. Makes maintaining the cars and preserving the visitor experience a continuous challenge.

“These cars get very harsh use,” said Ken Kennedy, antique vehicle mechanic and T Shed specialist at The Henry Ford. “Between 150,000 and 180,000 people a year ride in them. Each car gives a ride every five to seven minutes, with the longest route just short of a mile. This happens for nine months a year.”

The T Shed is the 3,600-square-foot garage on the grounds of Greenfield Village where repairs, restoration and maintenance magic happen. Kennedy, who holds a degree in restoration from McPherson College in Kansas, leads the shed’s team of staff and volunteers — many car-restoration hobbyists just like him.

“I basically turned my hobby into a career,” quipped Kennedy, who began restoring cars long before college. His first project: a 1926 two-door Model T sedan. “I also have a 1916 Touring and a 1927 Willys-Knight. And I’m working on a Model TT truck,” he added.

April through December, the shed is humming, doing routine maintenance and repairs on the Model T’s as well as a few Model AA trucks that round out Greenfield Village’s working fleet. “What the public does to these cars would make any hobbyist pull their hair out. Doors opening and shutting with each ride. Kids sliding across the seats wearing on the upholstery,” said Kennedy. Vehicles often go through a set of tires every year. Most hobbyist-owned Model T’s have the same set for three-plus decades.

With the heavy toll taken on the vehicles, the T Shed’s staff often makes small, yet important, mechanical changes to the cars to ensure they can keep up. “We have some subtle things we can do to make them work better for our purpose,” said Kennedy. Gear ratios, for example, are adjusted since the cars run slow — the speed limit in Greenfield Village is 15 miles per hour, maximum. “The cars look right for the period, but these are the things we can do to make our lives easier.”

In the off-season, when Greenfield Village is closed, the T Shedders shift toward more heavy mechanical work, replacing upholstery tops and fenders, and tearing down and rebuilding engines. While Kennedy may downplay the restoration, even the conservation, underpinnings of the work happening in the shed, the mindset and philosophy are certainly ever present.

“Most of the time we’re not really restoring, but you still have to keep in mind authenticity and what should be,” he said. “It’s not just about what will work. You have to keep the correctness. We can do some things that aren’t seen, where you can adjust. But where it’s visible, we have to maintain what’s period correct. We want to keep the engines sounding right, looking right.”

Photo by Bill Bowen.

RESTORATION IN THE ROUND

Tom Fisher, Greenfield Village’s chief mechanical officer, has been restoring and maintaining The Henry Ford’s steam locomotives since 1988. “It was a temporary fill-in; I thought I’d try it,” Fisher said of joining The Henry Ford team 28 years ago while earning an engineering degree.

He now oversees a staff with similarly circuitous routes — some with degrees in history, some in engineering, some with no degree at all. Most can both engineer a steam-engine train and repair one on-site in Greenfield Village’s roundhouse.

“As a group, we’re very well rounded,” said Fisher. “One of the guys is a genius with gas engines — our switcher has a gas engine, so I was happy to get him. One guy is good with air brake systems. We feel them out, see where they’re good and then push them toward that.”

Fisher’s team’s most significant restoration effort: the Detroit & Lima Northern No. 7. Henry Ford’s personal favorite, this locomotive was formerly in Henry Ford Museum and took nearly 20 years to get back on the track.

“We had to put on our ‘way-back’ hats and say this is what we think they would have done,” said Fisher.

No. 7 is one of three steam locomotives running in Greenfield Village. As with the Model T’s, maintaining these machines is a balance between preserving historical integrity and modernizing out of necessity.

“A steam locomotive is constantly trying to destroy itself,” Fisher said. “It wears its parts all out in the open. The daily firing of the boiler induces stresses into the metal. There’s a constant renewal of parts.”

Parts that Fisher and his team painstakingly fabricate, cast and fit with their sturdy hands right at the roundhouse.

DID YOU KNOW?

The No. 7 locomotive began operation in Greenfield Village to help commemorate Henry Ford’s 150th birthday in 2013.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Keeping the Roundhouse Running

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Part Two: Number 7 is On Track

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, trains, The Henry Ford Magazine, railroads, Model Ts, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, engineering, collections care, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Remembering John Margolies

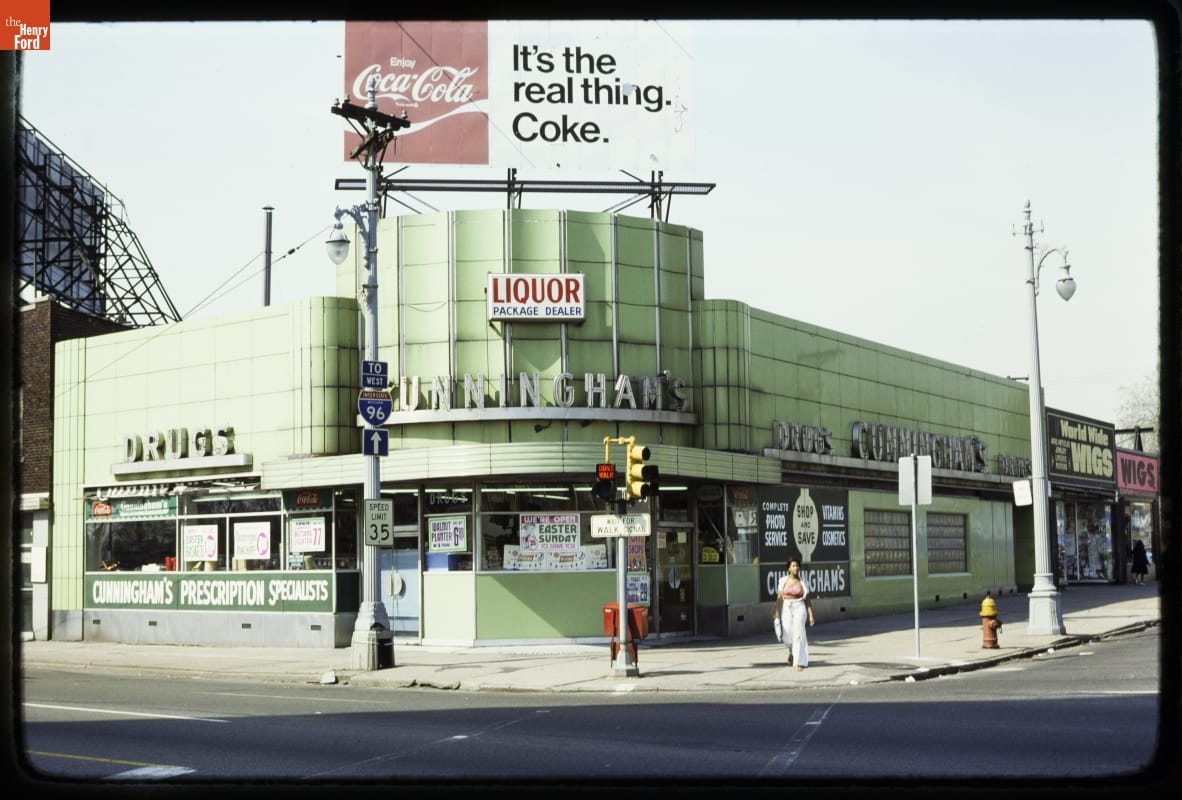

Cunningham Drugs, Detroit, Michigan, 1976. THF 239803

It is with great sadness that we hear of the passing of John Margolies.

Elwood Bar, Detroit, Michigan, 1986. THF 239044

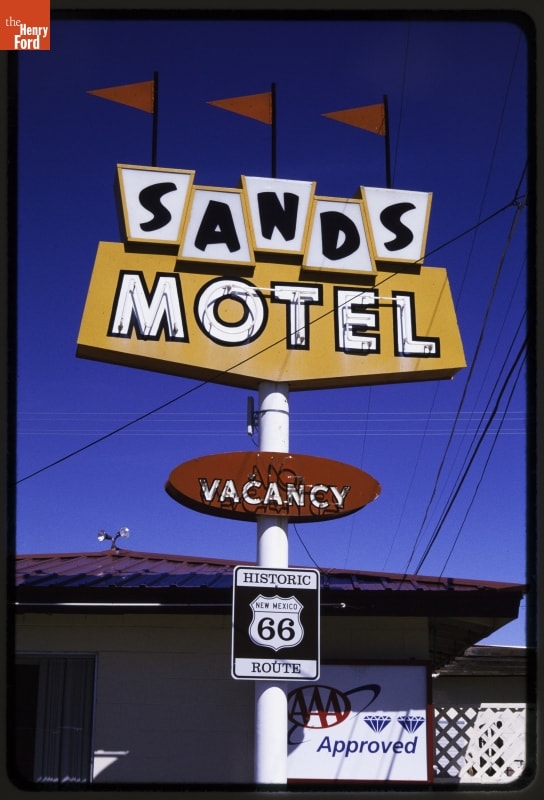

John was motivated the same way many photographers with a deep appreciation for history are: he wanted to capture things that had become overlooked, structures that were endangered, vulnerable, and on the brink of destruction. But rather than choosing a neighborhood, or town or region he chose what could be found along the edges of all the old roads, the pre-interstate routes stretched throughout the United States—like a local historian of endless highways. His finest images look like stills from a perfect road movie, and they capture an element of the nation’s essence and identity—mom and pop businesses, motels, diners, crazy signage and attractions, clamoring for the attention of motorists, played out against distance and motion.

A large selection of John’s photographic slides were acquired by The Henry Ford in 2013; John also donated a great many roadside-related souvenirs and other items.

The museum’s exhibit Roadside America: Through the Lens of John Margolies ran from June 2015 to January 2016. Continue Reading

roads and road trips, popular culture, Roadside America, John Margolies, photography, photographs, in memoriam, by Marc Greuther

An Artist Visits the Bugatti

Since 1929, The Henry Ford has hosted a steady stream of celebrity visitors, eager to see our iconic artifacts. In 1961, French artist and iconoclast Marcel Duchamp and his wife visited Henry Ford Museum. If you know Duchamp’s history, you might find it an interesting contrast that the man who rejected art that was merely beautiful in favor of art “in the service of the mind” stopped to pose for this photo in front of the Bugatti. The large, luxurious, and beautiful car seems a far cry from “Fountain,” created by Duchamp more than four decades before. We’ve just digitized dozens of images featuring celebrities of all stripes visiting our campus over many decades—browse more by visiting this Expert Set we’ve created within our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 20th century, 1960s, luxury cars, Henry Ford Museum, Driving America, digital collections, convertibles, cars, by Ellice Engdahl, art

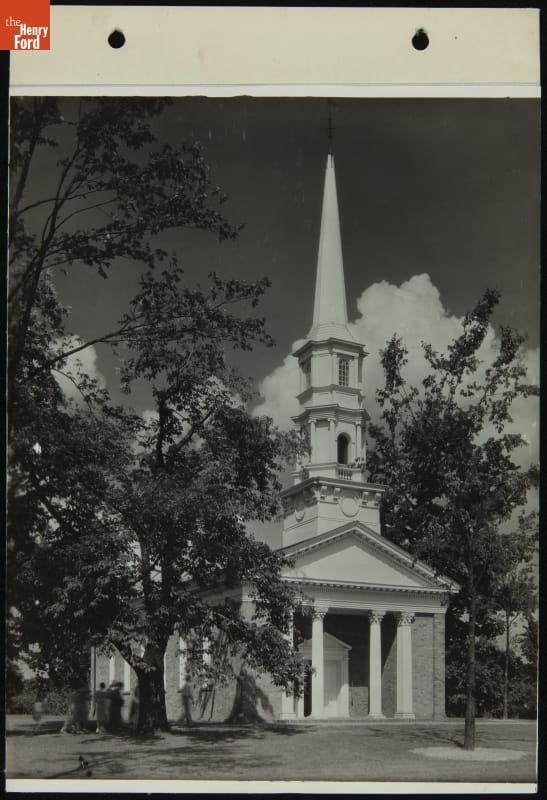

You could argue that one of the most visible buildings in Greenfield Village is Martha-Mary Chapel, standing as it does at the end of the Village Green, with its columns in front and high steeple. However, unlike many of the other buildings in the Village, the Chapel is not a historic building that was moved from elsewhere, but was built in the Village in 1929. Henry Ford wanted to recreate a typical village green and therefore had the Chapel (a characteristic building for a green) built, and named it after both his own mother, Mary Litogot Ford, and his wife Clara’s mother, Martha Bench Bryant. Some of the fixtures on the building came from Clara Ford’s childhood home, adding another layer of personal resonance. We’ve just digitized more than 100 images of the Chapel taken over its nearly 90-year history, including this classic shot from 1935—browse them all by visiting our Digital Collections.

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

Clara Ford, Henry Ford, Ford family, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, digital collections, by Ellice Engdahl

Artifact Insight: Confederate Bass Drum

Confederate Bass Drum, Captured at Missionary Ridge, 1860-1863. Gift of the Jewell Family. THF159778

Confederate Bass Drum, Captured at Missionary Ridge, 1860-1863. Gift of the Jewell Family. THF159778

This drum was likely left behind by fleeing Confederates as Union soldiers drove them from the hill during the battle of Missionary Ridge, part of the Chattanooga Campaign in Tennessee, on November 25, 1863. The astonished Confederates panicked, broke rank, and fled pell-mell. A Union victory. In less than a year and half, the Civil War would end and the Union would be preserved.

The abandoned drum was probably picked up from the battlefield by a member of the 38th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, a Union unit that participated in the Missionary Ridge assault.

This battlefield souvenir was then taken to Fulton County, Ohio, where it was preserved by members of the local Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), an organization of Union veterans. By the 1880s, Fulton County had about 11 G.A.R. posts. To these Union veterans, this drum symbolized victory over Confederate forces. The drum was likely displayed in the G.A.R. hall at Wauseon in Fulton County.

A few days before the Missionary Ridge battle, Abraham Lincoln gave his eloquent Gettysburg Address in Pennsylvania. For us today, this drum symbolizes the end of the Civil War and the “new birth of freedom” spoken of so memorably by Abraham Lincoln on that day.

musical instruments, music, Grand Army of the Republic, Civil War, by Jeanine Head Miller

Fraternity, Charity, Loyalty: Remembering the Grand Army of the Republic

Detroit's Bagley Memorial Fountain stands amidst a banner and festive decorations in its original location at Woodward Avenue and Fort Street. This photograph may have been taken during a Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) Memorial Day celebration. A society for Union Civil War veterans, the G.A.R. began observing the holiday - originally called Decoration Day - in 1868. THF 202914

When Civil War veterans returned home after the conflict they established their own fraternal organizations, helping one another remember and heal from their shared experiences. This year marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.) in Decatur, Illinois. The G.A.R. was a fraternal organization made up of Civil War veterans who fought and served for the Union.

Veteran Robert Burns Beath, writing in 1888 of the returning home of veterans said, “They were soon to part, each in his own way to fight the battle of life, to form new ties, new friendships, but never could they forget the sacred bond of comradeship welded in the fire of battle, that in after years, should be their stimulus to take upon themselves the work confided to the people by President Lincoln ‘to bind up the Nation’s wounds,’ ‘to care for him who shall have borne battle, and for his widow and his orphan.”

This unique “bond of comradeship” would be the catalyst for veterans to join together in influencing a nation still reeling from the aftermath of war. Under the watch-words “Fraternity, Loyalty, and Charity” the G.A.R. set out to serve their brothers in arms as well as loved ones left behind by the fallen through charitable initiatives.

Did you know?

The G.A.R. helped establish May 30 as Memorial Day—or Decoration Day as it was then known—asking members to decorate the graves of their fallen comrades with flowers on May 30, 1868.

Grand Army of the Republic, veterans, Civil War, by Steve LaBarre, by Becky Young LaBarre

Presidential Limousines at The Henry Ford

The Henry Ford was excited to once again welcome author and former Secret Service Agent Clint Hill, along with journalist Lisa McCubbin, to Henry Ford Museum this spring in celebration of his latest book, Five Presidents: My Extraordinary Journey with Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, and Ford.

More about Mr. Hill and our presidential limousines:

Clint Hill on Presidential Limousines

Presidential Vehicles

Looking Back: JFK Remembered at Henry Ford Museum

Protecting our Presidents

Turning Point

In honor of Mr. Hill's visit to The Henry Ford, Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson put together this overview of the presidential limousines found within on exhibit at Henry Ford Museum. Learn more below.

A presidential parade car provides two things: visibility and security. Those concepts are often at odds. The Henry Ford’s presidential Lincolns illustrate the difficult and changing balance between the chief executive’s need to be seen and need to be safe.

“Sunshine Special,” the 1939 Lincoln Model K most often associated with Franklin D. Roosevelt, was the first parade car specifically modified for presidential use. Coachbuilder Brunn & Company focused more on utility than luxury, deleting armrests for maximum seating capacity and adding wide running boards for Secret Service agents. The car was not armored until Pearl Harbor, when bullet resistant tires, glass and armor plating were installed.

In 1950, Harry S. Truman took delivery of a new Lincoln with a body by Raymond Dietrich, but the car was used most often by successor Dwight D. Eisenhower. Again there was no armor, but in 1954 the limo received the weatherproof plexiglass roof that inspired its nickname, the “Bubbletop.” Security features did not extend much beyond riding steps on the rear bumper and flashing red lights at the front.

Planning for the next car started under Eisenhower, but the 1961 Lincoln Continental limo is forever tied to John F. Kennedy. Once again, armor was not considered necessary, and Kennedy preferred to travel with the top removed whenever possible. But his assassination ended the tradition of open cars. Ford and custom car builder Hess & Eisenhardt rebuilt the 1961 Lincoln with a permanent roof, titanium armor and bullet-resistant glass five layers thick.

The 1972 Lincoln limousine was the first presidential parade car designed and built as an armored vehicle from the start. Security was now of prime importance – a point dramatically underscored when Ronald Reagan suffered an attempt on his life while getting into the limo in 1981.

The Henry Ford’s presidential Lincolns were leased to the White House. As the leases ended, the cars returned to Ford Motor Company and the firm gifted them to the museum. Currently, Cadillac supplies the president’s state cars. Each is custom-built – most recently on truck platforms – and each is typically destroyed at the end of its service life.Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Looking Back: JFK Remembered at Henry Ford Museum

- The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation: Presidential Limousines

- Morgan Gies: Driver to the Presidents

- Protecting Our Presidents

20th century, presidents, presidential vehicles, limousines, JFK, Henry Ford Museum, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson

Over the years, sporting events have become traditions in our lives: the Super Bowl in the winter, the Kentucky Derby every May, and the Indianapolis 500 on Memorial Day Weekend. Iconic events such as these develop their own customs over time, and the Indianapolis 500 is no exception. As we celebrate the 100th running of the race on May 29, here is a look at a few of the traditions that have developed over the years.

Start of the 1911 Indianapolis 500. P.O.2703

Some of the current Indy traditions started in the early days of the race. Since the inaugural running on May 30, 1911, the contest has always been held on Memorial Day or that weekend. As a tribute to horse racing practices, only the winner of the race (and his team) are honored in Victory Lane, without a podium for the top three finishers. Speaking of victory celebrations, Lewis Meyer began another triumphal tradition in 1936. After winning that year's race, Meyer grabbed a bottle of buttermilk to cool himself down, as he typically did on hot days. After an executive from the Milk Foundation saw a photograph of the celebration, it became a yearly occurrence. Although there have been a few years without milk in Victory Lane, this appears to be a tradition that will last for years to come.

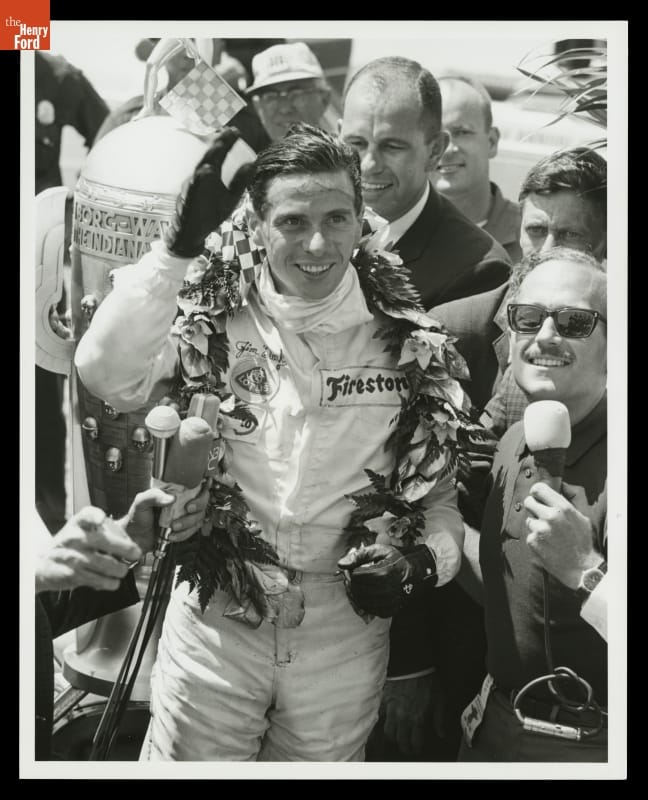

Bobby Unser drinking milk in Victory Lane, 1968, 2009.158.317.5507

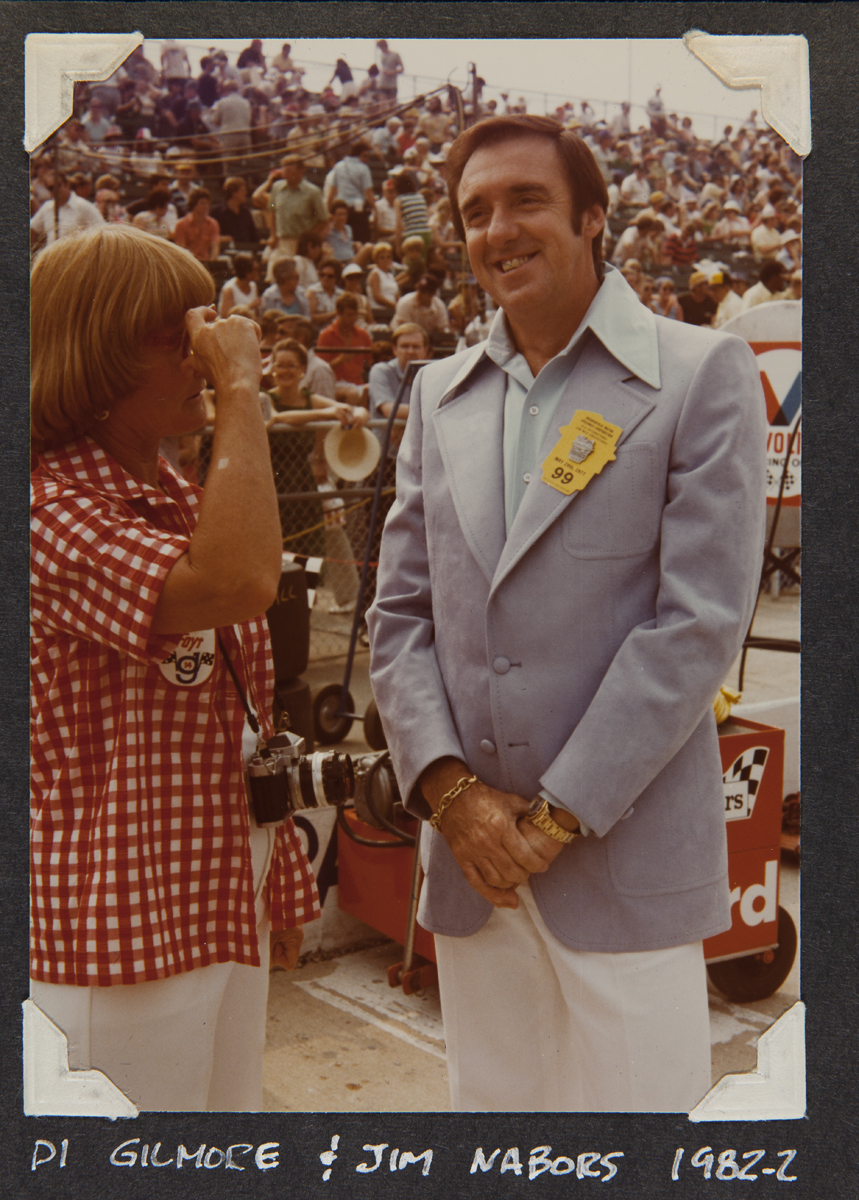

The 1940s saw the start of more traditions at the Indianapolis 500. In 1946, the song "Back Home Again in Indiana" was first played in pre-race festivities. Numerous artists have been enlisted to perform the song over years, including Jim Nabors, who sang it 36 times between 1972 and 2014. (Singer Josh Kaufman will fulfill the duty for this year.) In 1947 Grace Smith Hulman, the racetrack owner's mother, suggested balloons be released before the start of the race. Since 1950, 30,000 multicolored balloons, now made of biodegradable latex, have been let loose coinciding with the final notes of "Back Home Again in Indiana."

Di Gilmore and Jim Nabors at the 1977 Indy 500

Balloon release at the 1963 Indy 500. 2009.158.317.1729

The next decades brought more long-lasting traditions to the Indianapolis 500. In 1953, Wilbur Shaw first gave the starting call of "Gentlemen, start your engines!" Some variation of this call has been used every year since then, with the opening periodically changing to "Lady and Gentlemen" or "Ladies and Gentlemen" for the years when female drivers are competing. A few years later, the 500 Festival Parade developed after local newspaper columnists noted the community festivities that accompanied the Kentucky Derby. The 2016 festival includes a mini-marathon, parade, children's activities, and the Snakepit Ball. It was 1960 that was the first year that the winner was adorned with a wreath, drawing from Grand Prix traditions. The current wreath design contains 33 white cymbidium orchids representing the 33 cars and drivers on the starting grid.

Jim Clark draped in victor's wreath at the 1965 Indy 500. 2009.158.91

1968 Indy Festival Queen with the Borg Warner Trophy, 2009.158.317.5261

Since the 1970s, more traditions have been added to the Indy 500. The Last Row Party, started in 1972, is a charity function held the Friday before the race. In addition to raising scholarship funds for local students, the party also serves as a roast for the last three competitors to make the starting grid. A few years later, in 1976, Jeanetta Holder created and presented her first quilt to the winner of the race. Over the years, she has crafted more than 40 hand-stitched quilts, with Bobby Unser's 1981 quilt now in the collection of the Henry Ford. More recent additions to the Indy traditions include concerts on Carb Day and Legends Day, and the kissing of the bricks, which actually started in NASCAR tradition in 1996. Gil de Ferran was the first Indy driver to do it at the conclusion of the 2003 race.

Jeanetta Holder quilt for Bobby Unser, 1981. 2009.171.18

Tradition and ritual are a part of our everyday lives, and will certainly be an integral part of this year's Indianapolis 500. Over the last 99 contests, drivers, owners, and even fans have created new customs that add to the history and lore of the race. As you watch the 100th running of the Greatest Spectacle in Racing on May 29, keep your eyes open for the existing traditions and perhaps some new ones in the making.

Janice Unger is Digital Processing Archivist for Racing, Archives & Library Services, at The Henry Ford.

Indiana, 21st century, 20th century, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Indy 500, by Janice Unger

The Bogus Brewster Chair

When an article was published in 1977 about a sculptor who had built a certain armchair in the 1960s — not to make a fake, but to make a point about his skill and ability to fool the experts — The Henry Ford took note. The throne-like chair described in the story was uncannily similar in every way to a 17th-century piece The Henry Ford had acquired in 1970 as a highly prized and rare Brewster, a type of chair associated with William Brewster, one of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Conservation science and strong detective work did prove the chair to be a fake, and The Henry Ford admitted to being fooled. Always an institution dedicated to education, The Henry Ford didn’t remove the chair, instead keeping it as a reminder of a lesson learned and even loaning it out for national exhibits on fakes and forgeries.

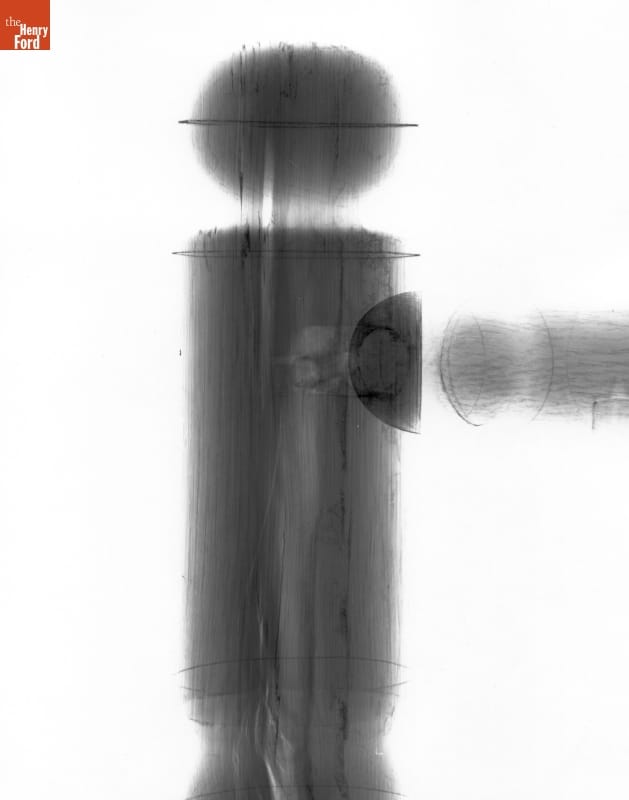

An X-ray of The Henry Ford’s Brewster chair forgery showed that the drill bits used for making the holes that received the turned spindles had a modern-day pointed end rather than the spoon shape associated with bits common to carpentry in the 1600s.

DID YOU KNOW?

William Brewster was one of 102 passengers who traveled across the Atlantic on the Mayflower in 1620 to establish Plymouth Colony.

Chairs were rare in 17th-century American homes. Chairs like the Brewster were made for honored guests or the head of the household — intended to impress visitors and confirm the sitter’s status and position. And they were not very comfortable.

The Henry Ford Magazine, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, decorative arts, furnishings