Posts Tagged #behind the scenes @ the henry ford

Moving Modern Mobility

The original paint surface on the 1967 Ford Mark IV race car is very unstable. The Stringo helps us move the car with minimal handling.

Moving cars can seem like a no-brainer – they are designed to move, and they are at the core of our modern understanding of mobility. Much of our modern infrastructure, from roads and bridges to GPS satellites, is designed around getting cars to move from place to place quickly and efficiently. Cars that drive themselves seems a likelihood that is just around the corner.

So moving cars that are part of museum collections shouldn’t be a big deal, should it? Well, you’d be surprised.

The Henry Ford has over 250 cars, trucks, and other motorized vehicles in its collection, and each presents its own special set of problems when it comes moving them. To start, we keep only a handful of cars operational at any one time, and even those that are operational can’t be run indoors. So we have to push cars, which has the effect of making every little detail about the cars a big deal.

Do the tires hold air? Do the wheels roll? Do the brakes work? Does the transmission and drivetrain move freely, or is the engine stuck in gear? What kind of transmission does it have? How heavy is the car? Is it gas, electric or steam powered? Does the car need electric power to release the steering or move the transmission? What parts of the car body can be touched? Is the paint stable or flaking; is it original or was the vehicle repainted? Is the interior original or replaced? Can you sit on the seats or hold the steering wheel? All of these questions and more go into our decisions about how were go about moving one of our historic vehicles.

We make use of a variety of tools to help us move cars: dollies, rolling service jacks, Go-Jaks ®, flat carts or rolling platforms, slings, and forklifts. Some cars are easy, and move into place with one person steering and a few pushing. We use dollies or rolling jacks to move the car in tight quarters, or if the wheels don’t roll properly. Other cars are more problematic – we’ve even removed body sections of cars with fragile paint, to avoid having to push on those surfaces. Others have fragile tires which can’t even support the weight of the car. Moving a car like that is more like moving a large sculpture than a vehicle.

Recently, we’ve added a new tool to our car-moving toolbox. Thanks to a generous gift from the manufacturer, we’ve acquired a Stringo ® vehicle mover. It’s a bit like an electric pallet jack for cars – it picks up and secures two wheels of a car and then pulls or pushes the car where ever it needs to go. We can make car moves now with just one or two people, instead of as many as six, and can do it almost without touching the car at all.

We moved this 1901 Columbia Electric Victoria on floor jacks. The tires were old and brittle, so they rolled poorly.

The Goldenrod, a 1965 land speed racer, had its own set of rolling gantries for moving.

This 1950 Chrysler New Yorker can roll on its own tires.

To get this 1959 Cadillac up onto an exhibition platform, we needed to get it on dollies, and roll it up a ramp.

Our Stringo captures the front wheels of the 1964 Mustang and moves it, so a car can be moved by one person.

With hundreds of car moves ahead of us in the not-too-distant future, we are looking forward to making good use of our new Stringo ®.

Jim McCabe is former Special Projects Manager at The Henry Ford.

philanthropy, cars, by Jim McCabe, collections care, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Behind the Scenes with IMLS: Recent Progress

There has been a lot going on at The Henry Ford lately – our Beatles exhibit has just closed, the new Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery is soon to open, and the conservation department has been involved with those goings-on and more. Even though there’s a lot of change and activity, our IMLS-funded grant project to work on our electrical collections continues at a steady pace. As we approach the halfway point in the grant, we are also approaching 450 objects conserved – the halfway point of our 900-object goal!

There has been a lot going on at The Henry Ford lately – our Beatles exhibit has just closed, the new Davidson-Gerson Modern Glass Gallery is soon to open, and the conservation department has been involved with those goings-on and more. Even though there’s a lot of change and activity, our IMLS-funded grant project to work on our electrical collections continues at a steady pace. As we approach the halfway point in the grant, we are also approaching 450 objects conserved – the halfway point of our 900-object goal!

Conservation Specialist Mallory Bower and Senior Conservator Clara Deck clean objects in the Collections Storage Building.

We have been continuing to make regular trips to our Collections Storage Building (CSB) to select artifacts for inclusion in the grant; while we’re out there, we give them an initial clean, before bringing them into the museum to be fully conserved, then photographed and packed.

Collections Specialist Cayla Osgood brings down the dynamo on a forklift while Mallory “spots”, keeping a watchful eye for corners, overlapping edges, or any other potential issues.

We have recently brought our third “extra-large” object in from CSB, an Eickemeyer Dynamo. When choosing objects to bring in, we take into account the wants and needs of other departments of the museum, and we chose this object as there was some interest in it from the curatorial department. Since it was high up on a shelf, it had been a little while since they were able to inspect it up-close – there was a lot of excitement when we brought it in! Although it will not be going on display, it is now clean and accessible, and soon it will be digitized and available online.

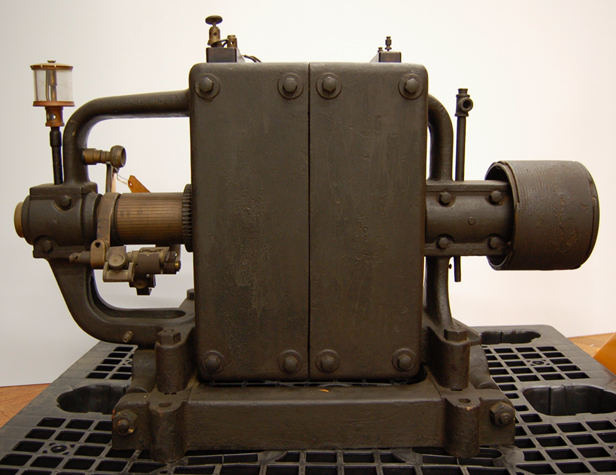

The Eickemeyer Dynamo, retrieved from storage (32.107.1)

The dynamo did not need an excessive amount of treatment, largely a brush/vacuum to remove storage dust, plus removal of a little copper corrosion on some of the fittings on the ends. (Want to read more about our “extra-large” objects? Check out our previous blog post!)

A circuit breaker with a marble base, during treatment (29.1333.292)

Although the “extra-large” objects have been focused on quite a bit in our blogs, most of what we do involves much smaller objects. There are so many different materials and types of objects, we have a lot of interesting challenges to work through. Something of particular note that we have come across a few times now is objects with marble bases, like this circuit breaker. The marble is frequently very dirty, with staining and significant accretions, and, as in this case, also cleans up fairly well! This “in progress” shot shows how different the object can look from when we get it out of the Collections Storage Building to when it’s clean and finished, ready to be digitized and packed.

So that’s where we stand currently, nearly halfway through our IMLS grant, working away on lots of electrical objects. Keep your eyes peeled for future blog posts with updates on our progress!

Louise Stewart Beck is former IMLS Project Conservator at The Henry Ford.

power, electricity, IMLS grant, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, collections care, conservation, by Louise Stewart Beck

Behind the Scenes with IMLS: Cleaning Objects

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting.

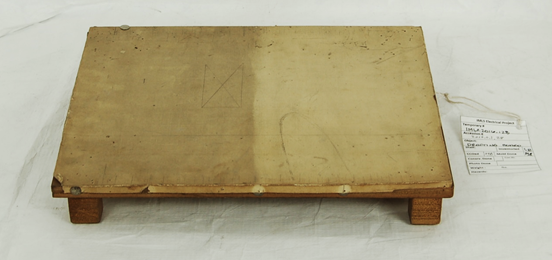

One of the main components of The Henry Ford’s IMLS-funded grant is the treatment of electrical objects coming out of storage. This largely involves cleaning the objects to remove dust, dirt, and corrosion products. Even though this may sound mundane, we come across drastic visual changes as well as some really interesting types of corrosion and deterioration, both of which we find really exciting. An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

An electrical drafting board during treatment (2016.0.1.28)

Conservation specialist Mallory Bower had a great object recently which demonstrates how much dust we are seeing settled on some of the objects. We’re lucky that most of the dust is not terribly greasy, and thus comes off of things like paper with relative ease. That said, it’s still eye-opening how much can accumulate, and it definitely shows how much better off these objects will be in enclosed storage.

Before and after treatment images of a recording & alarm gauge (2016.0.1.46)

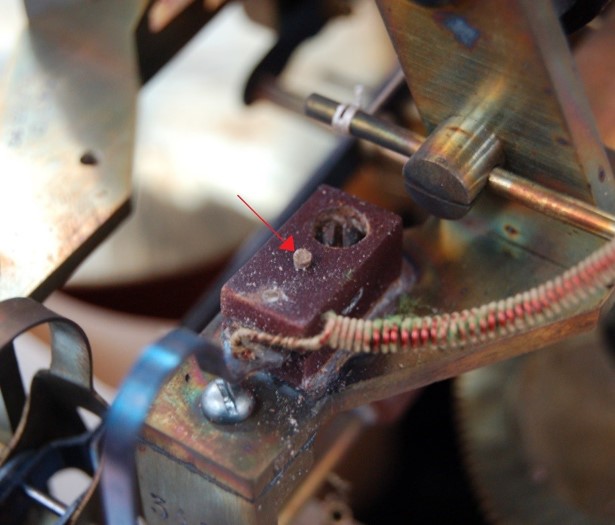

The recording and alarm gauge pictured above underwent a great visual transformation after cleaning, which you can see in its before-and-after-treatment photos. As a bonus, we also have an image of the material that likely caused the fogging of the glass in the first place! There are several hard rubber components within this object, which give off sulfurous corrosion products over time. We can see evidence of these in the reaction between the copper alloys nearby the rubber as well as in the fogging of the glass. The picture below shows where a copper screw was corroding within a rubber block – but that cylinder sticking up (see arrow) is all corrosion product, the metal was actually flush with the rubber surface. I saved this little cylinder of corrosion, in case we have the chance to do some testing in the future to determine its precise chemical composition.

Hard rubber in contact with copper alloys, causing corrosion which also fogged the glass (also 2016.0.1.46). Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

Hard rubber corrosion on part of an object – note the screw heads and the base of the post.

This is another example of an object with hard rubber corrosion. In the photo, you can see it ‘growing’ up from the metal of the screws and the post – look carefully for the screw heads on the inside edges of the circular indentation. We’re encountering quite a lot of this in our day to day work, and though it’s satisfying to remove, but definitely an interesting problem to think about as well.

There are absolutely more types of dirt and corrosion that we remove, these are just two of the most drastic in terms of appearance and the visual changes that happen to the object when it comes through conservation.

We will be back with further updates on the status of our project, so stay tuned.

Louise Stewart Beck is Senior Conservator at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, conservation, collections care, by Louise Stewart Beck, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

A Wardrobe Workshop

Visit Greenfield Village and you can’t help but notice the clothing. From the colonial-era linen garments worn by the Daggett Farmhouse staff as they go about their daily chores to the 1920s flapper-style dresses donned by the village singers, or even the protective clothing worn by the pottery shop staff in the Liberty Craftworks district — all outfits in Greenfield Village are designed to add to the guest experience. In many cases, these tangible elements help accurately showcase the time period being interpreted.

“Clothing is such a big part of history,” said Tracy Donohue, general manager of The Henry Ford’s Clothing Studio, which creates most of The Henry Ford’s reproduction apparel and textiles for daily programs as well as seasonal events. “It’s a huge part of how we live even today. The period clothing we provide helps bring to life the stories we tell in the village and enhances the experience for our visitors.”

The Clothing Studio is tucked away on the second floor of Lovett Hall. It provides clothing for nearly 800 people a year in accurate period garments, costumes and uniforms, and covers more than 250 years of fashion — from 1760 to the present day — making the studio one of the premier museum period clothing and costume shops in the country.

The scope and flow of work in the studio is immense, from outfitting staff and presenters for the everyday to clothing hundreds for extra seasonal programs such as Historic Base Ball, Hallowe’en and Holiday Nights. Work on the April opening of Greenfield Village, for example, begins before the Holiday Nights program ends in December, with the sewing of hundreds of stock garments and accessories in preparation for hundreds of fitting sessions for new and current employees.

“When it comes to historic clothing, our goal is to create garments accurate to the period — what our research indicates people in that time and place wore,” said Donohue. “For our group, planning for Hallowe’en is an especially fun challenge. We have more creative license with costumes for this event than we typically do with our daily period clothing.”

For Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village, the studio staff researches new characters and can work on the design and development for more elaborate wearables for months. In addition to new costume creation, each year existing outfits are refreshed and/or reinvented. Last year, for example, the studio added the Queen of Hearts, Opera Clown and a number of other new characters to the Hallowe’en catalog. Plus, they freshened the look of the beloved dancing skeletons and the popular pirates.

Historic clothing, period photographs, prints, trade catalogs and magazines from the Archive of American Innovation provide a wealth of on-site resources to explore the styles, clothing construction and fabrics worn by people decades or centuries ago. Each year, Jeanine Head Miller, curator of domestic life, and Fran Faile, textile conservator, host the studio’s talented staff for a field trip to the collections storage area for an up-close look at original clothing from a variety of time periods.

“Getting the details right really matters,” Miller said. “Clothing is part of the powerful immersive experience we provide in Greenfield Village. Having people in accurate period clothing in the homes and the buildings helps our visitors understand and immerse themselves in the past, and think about how it connects to their own lives today.”

Did You Know?

The Clothing Studio has a comprehensive computerized inventory management system, which tracks close to 50,000 items.

During each night of Hallowe’en, Clothing Studio staff are on call, checking on costumed presenters throughout the evening to ensure they look their best.

What They're Wearing Under There

At Greenfield Village, costume accuracy goes well beyond what’s on the surface. Depending on the time period they’re interpreting, women may also wear chemises, corsets and stays.

“Our presenters have a lot of pride in wearing the clothing and wearing it correctly,” said Donohue.

While the undergarments function in the service of historic accuracy, corsets also provide back support and chemises help absorb sweat. Natural fibers in cotton fabrics breathe, so they’re often cooler to wear than modern-day synthetic fabrics. And when the weather runs to extreme cold conditions, layers of period-appropriate outerwear help keep village staff warm. The staff at the Clothing Studio also sometimes turns to a few of today’s tricks to keep staff comfortable. Wind- and water-resistant performance fabrications are often built into Hallowe’en costumes to offer a level of protection from outdoor elements.

“It can be 100 degrees in the summer and 10 degrees on a cold Holiday Night,” Donohue said. “Our staff is out in the elements, and they still have to look amazing. We care about the look and overall visual appearance of the outfit, of course, but we also care about the person wearing it.”

From The Henry Ford Magazine. This story originally ran in the June-December 2016 issue.

Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village, events, Greenfield Village, making, costumes, fashion, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford Magazine

Get to Know Our Digital Collections

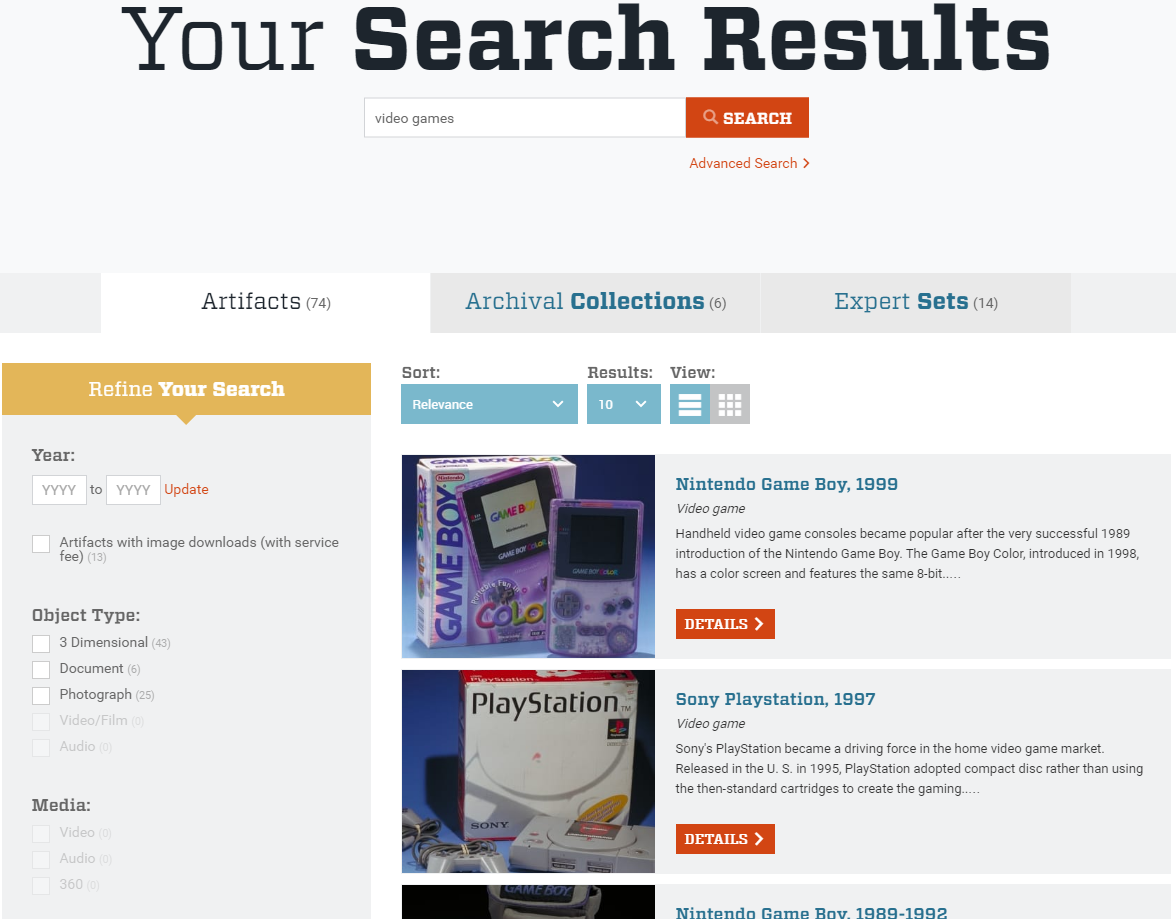

Earlier this year, The Henry Ford launched a brand-new, award-winning institutional website. Part of this project—but a big part!—is a completely reimagined Digital Collections. The Henry Ford has been scaling up its collections digitization efforts since 2010, and you’ll find tens of thousands of artifacts available online (some of the most recent additions here), with many new and enhanced features on the new site. Though we hope the new Digital Collections experience is intuitive and easy to use, we wanted to highlight some of the features for those who might not yet have had a chance to dig in and explore.

One of the best things about our Digital Collections is that they are now fully integrated with the rest of our website. This means that any search you try on our website will return results from our educational resources, our Digital Collections, and the rest of the site, in convenient tabbed format.

Digital Collections artifact results from a site search on thehenryford.org.

If you’re specifically interested in our artifacts, you can easily perform collections-specific searches from the homepage of our Digital Collections. By entering a word or phrase in the single box, you will search three kinds of records—individual artifacts, archival collections, and expert sets, with each group of results returning in its own tab. For artifacts, you can limit your search results by date, the type of artifact (objects, photos, documents, videos/film, or audio), the location of the artifact (Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, the Benson Ford Research Center, or not on exhibit), the special multimedia types available for that artifact (360-degree views, audio, or video), and whether there are high-resolution images available for automated download for a service fee. Search results can be sorted by relevance, title, or date.

Search results from a search from the homepage of our Digital Collections.

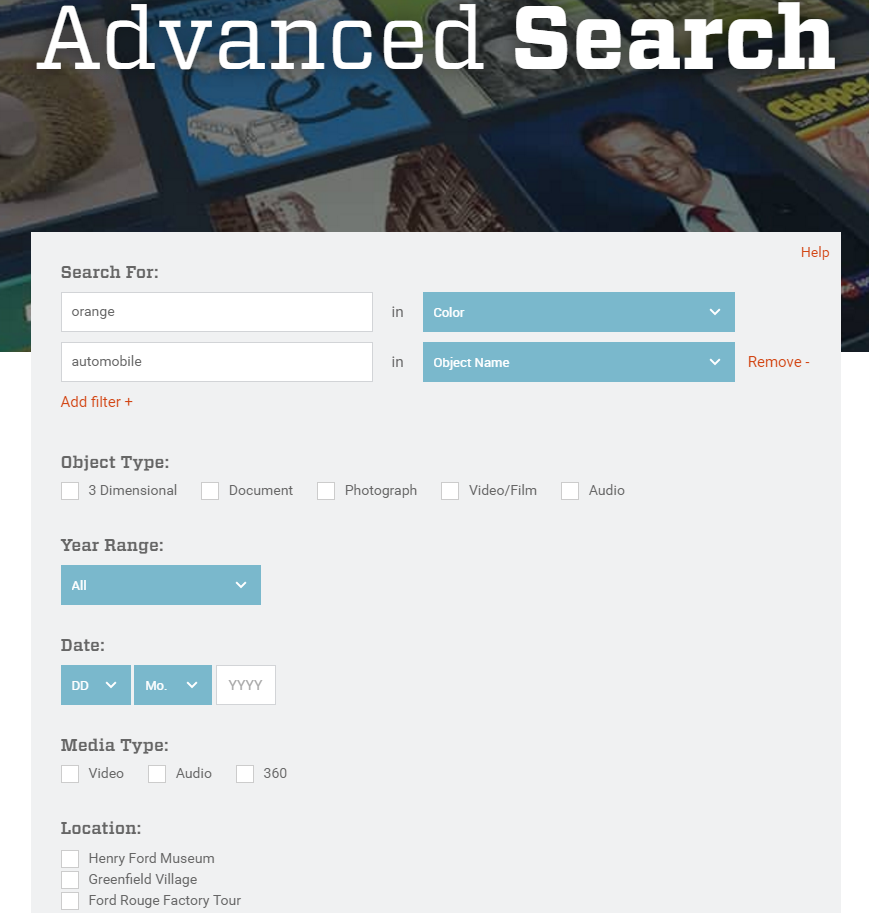

If you need to get even more detailed, you can, with one of my favorite new features on the Digital Collections site, Advanced Search. While the Digital Collections homepage search features a single box and returns results based on relevance, the more sophisticated advanced search lets you combine any of 20 different parameters, such as collection title, color, material, or creator name. Want to find orange automobiles? Or velvet dresses? Or photographs from the Fair Lane Papers collection? With Advanced Search, you can! An online help guide explains the many different fields and provides sample values for each to assist you in constructing your search.

Once you’ve found an artifact you want to check out, you’ll notice that the look of each artifact record has changed. You will now see more information about each object, and it is easier and faster to flip through the images of each object—or zoom in to see fine details. Some objects may include 360-degree views, audio, and/or video. Each record features a “contact us about this artifact” button, through which you can e-mail our collections experts in the Benson Ford Research Center to ask questions or provide additional information or corrections to our data.

The look of an artifact record in our new Digital Collections.

The look of an artifact record in our new Digital Collections.

Many Digital Collections records now display related artifacts, so while viewing something like the record for a historic photo of the Autogiro, you’ll be able to easily jump to the Autogiro itself. “Related content,” such as a story or video we’ve created including that object or other objects from our collection, will also appear where appropriate (see the record for our Apple 1 for examples). Artifacts may be shared via Facebook, Twitter, e-mail, or as “artifact cards,” short, portable versions of collections records that you can embed on your blog or website. Social sharing links and instructions for using artifact cards are available via a link on every collections record.

Archival collection records are brand-new to our Digital Collections. Previously, you needed to use our library catalog in order to find broad information about specific archival collections. Our new site allows us to include information from archival finding aids alongside the records that represent individual items from those collections. We will continue to add these archival records as collections are acquired and processed.

A record for one of our many archival collections.

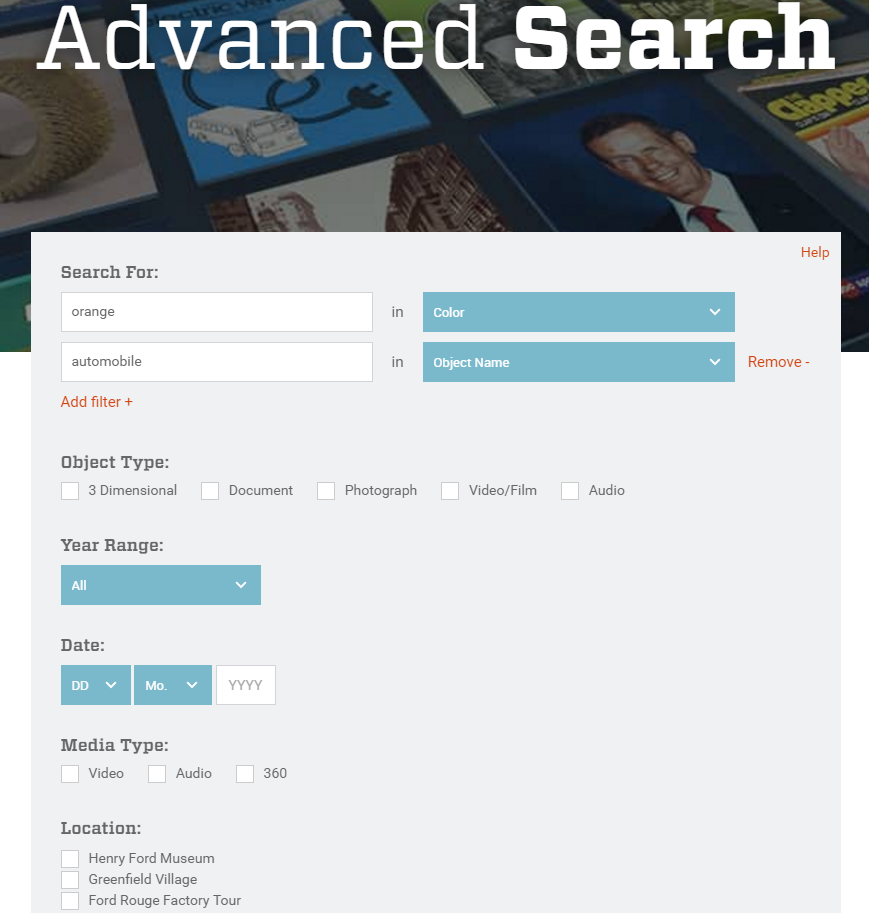

Expert sets have been totally overhauled. They still collect groups of artifacts selected by our collections experts on specific themes, but are much more robust and visually appealing. As noted above, they are also searchable directly from the Digital Collections homepage. But you don’t have to be an expert to create your own set… Anyone can! Just click the “Add to Set” button on any artifact record and log in or create an account. It is also easy to share both expert sets and user sets via Facebook, Twitter, or e-mail.

One of hundreds of artifact Expert Sets created by our collections staff.

Another notable new feature of the site is that many of our collections images are available for immediate high-resolution download for a service fee. Anywhere you see the BUY icon on an image (or use the relevant search limiter), you can purchase that image for personal or educational use in accordance with the terms of service listed on the site. We will continue to add more purchasable images to our Digital Collections over time. Lower-res images may be downloaded without a fee.

Lastly, if you ever tried to use our old Digital Collections site on a smartphone or tablet, you might have found it a frustrating experience. The new Digital Collections site is completely responsive, and all features will work equally well on your phone, tablet, or desktop computer.

Please try out our Digital Collections, if you haven't already, and feel free to contact us if you have any questions or comments about your experience. Our hope is that our new Digital Collections makes it easier and more fun for you to find, enjoy, and share the many treasures of The Henry Ford!

Ellice Engdahl is Digital Collections & Content Manager at The Henry Ford.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Ellice Engdahl, digital collections

If you’ve ever walked by the conservation labs at the back of Henry Ford museum, you’ve probably seen the conservators at work on a variety of objects, of a variety of sizes. With a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, we are primarily working on “bench-top” objects – which can be picked up and moved by hand. There are, however, a handful of extra-large objects that we have planned to work on over the course of the grant, including (but not limited to!) historically significant motors, electrostatic producers, and transformers. These objects are important within the electrical scope of the grant, and they need work to be stabilized and preserved for the future.

If you’ve ever walked by the conservation labs at the back of Henry Ford museum, you’ve probably seen the conservators at work on a variety of objects, of a variety of sizes. With a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, we are primarily working on “bench-top” objects – which can be picked up and moved by hand. There are, however, a handful of extra-large objects that we have planned to work on over the course of the grant, including (but not limited to!) historically significant motors, electrostatic producers, and transformers. These objects are important within the electrical scope of the grant, and they need work to be stabilized and preserved for the future. Note that “extra-large” for us is a lot different than extra-large for the rest of the museum – the Allegheny is magnitudes larger than anything we are working with, for example! The “extra-large” objects that we are working on range up to 2 tons in weight, and require specialized equipment such as forklifts to move. We draw the line at artifacts requiring specialist rigging or outside contractors. These sorts of objects do bring their own issues – moving them from one place to another is difficult and requires careful planning, they require a good deal of space in the lab, and the treatments can take a significant length of time. We’re moving at a quick pace with the work on this grant, so taking two to three weeks just working on one object isn’t a good solution for us.

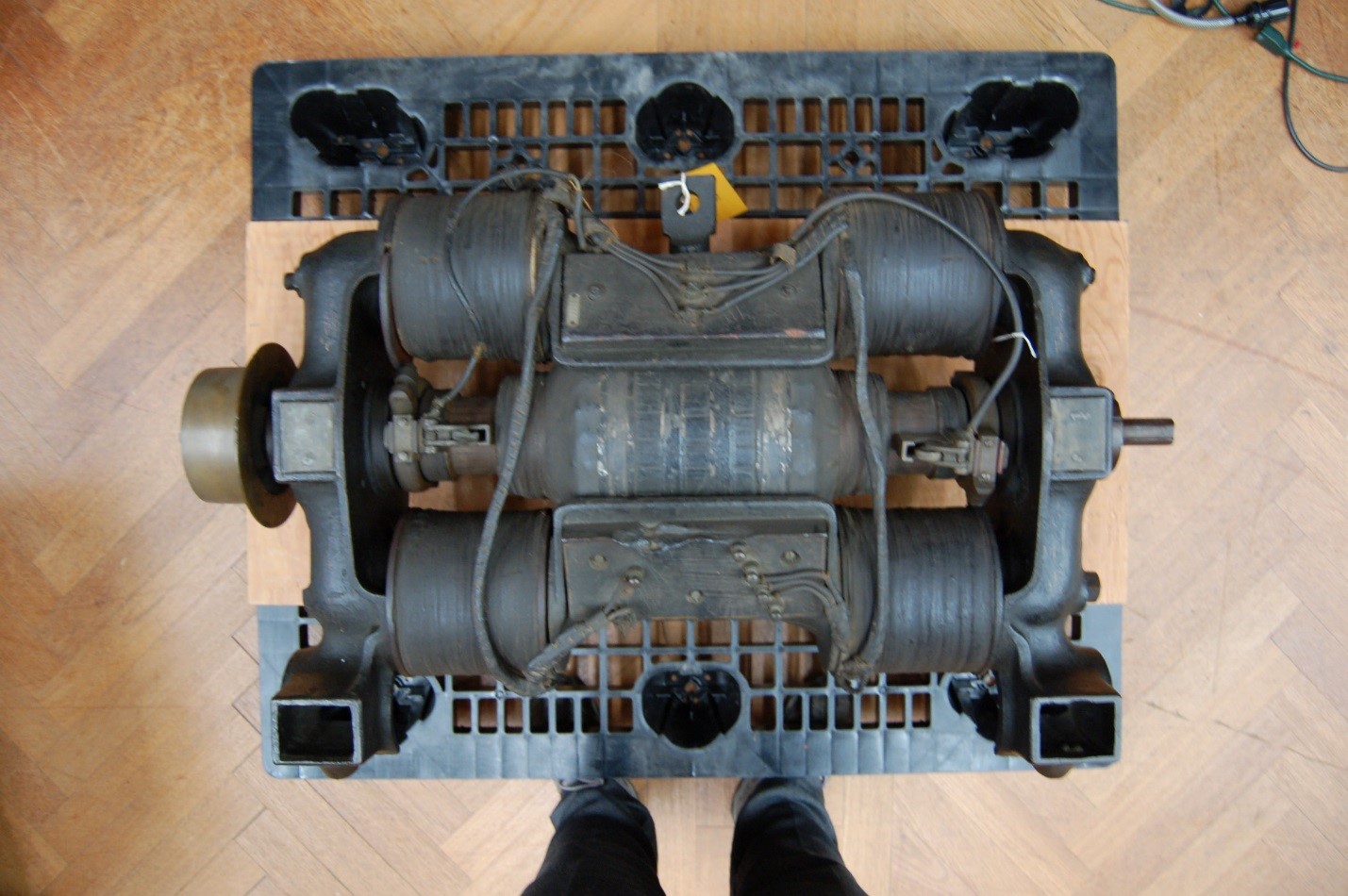

The first extra-large object we’ve grabbed, viewed top-down – a Sprague streetcar motor.

So how do we balance the amount of time it takes to treat very large objects with the need to keep up a pace in order to achieve completion goals? We’ve tackled this perennial problem in an interesting way. Since we don’t have an enormous number of extra-large objects to complete, we are allowing three months for the conservation of each. What this means practically is that we can bring the object into the lab, give it a space, and then as we have breaks between work on smaller objects, we can dedicate a few hours to it here and there. Breaking up the conservation work in this way has been very successful so far!The first object that we’ve treated in this way is a Sprague streetcar motor. This is a really interesting and important object, believed to have been used in Richmond, Virginia on the first major electric street railway system, and dating to the end of the 19th century.

Two of the coils on the motor before treatment.

In the image above are shown two of the coils on the motor before treatment – the textile covering was loose and dirty, and in some places the damage extended to the layer below the outer wrapping as well. The treatment for this object required not only cleaning, but repair to these areas of damage.

Their ‘tails’ have been rewound and reattached, and the dust and dirt have been removed. The area around the coils has also been cleaned and the wire wrappings have been tidied. The engine overall is nearing completion, but does have some areas that still need cleaning. It’s been great to have it as a project we can come back to for small spurts of time, which is exactly what we were hoping for our extra-large object treatment plan.

Louise Stewart Beck is IMLS Conservator at The Henry Ford.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, collections care, conservation, by Louise Stewart Beck, IMLS grant

Is a Conservator a Scientist?

ANSWER: According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a scientist is “a person who is trained in a science and whose job involves doing scientific research or solving scientific problems.”

Based upon this definition, I agree it would be easy to consider conservators scientists. But, truthfully, scientific work represents only a portion of the work that we carry out on a daily basis.

Conservation as a field is interdisciplinary.

It involves studio practices, sciences and the humanities. As a conservator, you are responsible for the long-term preservation of artistic and cultural artifacts. We analyze and assess the condition of cultural property and use our knowledge to develop collection care plans and site management strategies. We also carry out conservation treatments and related research.

Now, there are conservation scientists, who represent a specialized, highly trained subset of conservation professionals whose work concentrates exclusively on the science of artifact preservation. Rather than conserving artifacts, they focus their daily efforts on the analysis of artifact materials to determine how to best prevent degradation. They also conduct research to establish the best materials and techniques for conservators to use when they work on artifacts.

So are conservators scientists? No, we are not. But we do use an extensive training in material science, in combination with artistic skills and knowledge of art history, to conserve museum artifacts.

Mary Fahey is Chief Conservator at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford Magazine, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, collections care, conservation, by Mary Fahey

Garage Art

Photo by Bill Bowen.

Model T mechanics are restoration artists in their own right.

The Henry Ford has a fleet of 14 Ford Model T’s, 12 of which ride thousands of visitors along the streets of Greenfield Village every year.

With each ride, a door slams, shoes skid across the floorboards, seats are bounced on, gears are shifted, tires meet road, pedals are pushed, handles are pulled and so on. Makes maintaining the cars and preserving the visitor experience a continuous challenge.

“These cars get very harsh use,” said Ken Kennedy, antique vehicle mechanic and T Shed specialist at The Henry Ford. “Between 150,000 and 180,000 people a year ride in them. Each car gives a ride every five to seven minutes, with the longest route just short of a mile. This happens for nine months a year.”

The T Shed is the 3,600-square-foot garage on the grounds of Greenfield Village where repairs, restoration and maintenance magic happen. Kennedy, who holds a degree in restoration from McPherson College in Kansas, leads the shed’s team of staff and volunteers — many car-restoration hobbyists just like him.

“I basically turned my hobby into a career,” quipped Kennedy, who began restoring cars long before college. His first project: a 1926 two-door Model T sedan. “I also have a 1916 Touring and a 1927 Willys-Knight. And I’m working on a Model TT truck,” he added.

April through December, the shed is humming, doing routine maintenance and repairs on the Model T’s as well as a few Model AA trucks that round out Greenfield Village’s working fleet. “What the public does to these cars would make any hobbyist pull their hair out. Doors opening and shutting with each ride. Kids sliding across the seats wearing on the upholstery,” said Kennedy. Vehicles often go through a set of tires every year. Most hobbyist-owned Model T’s have the same set for three-plus decades.

With the heavy toll taken on the vehicles, the T Shed’s staff often makes small, yet important, mechanical changes to the cars to ensure they can keep up. “We have some subtle things we can do to make them work better for our purpose,” said Kennedy. Gear ratios, for example, are adjusted since the cars run slow — the speed limit in Greenfield Village is 15 miles per hour, maximum. “The cars look right for the period, but these are the things we can do to make our lives easier.”

In the off-season, when Greenfield Village is closed, the T Shedders shift toward more heavy mechanical work, replacing upholstery tops and fenders, and tearing down and rebuilding engines. While Kennedy may downplay the restoration, even the conservation, underpinnings of the work happening in the shed, the mindset and philosophy are certainly ever present.

“Most of the time we’re not really restoring, but you still have to keep in mind authenticity and what should be,” he said. “It’s not just about what will work. You have to keep the correctness. We can do some things that aren’t seen, where you can adjust. But where it’s visible, we have to maintain what’s period correct. We want to keep the engines sounding right, looking right.”

Photo by Bill Bowen.

RESTORATION IN THE ROUND

Tom Fisher, Greenfield Village’s chief mechanical officer, has been restoring and maintaining The Henry Ford’s steam locomotives since 1988. “It was a temporary fill-in; I thought I’d try it,” Fisher said of joining The Henry Ford team 28 years ago while earning an engineering degree.

He now oversees a staff with similarly circuitous routes — some with degrees in history, some in engineering, some with no degree at all. Most can both engineer a steam-engine train and repair one on-site in Greenfield Village’s roundhouse.

“As a group, we’re very well rounded,” said Fisher. “One of the guys is a genius with gas engines — our switcher has a gas engine, so I was happy to get him. One guy is good with air brake systems. We feel them out, see where they’re good and then push them toward that.”

Fisher’s team’s most significant restoration effort: the Detroit & Lima Northern No. 7. Henry Ford’s personal favorite, this locomotive was formerly in Henry Ford Museum and took nearly 20 years to get back on the track.

“We had to put on our ‘way-back’ hats and say this is what we think they would have done,” said Fisher.

No. 7 is one of three steam locomotives running in Greenfield Village. As with the Model T’s, maintaining these machines is a balance between preserving historical integrity and modernizing out of necessity.

“A steam locomotive is constantly trying to destroy itself,” Fisher said. “It wears its parts all out in the open. The daily firing of the boiler induces stresses into the metal. There’s a constant renewal of parts.”

Parts that Fisher and his team painstakingly fabricate, cast and fit with their sturdy hands right at the roundhouse.

DID YOU KNOW?

The No. 7 locomotive began operation in Greenfield Village to help commemorate Henry Ford’s 150th birthday in 2013.

Additional Readings:

- Ingersoll-Rand Number 90 Diesel-Electric Locomotive, 1926

- Keeping the Roundhouse Running

- Model Train Layout: Demonstration

- Part Two: Number 7 is On Track

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, trains, The Henry Ford Magazine, railroads, Model Ts, Greenfield Village, Ford Motor Company, engineering, collections care, cars, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

The Bogus Brewster Chair

When an article was published in 1977 about a sculptor who had built a certain armchair in the 1960s — not to make a fake, but to make a point about his skill and ability to fool the experts — The Henry Ford took note. The throne-like chair described in the story was uncannily similar in every way to a 17th-century piece The Henry Ford had acquired in 1970 as a highly prized and rare Brewster, a type of chair associated with William Brewster, one of the founders of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Conservation science and strong detective work did prove the chair to be a fake, and The Henry Ford admitted to being fooled. Always an institution dedicated to education, The Henry Ford didn’t remove the chair, instead keeping it as a reminder of a lesson learned and even loaning it out for national exhibits on fakes and forgeries.

An X-ray of The Henry Ford’s Brewster chair forgery showed that the drill bits used for making the holes that received the turned spindles had a modern-day pointed end rather than the spoon shape associated with bits common to carpentry in the 1600s.

DID YOU KNOW?

William Brewster was one of 102 passengers who traveled across the Atlantic on the Mayflower in 1620 to establish Plymouth Colony.

Chairs were rare in 17th-century American homes. Chairs like the Brewster were made for honored guests or the head of the household — intended to impress visitors and confirm the sitter’s status and position. And they were not very comfortable.

The Henry Ford Magazine, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, decorative arts, furnishings

Conservation specialist Mallory Bower and collections specialist Jake Hildebrandt removing objects from shelving in the Collections Storage Building. The Henry Ford has recently embarked on a new adventure, thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) which allows us to spend time working on the electrical collections currently housed in the Collections Storage Building. This is The Henry Ford’s second IMLS grant dedicated to improving the storage of and access to collections. The first grant focused on communications technology, and was completed over two years, ending in October 2015. At the end of that grant, more than 1000 communications-related objects were conserved, catalogued, digitized, and stored, marking a huge improvement in the state of the collections and their accessibility. We have similar goals for this grant, as we aim to complete 900+ objects by October 2017.

The Henry Ford has recently embarked on a new adventure, thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) which allows us to spend time working on the electrical collections currently housed in the Collections Storage Building. This is The Henry Ford’s second IMLS grant dedicated to improving the storage of and access to collections. The first grant focused on communications technology, and was completed over two years, ending in October 2015. At the end of that grant, more than 1000 communications-related objects were conserved, catalogued, digitized, and stored, marking a huge improvement in the state of the collections and their accessibility. We have similar goals for this grant, as we aim to complete 900+ objects by October 2017.

digitization, electricity, power, by Louise Stewart Beck, conservation, collections care, IMLS grant, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford