Posts Tagged #behind the scenes @ the henry ford

"The Busy World" Automaton

“The Busy World” automaton, 1830–1850. / THF187282

“The Busy World” automaton, 1830–1850. / THF187282

I was about nine years old when I first saw it. My family and I were visiting Henry Ford Museum when I spotted “The Busy World”—an intriguingly detailed and well-populated automaton displayed along the museum’s Street of Shops displays. I was entranced. “The Busy World” would remain among my most vivid memories of this visit. Little did I know that many years later I would be involved in further research on this fascinating, whimsical object.

An automaton is a non-electric moving machine that performs a predetermined set of operations. With approximately 300 moving figures, “The Busy World” automaton is a kind of mechanized diorama with six individual platforms powered by gears, belts, and pulleys. When the automaton is cranked, the figures go into motion.

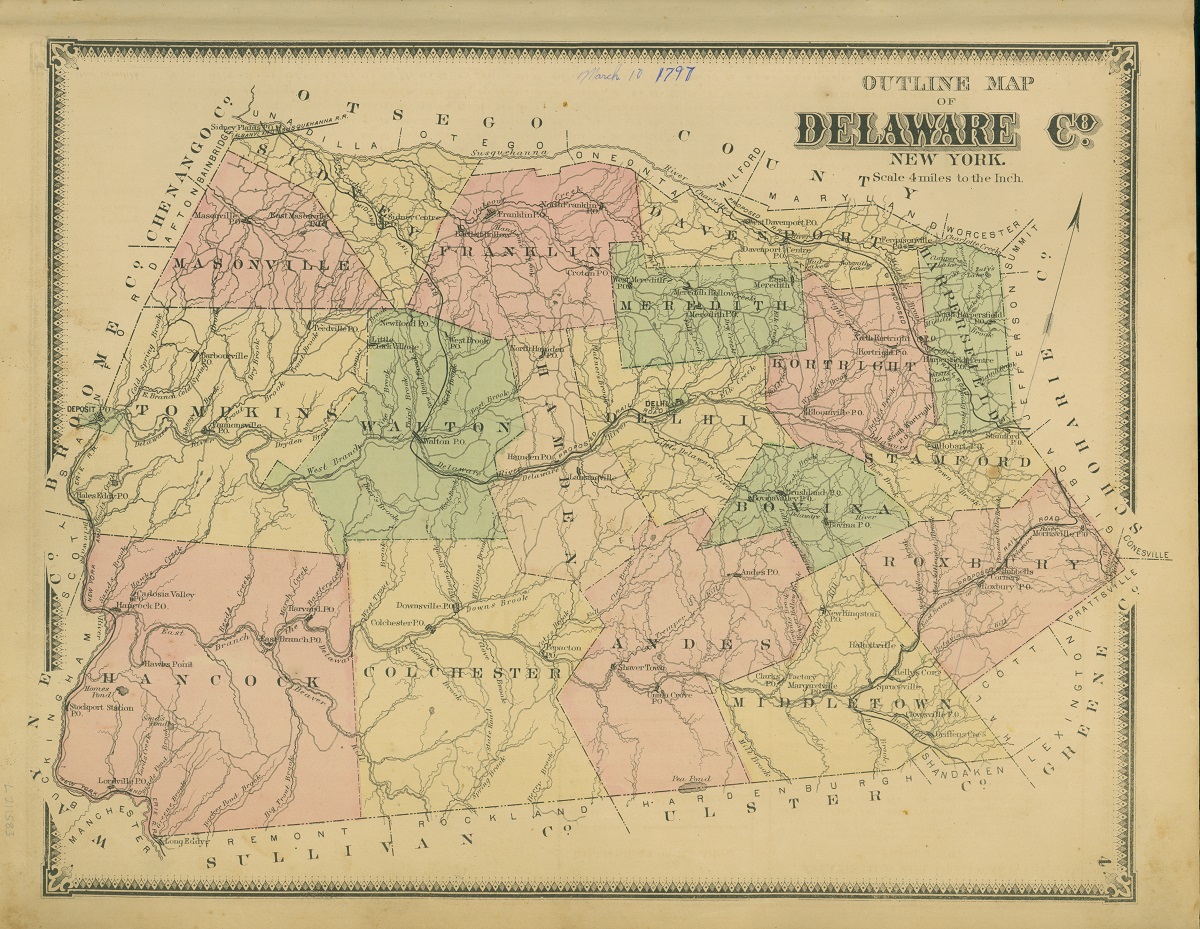

1869 Beers Atlas map of Delaware County, New York. / Image courtesy of the Delaware County Historical Association

Delaware County in upstate New York—where “The Busy World” was likely built and spent much of its working life—was a place of farms and small villages during the 19th century. The wagon's lively, hand-cranked animations would have had tremendous popular appeal for adults and children alike at country fairs and small exhibitions.

“The Busy World” features six different animated scenes. Click on the links under the scenes below to see those images in our Digital Collections, where you can zoom in on the details.

Left section of “The Busy World.” / THF187276, detail

At the upper left, figures perform activities of everyday life, including rocking a baby, getting warm by the stove, chopping food, spinning thread, churning butter, and sharpening a tool.

In the scene at lower left, people attend a ballroom dance while musicians play. At the left of the dance scene are caricatured figures of African Americans. This “Busy World” scene reflects not only the activities of the time period but also the racism of the era.

Center section of “The Busy World.” / THF187277, detail

The scene at upper center shows men making rakes and grain cradles in a factory. Delaware County had at least one rake factory. During the early 19th century, New York was the grain belt of the United States. Wooden rakes were essential tools on farms.

Biblical scene from “The Busy World.” / THF125152

At lower center, a small revolving “stage” features eight Biblical stories.

Right section of “The Busy World.” / THF187278, detail

At upper right, soldiers in uniform promenade with ladies.

The scene at lower right features a regiment of soldiers parading in formation to the “sounds” of a military band.

“The Busy World” Comes to The Henry Ford

“The Busy World” came to The Henry Ford in 1963. The museum purchased the automaton from Janos and Mary Williams of Stone Henge Antiques in Sidney, New York. Where was it before that? Well, we know part of the story.

The Williamses had acquired “The Busy World” from a man named David Smith. About 1944, David Smith (1923–2002) saw an ad in a Walton, New York, newspaper offering “The Busy World” for sale: “Will sell cheap, if sold this week, ONE busy world.” Twenty-one-year-old Smith, who lived in nearby Delhi, New York, couldn’t resist. He drove the 17 miles to Walton to take a look. Amazed and delighted with what he saw, Smith purchased the automaton with his own savings, over the objections of his family. For the first seven years that he owned it, Smith stored “The Busy World” in his family’s barn in Delhi. David Smith got it to run, at least sporadically.

It wasn’t until September 1951 that “The Busy World” once again had a public showing. David Smith’s mother had offered the family barn to the Delaware County Horticultural Society as a place to hold their annual Harvest Show. “The Busy World” delighted local people who came to see the choice vegetables, flower arrangements, and potted plants on display there. Some of those attending recalled 30 or so years before when the automaton had appeared at county fairs in the area.

Next stop for “The Busy World”? David Smith opened an antique store in his hometown of Delhi, where he displayed the automaton. The name of the shop? Busy World Antiques.

David Hoy Takes “The Busy World” on the Road

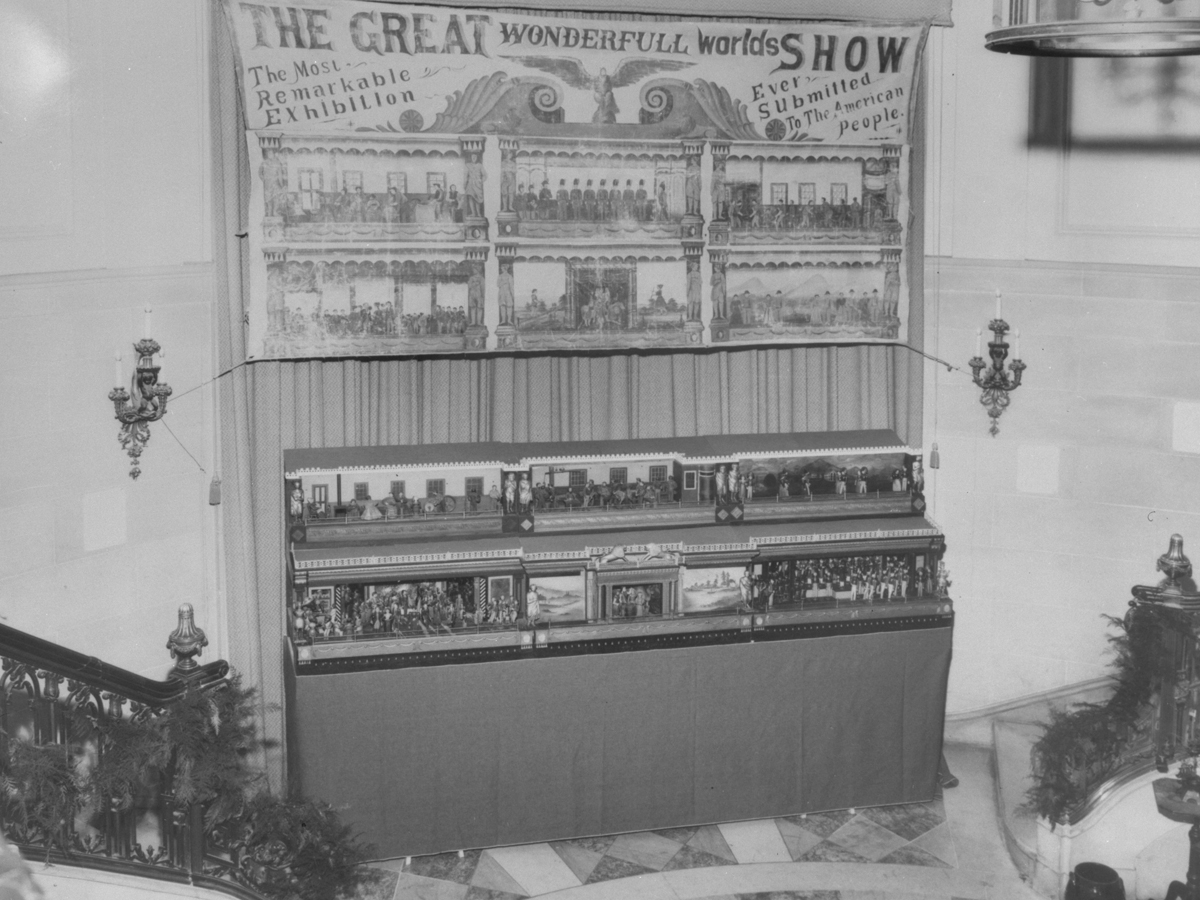

“The Busy World” platforms exhibited in an unidentified location, probably in the early 20th century. An advertising banner hangs above—one that may date from the late 1860s or 1870s. / THF125153

David Smith had purchased “The Busy World” from Elizabeth Hoy Thomas (1874–1949). She was the daughter of David Hoy (1848–1934), the man who exhibited “The Busy World” at local fairs and carnivals at the turn of the 20th century. According to David Smith, Elizabeth Hoy Thomas told him that “The Busy World” took 17 years to build and was constructed by two men—one carved the figures and the other assembled the machinery.

David Hoy’s 1934 obituary recalled Hoy’s yearly exhibitions of the “World at Work” or “Busy World” automaton at local fairs. Hoy is said to have charged five or ten cents to see “The Busy World” in motion. David Hoy exhibited “The Busy World” regularly until the mid-1910s, and then for one last time at the Walton Armory in late 1933. After his death the following year, the automaton remained in a shed at Hoy’s daughter’s home in Walton. She placed the newspaper ad offering it for sale about ten years later—the ad seen by young David Smith.

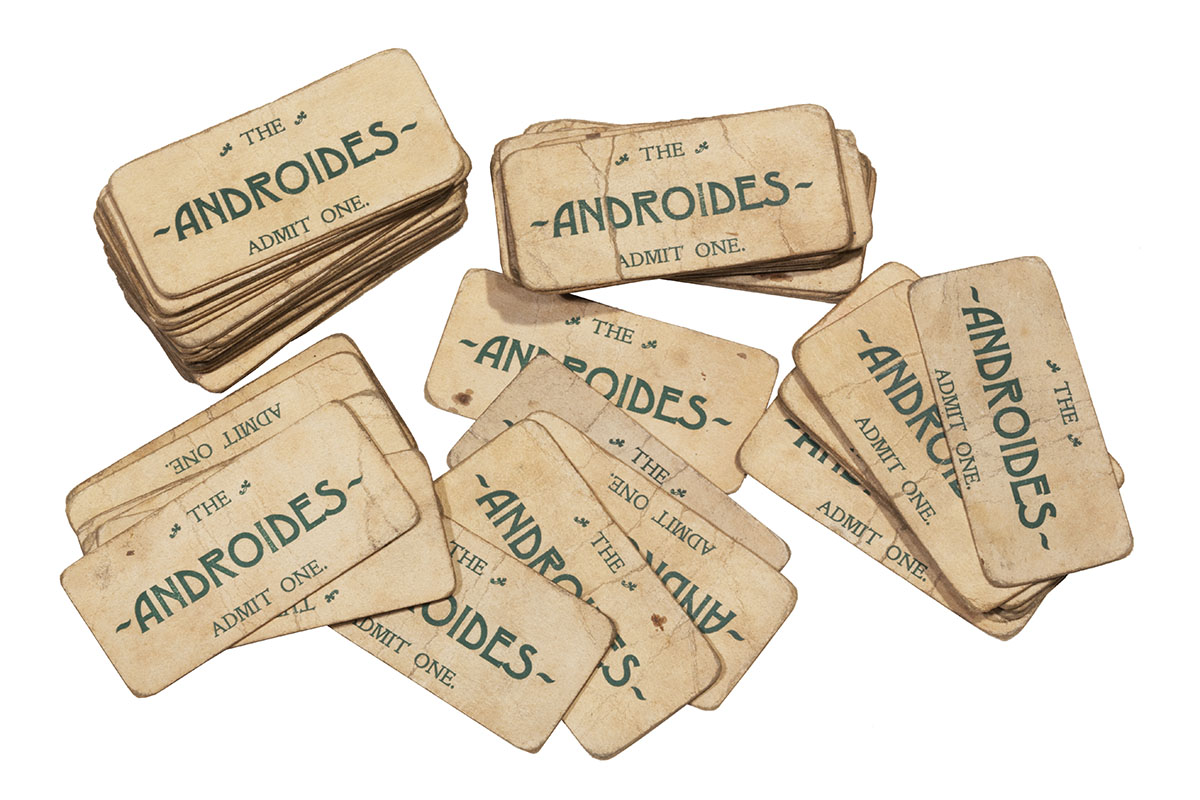

These tickets were found in the wagon. They appear to date between 1890 and 1910 and may have been used as “The Busy World” made the rounds of country fairs and carnivals in the latter portion of its career. In Latin, androides means “resembling a man,” and was used during the 19th century to describe an automaton resembling a human being in form and movement. / THF187284

Looking for Answers

We had many unanswered questions about “The Busy World.”

Curatorial research volunteer Gil Gallagher worked many months to dig up some answers, trolling census records and countless newspapers online. Ray LaFever, archivist at the Delaware County Historical Association, lent his research skills and familiarity with Delaware County history to the quest. Here’s what their research turned up.

When they sold it, antique dealers Janos and Mary Williams mistakenly told The Henry Ford that “The Busy World” had been built by David Hoy. And that he “began it in 1830 and took 17 years to make it.” As we found, not quite so—at least the part about David Hoy. Our research showed that Hoy didn’t build it. He acquired the automaton sometime later.

The general dates given for the construction of “The Busy World” appear to be correct. The figures and objects shown in the scenes reflect the era of the 1830s—including the women’s fashions, the Franklin heating stove (upper left section), and the serpent, a musical instrument (lower right section).

Therefore, David Hoy couldn’t have made it. Hoy was born in Bovina in Delaware County—but not until 1848. His family moved to Iowa when he was ten. By the mid-1870s, Hoy returned to Delaware County, where he married and had three children. During the following decades, he would make his living as a farmer, carpenter, stone mason, and teamster. Hoy must have acquired “The Busy World” sometime after he returned to Delaware County as an adult. (A 1905 newspaper article noted that the automaton was “now run by a Walton man, David Hoy,” so someone else probably toured it before Hoy.) The wagon that now carries “The Busy World” was a later addition—one likely added by Hoy, who mounted the automaton figures and machinery in the wagon to make it easier to transport. (One newspaper article mentions that the automaton platforms were originally displayed in a tent.)

So, we found some answers—yet questions remain.

Was the automaton originally called “The Busy World”? It seems that it may have acquired that title in the late-19th or early-20th century, since it is not mentioned on the banner or tickets.

And, despite all our efforts, the identities of the original makers of “The Busy World”—whoever these talented individuals were—remain a mystery for now.

Jeanine Head Miller is Curator of Domestic Life at The Henry Ford. Many thanks to Sophia Kloc, Office Administrator for Historical Resources at The Henry Ford, for editorial preparation assistance with this post.

20th century, New York, 19th century, research, popular culture, making, by Jeanine Head Miller, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

What Have We Been Collecting at The Henry Ford?: A Peek at Recent Acquisitions

The Henry Ford’s curatorial team works on many, many tasks over the course of a year, but perhaps nothing is as important as the task of building The Henry Ford’s collections. Whether it’s a gift or a purchase, each new acquisition adds something unique. What follows is just a small sampling of recent collecting work undertaken by our curators in 2021 (and a couple in 2020), which they shared during a #THFCuratorChat session on Twitter.

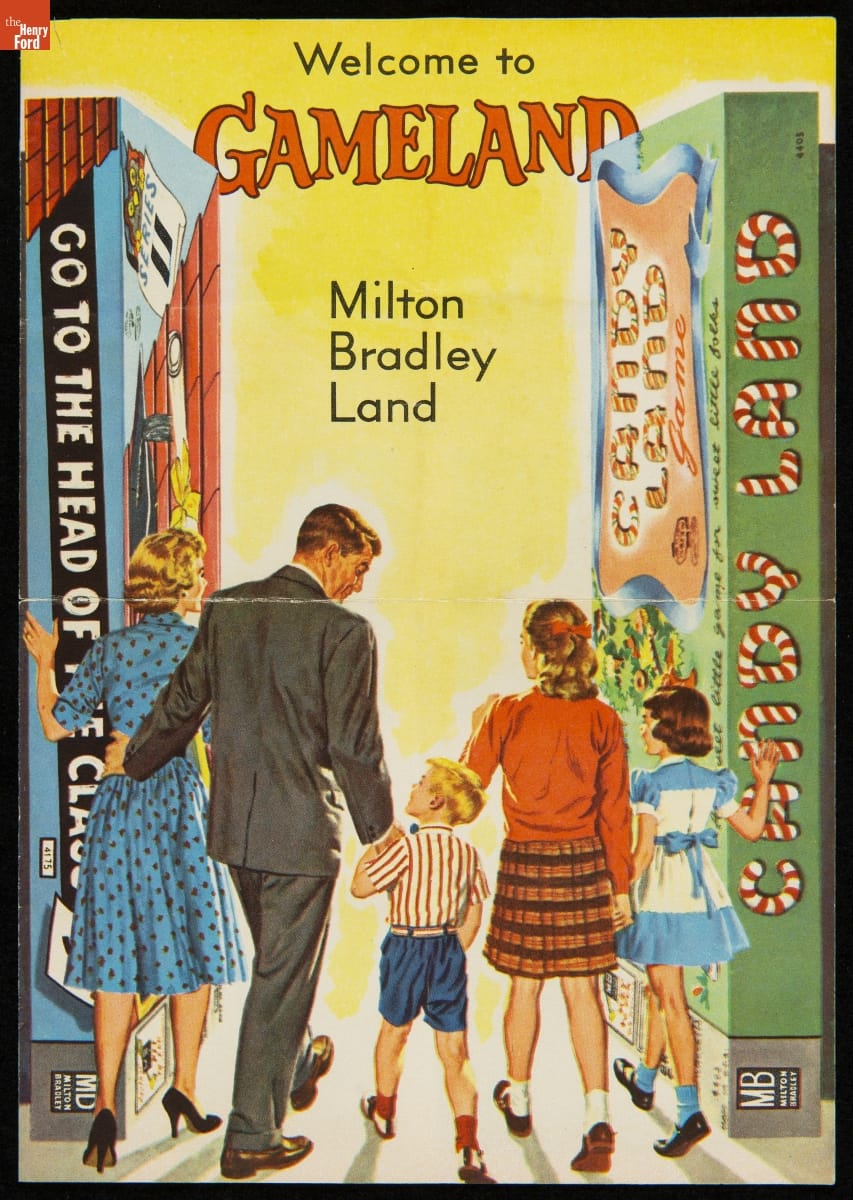

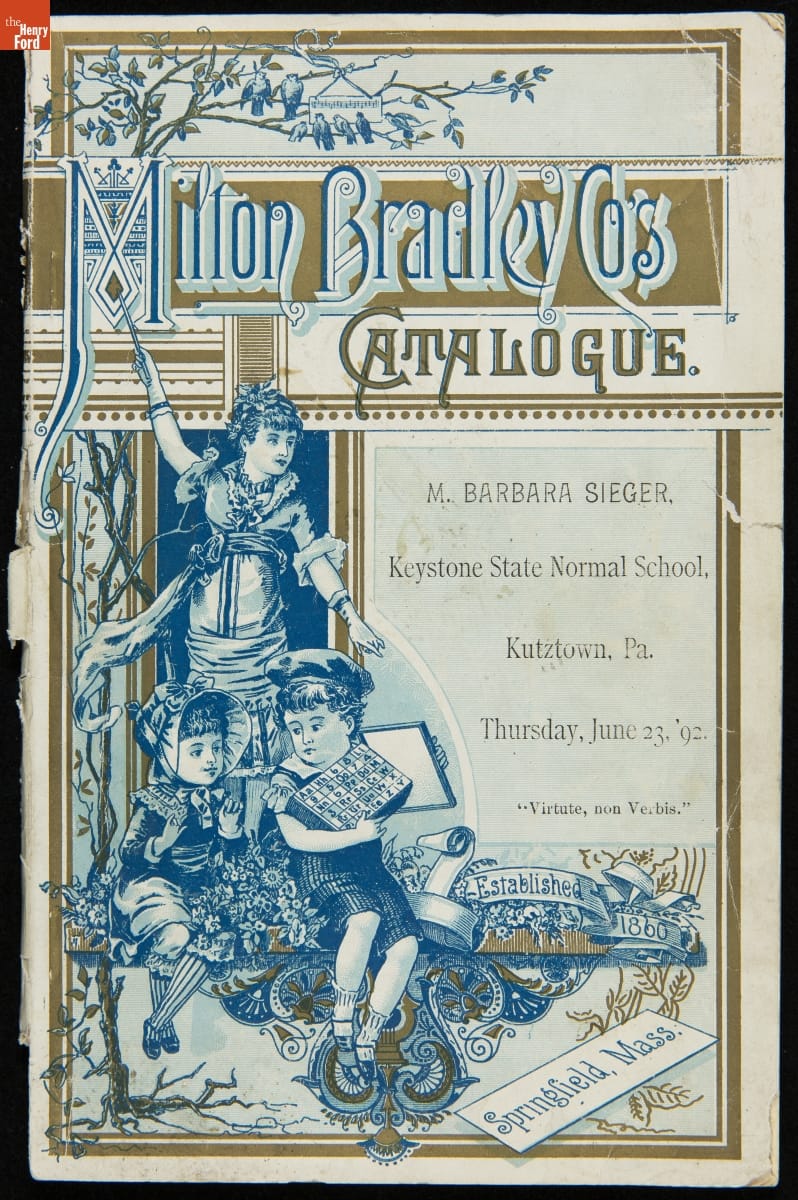

In preparation for an upcoming episode of The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation, Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller made several new acquisitions related to board games. A colorful “Welcome to Gameland” catalog advertises the range of board games offered by Milton Bradley Company in 1964, and joins the 1892 Milton Bradley catalog—dedicated to educational “School Aids and Kindergarten Material”—already in our collection.

Milton Bradley Company Catalog, “Welcome to Gameland,” 1964. / THF626388

Milton Bradley Company Trade Catalog, “Bradley’s School Aids and Kindergarten Material,” 1892. / THF626712

We also acquired several more board games for the collection, including “The Game of Life”—a 1960 creation to celebrate Milton Bradley’s centennial anniversary that paid homage to their 1860 “The Checkered Game of Life” and featured an innovative, three-dimensional board with an integrated spinner. “The Game of Life,” as well as other board games in our collection, can be found in our Digital Collections.

Board games recently acquired for use in The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation. / THF188740, THF188741, THF188743, THF188750

This year, Katherine White, Associate Curator, Digital Content, was thrilled to unearth more of the story of designer Peggy Ann Mack. Peggy Ann Mack is often noted for completing the "delineation" (or illustration) for two early 1940s Herman Miller pamphlets featuring her husband Gilbert Rohde's furniture line. After Rohde's death in 1944, Mack took over his office. One commission she received was to design interiors and radio cases for Templetone Radio. The Henry Ford recently acquired this 1945 radio that she designed.

Radio designed by Peggy Ann Mack, 1945. / Photo courtesy Rachel Yerke

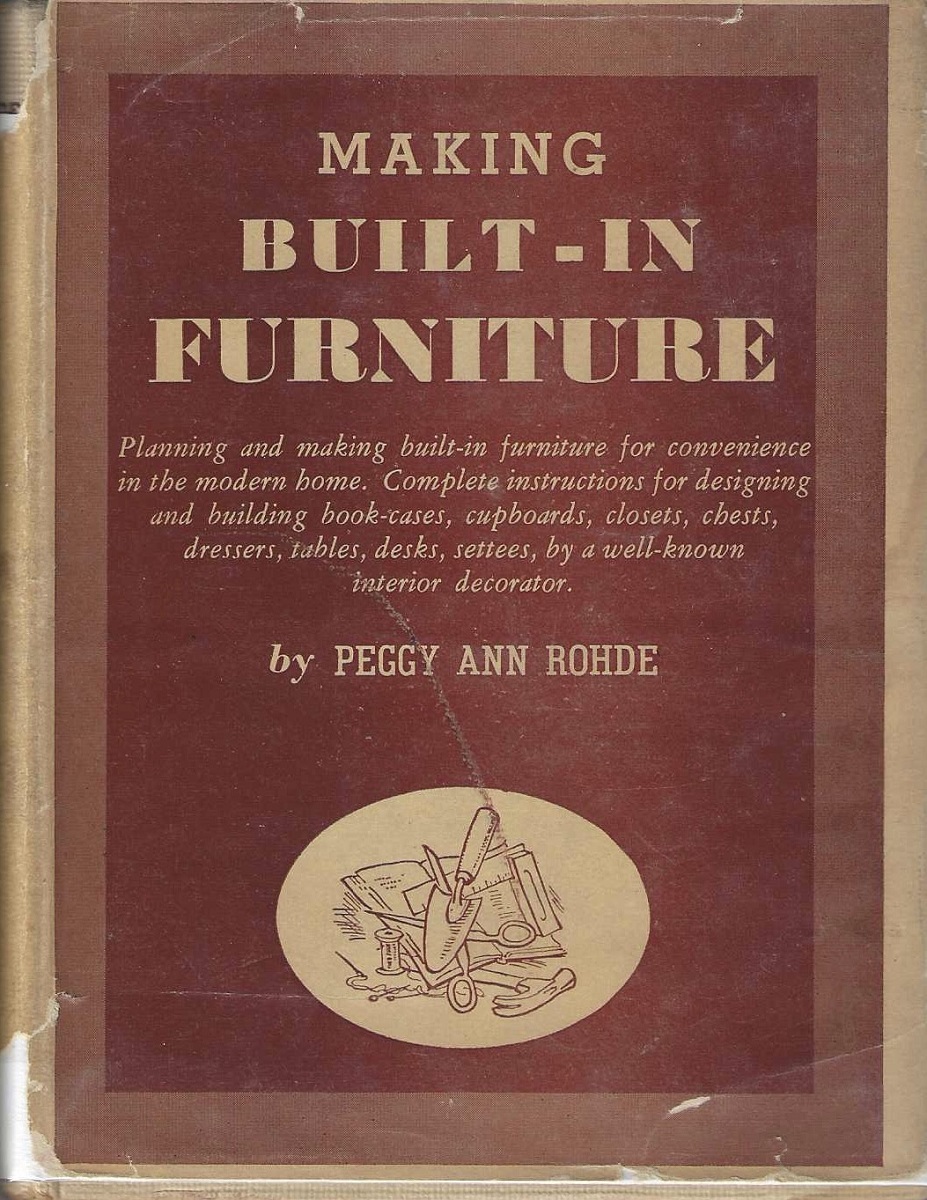

Peggy Ann Mack wrote and illustrated the book Making Built-In Furniture, published in 1950, which The Henry Ford also acquired this year. The book is filled with her illustrations and evidences her deep knowledge of the furniture and design industries.

Making Built-In Furniture, 1950. / Photo courtesy Katherine White

Mack (like many early female designers) has never received her due credit. While headway has been made this year, further research and acquisitions will continue to illuminate her story and insert her name back into design history.

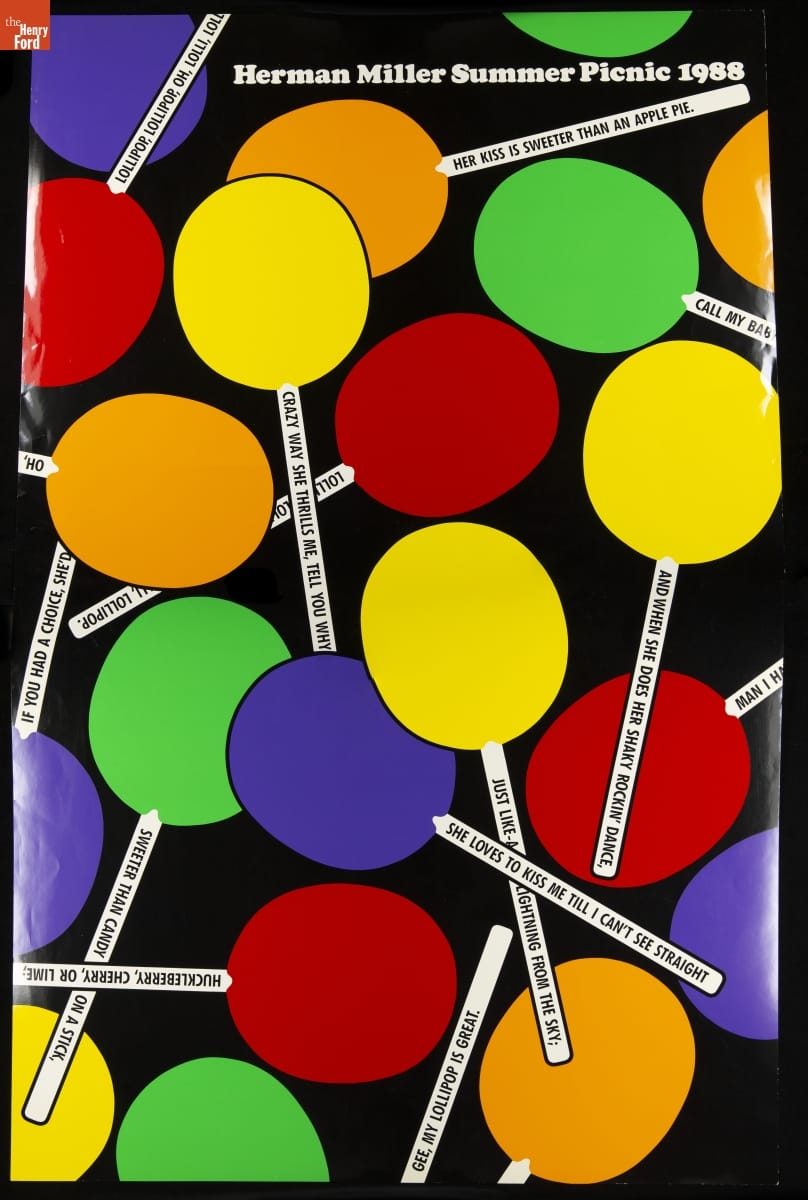

Katherine White also worked this year to further expand our collection of Herman Miller posters created for Herman Miller’s annual employee picnic. The first picnic poster was created by Steve Frykholm in 1970—his first assignment as the company’s internal graphic designer. Frykholm would go on to design 20 of these posters, 18 of which were acquired by The Henry Ford in 1988; this year, we finally acquired the two needed to complete the series.

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Lollipop,” 1988. / THF626898

Herman Miller Summer Picnic Poster, “Peach Sundae,” 1989. / THF189131

After Steve Frykholm, Kathy Stanton—a graduate of the University of Cincinnati’s graphic design program—took over the creation of the picnic posters, creating ten from 1990–2000. While The Henry Ford had one of these posters, this year we again completed a set by acquiring the other nine.

Recently acquired posters created by Kathy Stanton for Herman Miller picnics, 1990–2000 / THF626913, THF626915, THF626917, THF626921, THF189132, THF189133, THF189134, THF626929, THF626931

Along with the picnic posters, The Henry Ford also acquired a series of posters for Herman Miller’s Christmas party; these posters were created from 1976–1979 by Linda Powell, who worked under Steve Frykholm at Herman Miller for 15 years. All of these posters—for the picnics and the Christmas parties—were gifted to us by Herman Miller, and you can check them out in our Digital Collections.

Posters designed by Linda Powell for Herman Miller Christmas parties, 1976–1979 / THF626900, THF189135, THF189137, THF189136, THF189138, THF626909, THF626905

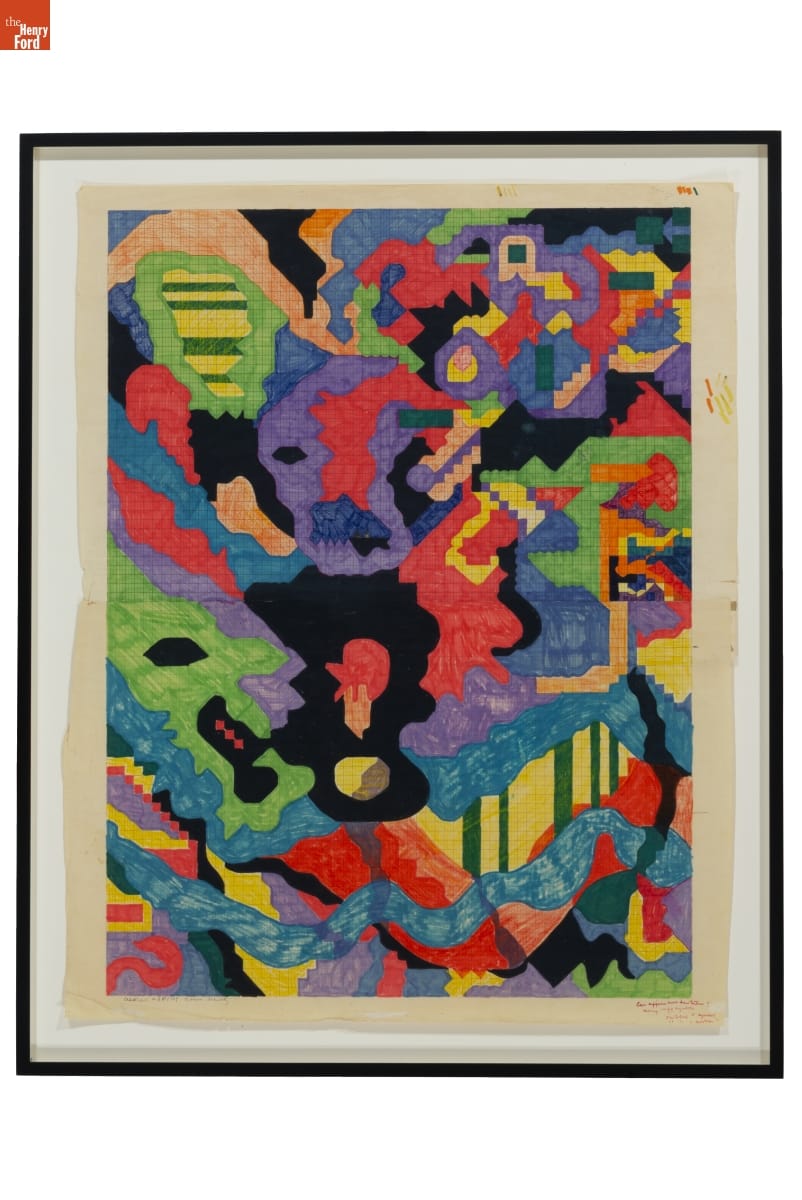

Thanks to the work of Curator of Communications and Information Technology Kristen Gallerneaux, in early 2021, a very exciting acquisition arrived at The Henry Ford: the Lillian F. Schwartz and Laurens R. Schwartz Collection. Lillian Schwartz is a groundbreaking and award-winning multimedia artist known for her experiments in film and video.

Lillian Schwartz was a long-term “resident advisor” at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey. There, she gained access to powerful computers and opportunities for collaboration with scientists and researchers (like Leon Harmon). Schwartz’s first film, Pixillation (1970), was commissioned by Bell Labs. It weaves together the aesthetics of coded textures with organic, hand-painted animation. The soundtrack was composed by Gershon Kingsley on a Moog synthesizer.

“Pixillation, 1970 / THF611033

Complementary to Lillian Schwartz’s legacy in experimental motion graphics is a large collection of two-dimensional and three-dimensional materials. Many of her drawings and prints reference the creative possibilities and expressive limitations of computer screen pixels.

“Abstract #8” by Lillian F. Schwartz, 1969 / THF188551

With this acquisition, we also received a selection of equipment used by Lillian Schwartz to create her artwork. The equipment spans from analog film editing devices into digital era devices—including one of the last home computers she used to create video and still images.

Editing equipment used by Lillian Schwartz. / Image courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

Altogether, the Schwartz collection includes over 5,000 objects documenting her expansive and inquisitive mindset: films, videos, prints, paintings, sculptures, posters, and personal papers. You can find more of Lillian Schwartz’s work by checking out recently digitized pieces here, and dig deeper into her story here.

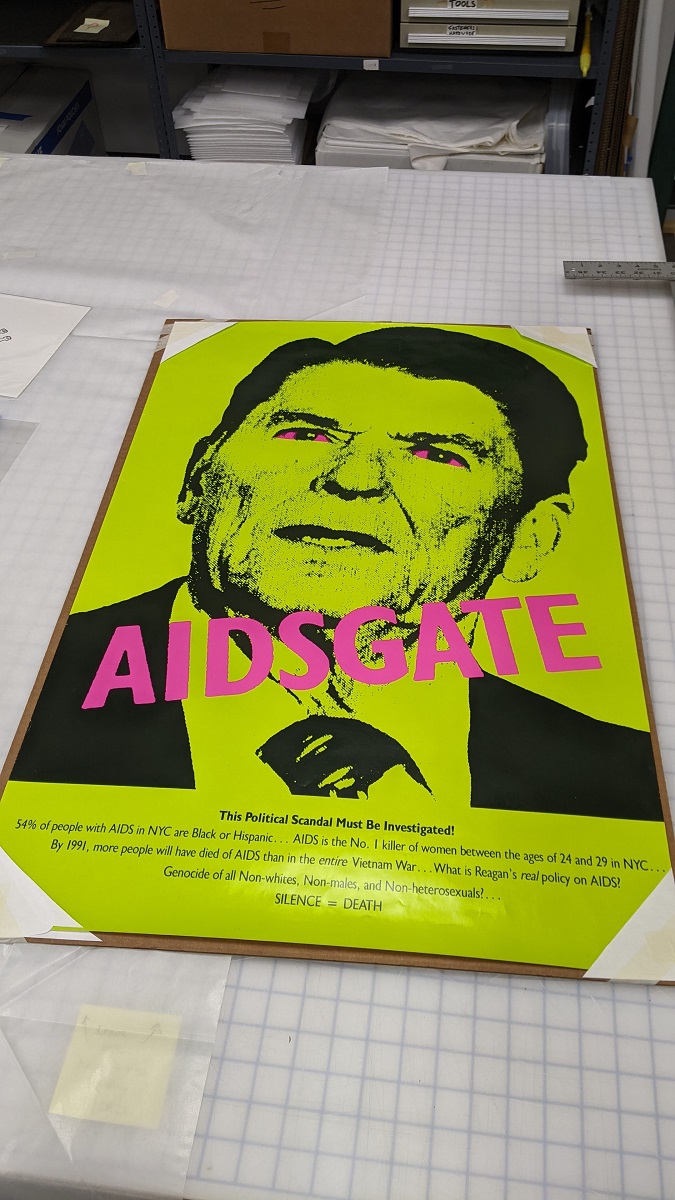

Katherine White and Kristen Gallerneaux worked together this year to acquire several key examples of LGBTQ+ graphic design and material culture. The collection, which is currently being digitized, includes:

Illustrations by Howard Cruse, an underground comix artist…

Illustration created by Howard Cruse. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

A flier from the High Tech Gays, a nonpartisan social club founded in Silicon Valley in 1983 to support LGBTQ+ people seeking fair treatment in the workplace, as LGBTQ+ people were often denied security clearance to work in military and tech industry positions...

High Tech Gays flier. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

An AIDSGATE poster, created by the Silence = Death Collective for a 1987 protest at the White House, designed to bring attention to President Ronald Reagan’s refusal to publicly acknowledge the AIDS crisis...

“AIDSGATE” Poster, 1987. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

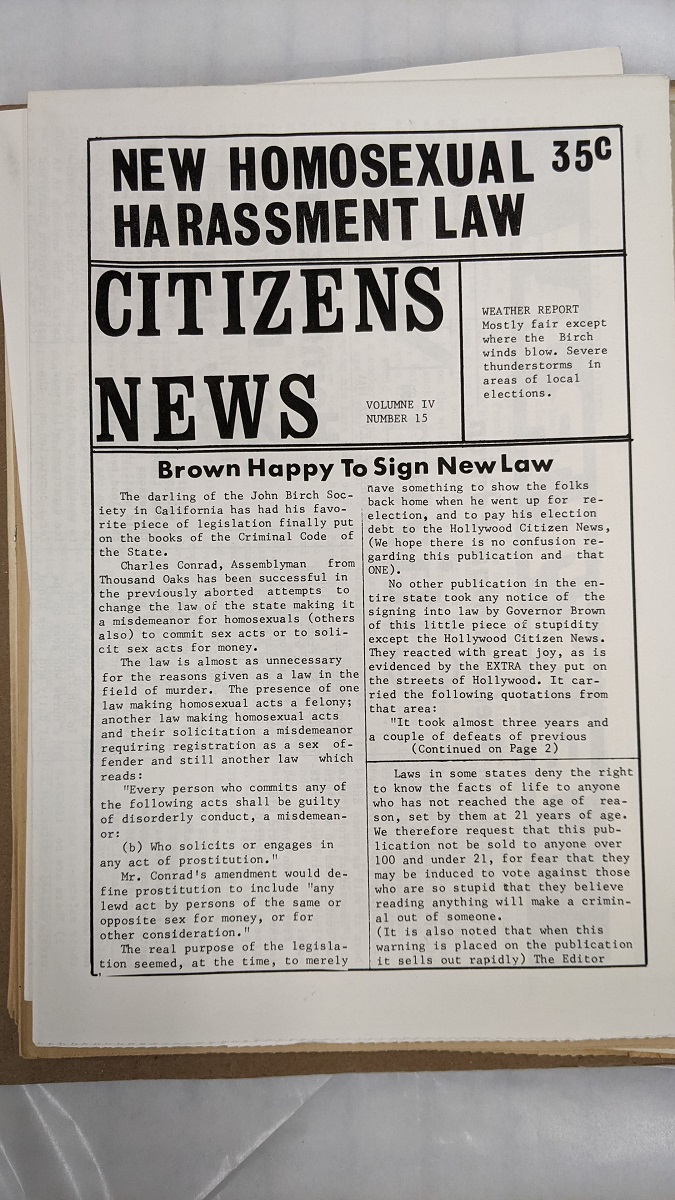

A number of mid-1960s newspapers—typically distributed in gay bars—that rallied the LGBTQ+ community, shared information, and united people under the cause...

“Citizens News.” / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

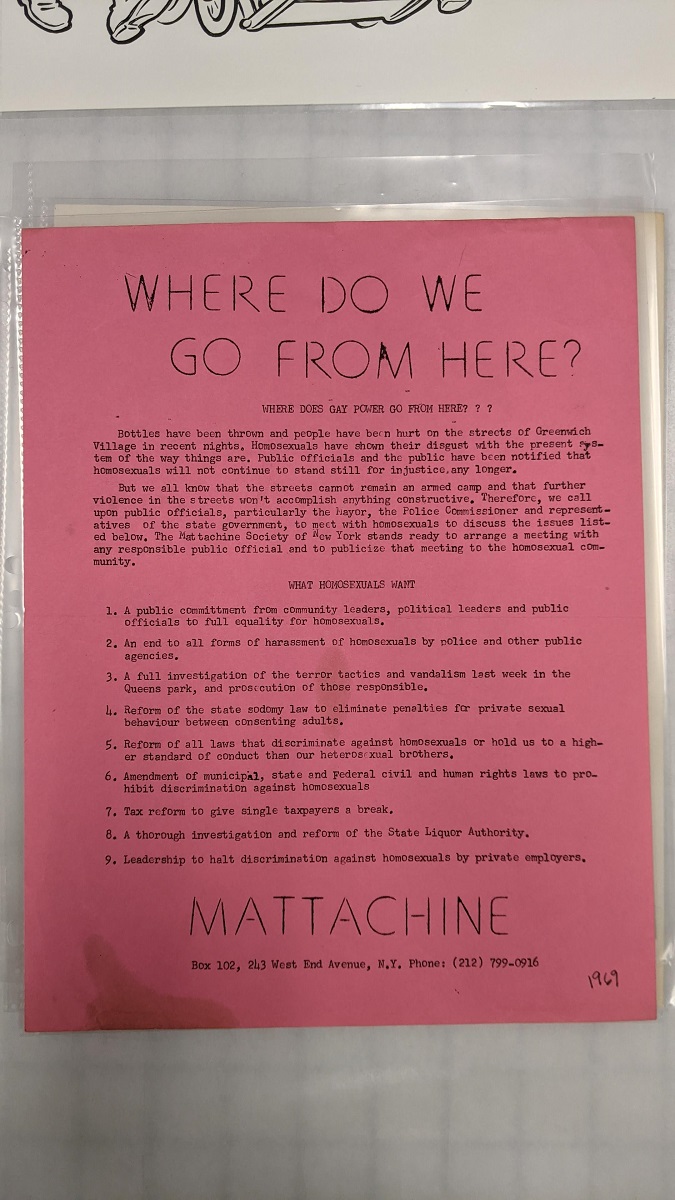

A group of fliers created by the Mattachine Society in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall Uprising, which paints a portrait of the fraught months that followed...

Flier created by the Mattachine Society. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

And a leather Muir cap of the type commonly worn by members of post–World War II biker clubs, which provided freedom and mobility for gay men when persecution and the threat of police raids were ever-present at established gay locales. Its many pins and buttons feature gay biker gang culture of the 1960s and early 1970s.

Leather cap with pins. / Photo courtesy Kristen Gallerneaux

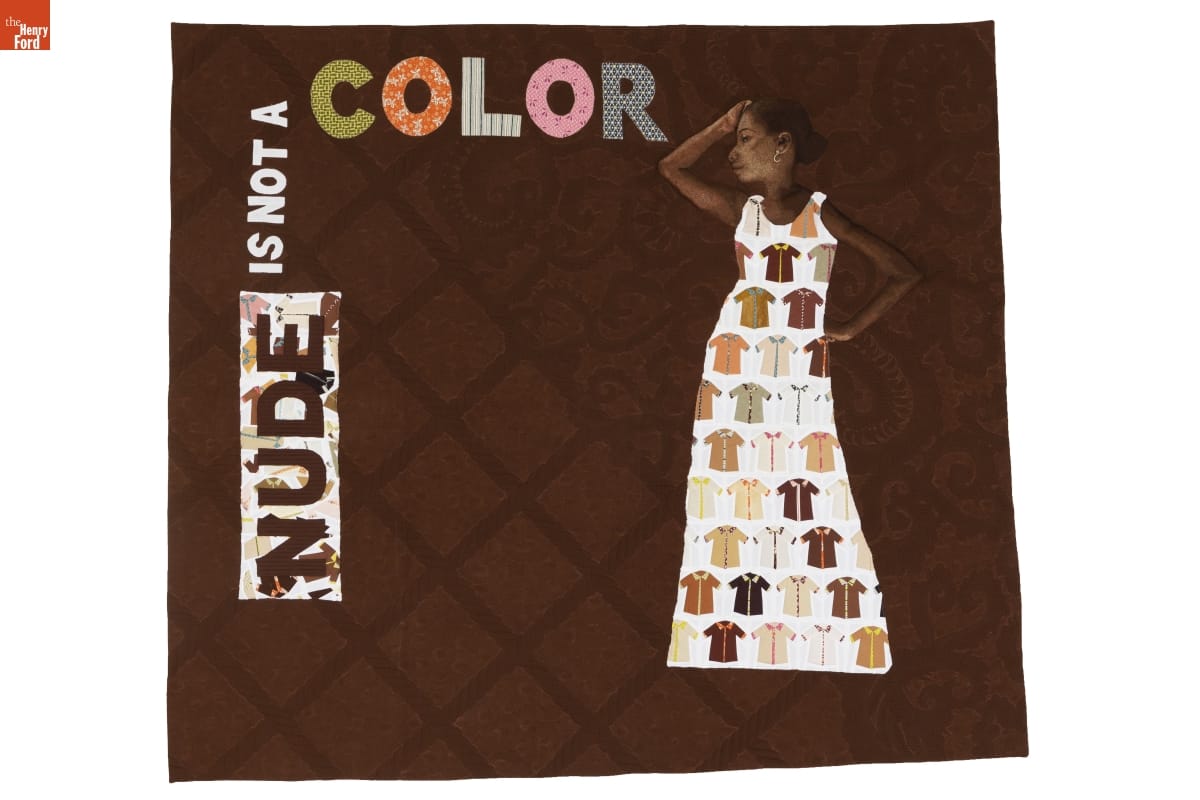

Another acquisition that further diversifies our collection is the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt, recently acquired by Curator of Domestic Life Jeanine Head Miller. This striking quilt was created in 2017 by a worldwide community of women who gathered virtually to take a stand against racial bias.

“Nude is Not a Color” Quilt, Made by Hillary Goodwin, Rachael Door, and Contributors from around the World, 2017. / THF185986

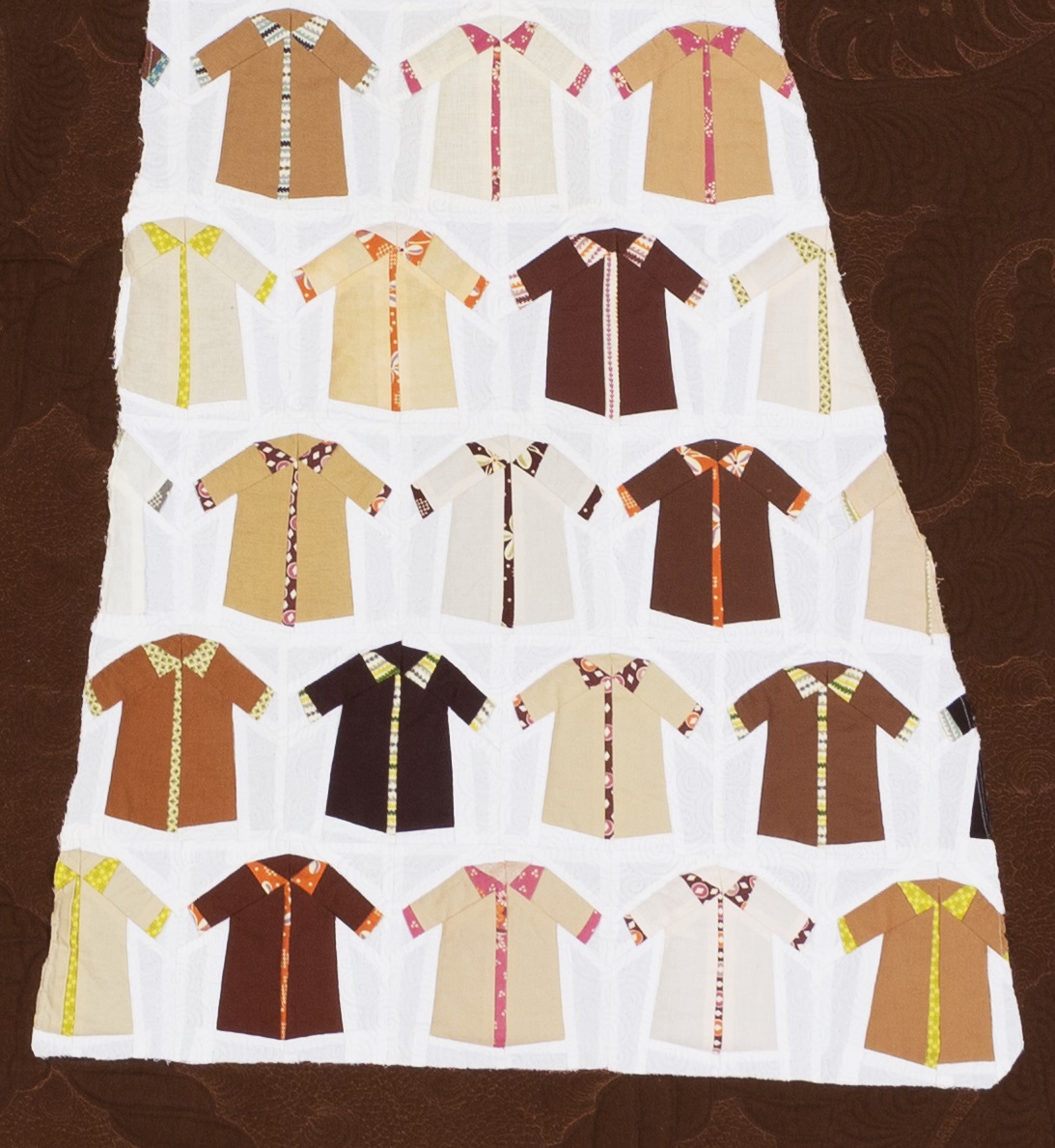

Fashion and cosmetics companies have long used the term “nude” for products made in a pale beige—reflecting lighter skin tones and marginalizing people of color. After one fashion company repeatedly dismissed a customer’s concerns, a community of quilters used their talents and voices to produce a quilt to oppose this racial bias. Through Instagram, quilters were asked to create a shirt block in whatever color fabric they felt best represented their skin tone, or that of their loved ones.

Shirt blocks on the “Nude is Not a Color” quilt. / THF185986, detail

Quilters responded from around the United States and around the world, including Canada, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Spain, the Netherlands, and Australia. These quilt makers made a difference, as via social media the quilt made more people aware of the company’s bias. They in turn lent their voices, demanding change—and the brand eventually altered the name of the garment collection.

Jeanine Head Miller has also expanded our quilt collection with the addition of over 100 crib quilts and doll quilts, carefully gathered by Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy over a period of forty years. These quilts greatly strengthen several categories of our quilt collection, represent a range of quilting traditions, and reflect fabric designs and usage—all while taking up less storage space than full-sized quilts.

A few of the crib quilts acquired from Paul Pilgrim and Gerald Roy. / THF187113, THF187127, THF187075, THF187187, THF187251, THF187197

During 2021, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment Debra Reid has been developing a collection documenting the Civilian Conservation Corps, a New Deal program that employed around three million young men. This year, we acquired the Northlander newsletter (a publication of Fort Brady Civilian Conservation Corps District in Michigan), a sweetheart pillow from a camp working on range land regeneration in Oregon, and a pennant from a camp working in soil conservation in Minnesota’s Superior National Forest.

Recent Civilian Conservation Corps acquisitions. / THF624987, THF188543, THF188542

We also acquired a partial Civilian Conservation Corps table service made by the Crooksville China Company in Ohio. This acquisition is another example of curatorial collaboration, this time between Debra Reid and Curator of Decorative Arts Charles Sable. These pieces, along with the other Civilian Conservation Corps material collected, will help tell less well-documented aspects of the Civilian Conservation Corps story.

Civilian Conservation Corps Dinner Plate, 1933–1942. / THF189100

If you’ve been to Greenfield Village lately, you’ve probably noticed a new addition going in—the reconstructed Vegetable Building from Detroit’s Central Market. While we acquired the building from the City of Detroit in 2003, in 2021, Debra Reid has been working to acquire material to document its life prior to its arrival at The Henry Ford. As part of that work, we recently added photos to our collection that show it in service as a horse stable at Belle Isle, after its relocation there in 1894.

“Seventy Glimpses of Detroit” souvenir book, circa 1900, page 20. While this book has been in our collections for nearly a century, it helps illustrate changes in the Vegetable Building structure over time. / THF139104

Riding Stable at the Eastern End of Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, October 27, 1963. / THF626103

Horse Stable on Belle Isle, Detroit, Michigan, July 27, 1978. / THF626107

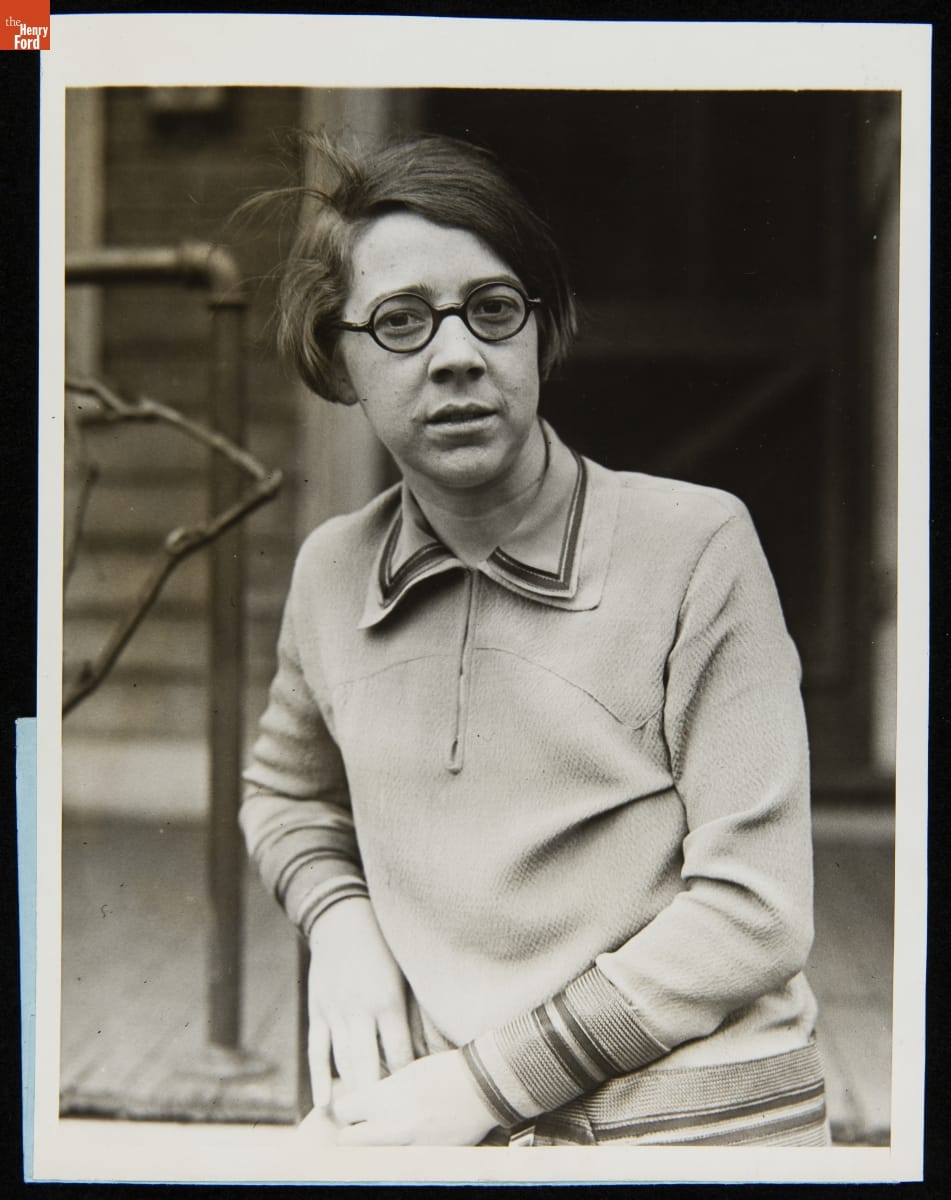

This year, Debra Reid also secured a photo of Dorothy Nickerson, who worked with the Munsell Color Company from 1921 to 1926, and later as a Color Specialist at the United States Department of Agriculture. Research into this new acquisition—besides leading to new ideas for future collecting—brought new attention (and digitization) to a 1990 acquisition: A.H. Munsell’s second edition of A Color Notation.

Dorothy Nickerson of Boston Named United States Department of Agriculture Color Specialist, March 30, 1927. / THF626448

All of this is just a small part of the collecting that happens at The Henry Ford. Whether they expand on stories we already tell, or open the door to new possibilities, acquisitions like these play a major role in the institution’s work. We look forward to seeing what additions to our collection the future might have in store!

Compiled by Curatorial Assistant Rachel Yerke from tweets originally written by Associate Curators, Digital Content, Saige Jedele and Katherine White, and Curators Kristen Gallerneaux, Jeanine Head Miller, and Debra A. Reid for a curator chat on Twitter.

quilts, technology, computers, Herman Miller, posters, women's history, design, toys and games, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid, by Jeanine Head Miller, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Katherine White, by Saige Jedele, by Rachel Yerke, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Touch-Free Mathematica

The Mathematica exhibit in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. / Photo by KMS Photography

When Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation reopened in July 2020 after months of shutdown because of COVID-19 restrictions, museumgoers were excited to be back on the floor. Many of them were super excited to get back to one of their favorite exhibitions, Mathematica—a favorite because it’s so hands-on.

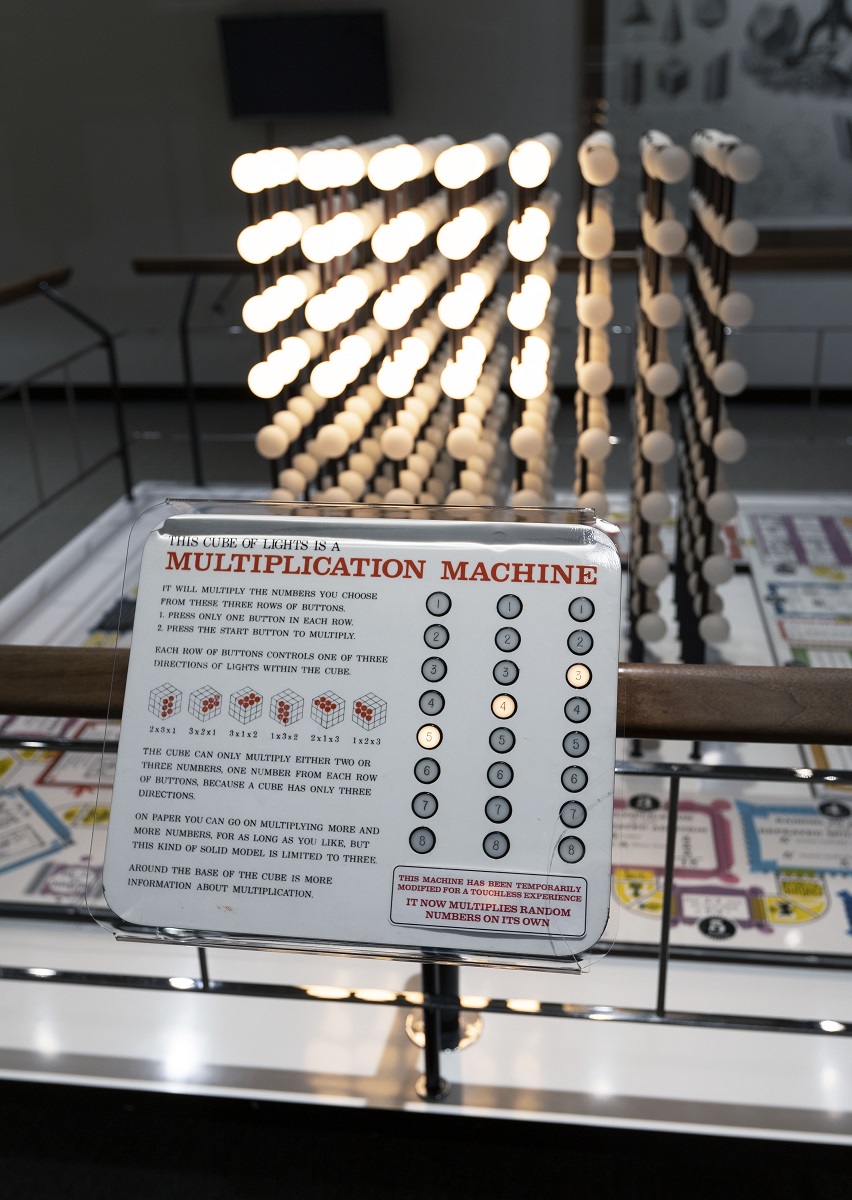

And therein lay the problem, said Jake Hildebrandt, historic operating machinery specialist at The Henry Ford. As COVID-19 spread, the hands-on interactivity of Mathematica caused it to remain closed. Mixing a little bit of ingenuity, technology, and lots of problem-solving skills, Hildebrandt, along with master craftsman Brian McLean, ensured the exhibition could remain interactive yet hands-free and open to the public.

Mathematica’s Moebius Band was modified by staff from The Henry Ford to start via a hand wave. / Photo by Jillian Ferraiuolo

The push-start buttons on the Moebius Band and Celestial Mechanics installations, for example, are now initiated with a wave of the hand—no touch necessary. And the 27-button panel of the Multiplication Machine has been covered with Plexiglas for safety and new software installed so random math problems run on the cube throughout the day for visitor education and enjoyment.

A newly-added note under the Plexiglas installed on the Multiplication Machine in Mathematica reads “This machine has been temporarily modified for a touch-free experience / It now multiplies random numbers on its own.” The styling of the note is intended to match the original design of Charles and Ray Eames. / Photo by Jillian Ferraiuolo

“Projects like these, DIY challenges that have high criteria, limited time and budget, are my favorite kinds of projects,” said Hildebrandt. All the alterations to Mathematica are easily reversible, he added, and when you head to the museum to see them, you’ll notice the respectful attention given to the exhibition’s classic Eames styling.

This post was adapted from an article first published in the January–May 2021 issue of The Henry Ford Magazine.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, The Henry Ford Magazine, making, Henry Ford Museum, healthcare, design, COVID 19 impact, collections care

Introducing the Main Storage Building

Cars are just one type of artifact that have found a good home in our new collections storage facility, the Main Storage Building. / Photo courtesy Cayla Osgood

With more than 26 million artifacts in our collections at The Henry Ford, storing them all can be a challenge—especially the large industrial, agriculture, and transportation objects. That changed a few years ago, when we began working on an exciting and important project for our institution—the creation of our Main Storage Building, or, as we call it, MSB. Our staff answer a few questions about our newest storage building below.

What is MSB?

MSB is a 400,000-square foot building adjacent to Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Ford Motor Company occupies the front half of the building, while The Henry Ford occupies the rear 200,000 square feet of space. Today, 178,000 square feet of the MSB is used exclusively for collections storage. The remaining space in The Henry Ford’s portion of the building is home to shipping and receiving, our photo studio, office space, and institutional non-collections storage.

This 1936 photo of the Ford Engineering Laboratory building gives a sense of its scale. / THF240744

What is the history of the building?

Built in 1923–1924, the Ford Engineering Laboratory housed Ford Motor Company’s tool design, production engineering, and experimental engineering research departments. Henry Ford and Edsel Ford both had offices there and, throughout Henry’s lifetime, the lab was the true heart of Ford. The facility was expanded and remodeled several times over the years but had been vacant for some time before the agreement between Ford Motor Company and The Henry Ford was reached.

You can view hundreds of photographs and other artifacts related to the history of the Ford Engineering Laboratory in our Digital Collections, and you can learn about the design of Henry and Edsel’s offices in the building in this blog post.

Though we only recently acquired the building, this is not the first time our artifacts have been stored at MSB. This 1926 photo shows objects collected for the not-yet-completed Henry Ford Museum being stored in the Ford Engineering Laboratory. / THF124539

How did we acquire our portion of the building?

In 2016, we entered into an agreement with our neighbor, Ford Motor Company, to acquire half of the Ford Engineering Lab building. The contract allows Ford to occupy the front half of the building for office space and their corporate archives, while The Henry Ford occupies the rear 200,000 square feet, now referred to as the Main Storage Building, as full owner of that portion.

The Henry Ford’s collections management staff was very happy to visit MSB on our first day of possession, before any artifacts had been moved in. / Photo courtesy Cayla Osgood

Why did we decide to consolidate our collections storage?

Like many museums, The Henry Ford has faced challenges in storing and caring for our holdings, especially the large industrial, agriculture, and transportation artifacts that make up much of the collections. For decades, we rented offsite warehouse space to house these materials. With them came problems—poor accessibility, overcrowding, landlord and lease challenges, and an inability to invest appropriately in rental property. We have made huge strides in caring for and preserving our collections by moving into MSB, including improved access, easy-to-maintain storage environments, enhanced security, and a reduction of overcrowding in storage areas.

Pallet racking and thoughtfully packed artifacts allow us to fit tens of thousands of objects, both large and small, into MSB, while ensuring both their safety and ease of access. / Photo courtesy Cayla Osgood

How did we consolidate our collections storage?

As you might expect, moving tens of thousands of irreplaceable artifacts, many of them large, heavy, and/or fragile, from offsite storage into a new building was a challenge. Learn more about this long and complex process in this blog post.

How much of THF’s collection is housed in MSB?

The MSB represents more than 70 percent of The Henry Ford’s total collections storage space. The building currently holds over 40,000 artifacts, with more than 10,000 of these digitized and available for browsing in our Digital Collections.

Agricultural implements hang from a wire grid within MSB. / Photo courtesy Cayla Osgood

What types of artifacts are stored in MSB?

Within MSB, you’ll find items from our Michael Graves Collection, Westinghouse Historical Collection, Lillian F. Schwartz & Laurens R. Schwartz Collection, Industrial Designers Society of America Collection, Bruce and Ann Bachmann Glass Collection, Bobby Unser Collection, and American Textile History Museum Collection, to name just a few. The artifacts it holds were created as early as the 16th century and as late as this year, and represent a century of institutional collecting, dating back to Henry Ford’s early collecting a full decade before our official dedication in 1929. You can see some staff-selected highlights from MSB in this expert set.

What types of collections work happen in MSB?

In MSB we had an opportunity to create a new collections operations workroom that acts as a collective workspace for multiple teams, including collections management, registrars, curatorial, and photography. In the workroom, we see collections items both existing and new to the collection. Types of work include cataloging and numbering (for tracking), creating storage mounts and boxes, and staging for research. We also pack artifacts to lend to other institutions.

Our conservation department utilizes two different lab areas to treat all artifacts requiring attention in the MSB—everything from vehicles to glass. Photography of smaller objects happens in the photo studio in MSB or in the workroom, while large object photography happens throughout the building—meaning our photography team is quite adept at working with a variety of space and other constraints. You can read more about some of our large object photography projects in MSB in this blog post.

Large artifacts such as these might be photographed in or near their storage locations in MSB for maximum digitization efficiency. / Photo courtesy Cayla Osgood

Beyond this ongoing work, we are still completing our move into the building—all 40,000+ artifacts are being organized, inventoried, and positioned into their permanent locations throughout MSB.

What enhancements are planned for MSB in the future?

As a significant addition to our campus, many enhancements are planned for MSB to optimize the structure for historic collections. Currently, we are continuing important infrastructural work, like roof maintenance and HVAC upgrades, so our collections have appropriate environmental controls to ensure their physical integrity for many years to come.

Once that is complete, we can turn our attention to maximizing our square footage for both access to the collections and issues of density. Specially designed storage furniture called compact shelving helps alleviate wasted aisle space while keeping objects safe and accessible to curators for research, exhibits, and digital uses. As we unpack, this type of storage furniture will allow us to make the most of the 178,000 square feet we have so that we can continue to collect well into the future.

We are so pleased to have this new space and look forward to sharing much more about the work we’re doing and collections we’re housing in MSB!

collections care, Main Storage Building, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Photographing Artifacts in Our Main Storage Building

While we have a photo studio where we do most of our artifact photography using white backgrounds and strictly controlled lighting, many times we encounter things that are too big for this setting—for example, a car! In those cases, we need to take ourselves and our studio on the move, and our newest collections storage building, the Main Storage Building (MSB), gives us a perfect environment for that. While sometimes space can be an issue (there are only so many places you can store dozens of wagons and plows), we make the most of the room we have and get creative in the meantime.

For example, to photograph “The Busy World” automaton wagon, it first needed to be moved out of a row of wagons and into an open space to give us room to set up our lights and camera.

“The Busy World” automaton wagon in storage in MSB before photography. / Photo courtesy Jillian Ferraiuolo

The completed photograph of the automaton. / THF187282

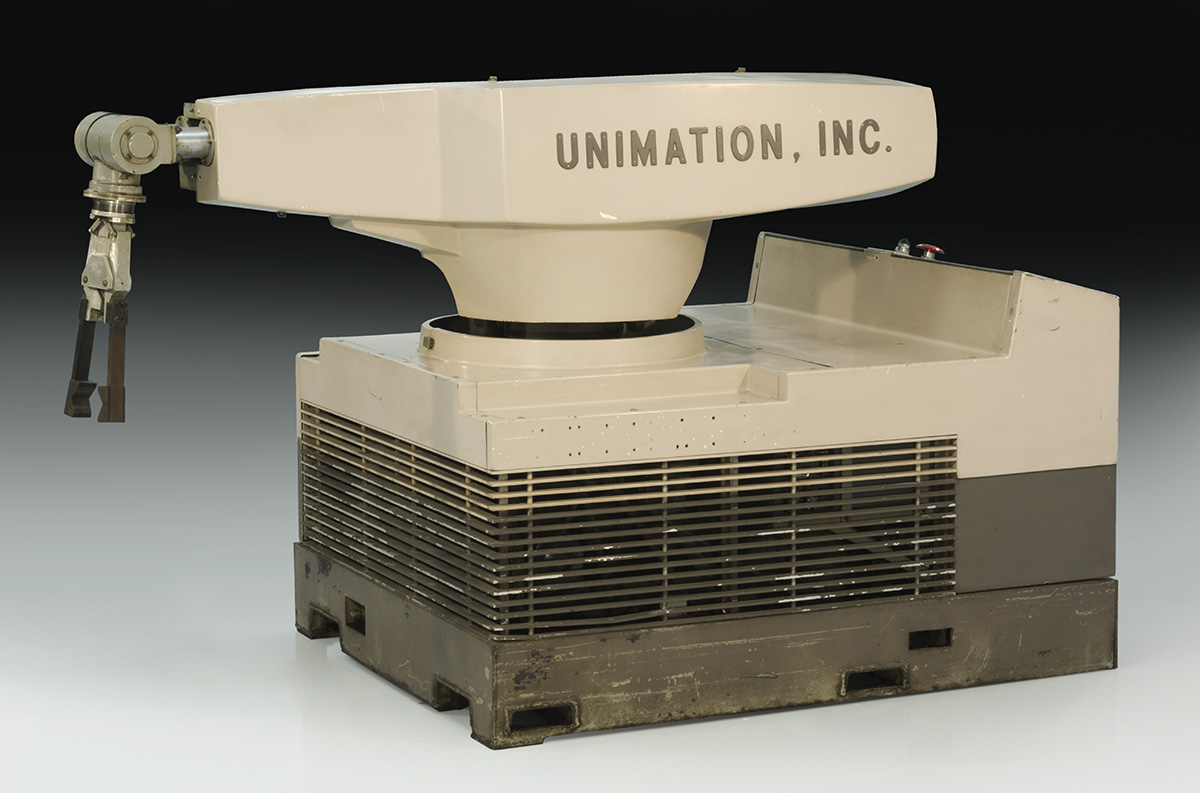

Since the Unimate robot was featured in an episode of The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, we needed to capture new photographs of it for our Digital Collections before the episode aired. While we had a little more room to work when photographing the Unimate (this was before MSB was as full as it is today), we still benefitted from having the ability to set up all around it because it is extremely heavy and cannot be easily moved. We had to use the space around it to access both sides for our standard photography.

Photographing the Unimate. / Photo courtesy Jillian Ferraiuolo

Completed photo of the Unimate robot. / THF172780

It was a similar situation when we photographed the 1977 Ford Mustang II. Though now this area in MSB houses an array of agricultural equipment, such as plows and wagons, in 2018 we were able to use the open area to photograph the Mustang II for the first time so it could be viewed online.

Photographing the Mustang II. / Photo courtesy Jillian Ferraiuolo

Completed photo of the Mustang II. / THF173560

This next example shows a more current look at MSB in 2021. As you might be able to see, there are many more vehicles now occupying the large area where we shot the Unimate and Mustang II. So when we were tasked with the job of photographing a 1925 Yellow Cab, we were unable to circle around it and had to work with our collections management team to move the taxi for us as we documented it.

Photographing the 1925 Yellow Cab taxicab. / Photo courtesy Jillian Ferraiuolo

You can also see that we created our own white background around the cab with tall foamcore boards (a little thing that helps immensely with post-processing in Photoshop). But our “studio” was surrounded by another car to the right and a wagon to the left! All this careful maneuvering and setup was necessary to get the final image.

Final photograph of the 1925 Yellow Cab Taxicab. / THF188014

Looking at the completed image, you probably would never know what it looked like when we were photographing it out on the floor in MSB!

My final example, the Ford COVID-19 mobile testing van, was so tall that it almost reached the ceiling in the tallest room in MSB. Since it’s a full-sized van, it isn’t easy to move—especially inside a building. In case that isn’t enough, its current neighbors in storage happen to be a couple of large fire engines. Regardless, we got creative again and we were able to get photos of the van despite these challenges.

Photographing the Ford COVID-19 mobile testing van. / Photo courtesy Jillian Ferraiuolo

Completed photo of the COVID-19 mobile testing van. / THF188109

Besides being an invaluable space to store an extensive variety of precious artifacts from our collections, MSB also serves as a functional space for us to use as photographers—so we can digitize artifacts even if they’re larger than we can accommodate in our photo studio.

Jillian Ferraiuolo is Digital Imaging Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Main Storage Building, photography, photographs, digitization, collections care, by Jillian Ferraiuolo, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Moving into the Main Storage Building

The Henry Ford has nearly 26 million artifacts in its care—on exhibit in 82 buildings, housed in the Benson Ford Research Center archive, and stored in multiple storage areas. Caring for these collections is an endless task—light levels, temperature and humidity variations, programmatic usage, even the nature of the artifacts themselves (many items in our holdings were never designed to last)—all create difficulties from a preservation standpoint. Even the most apparently durable and indestructible seeming artifacts need to be cared for—whether on exhibit or held in storage.

For many years our greatest storage problems related to off-site storage in buildings that were not intended for museum collections and whose distance from campus made access difficult. This situation changed in 2016 when The Henry Ford entered into an agreement with our neighbor, Ford Motor Company, to acquire half of the Ford Engineering Lab, a 400,000-square foot building immediately adjacent to Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation.

The Henry Ford’s facilities team began a complicated renovation process on the space, newly designated as Main Storage Building (MSB), turning what had been a cubicle warren of offices into a space suitable for storing historic materials. While the process of rehabilitating the building got under way, historical resources staff began determining where to place and how to move a vast range of over 36,000 artifacts—from giant printing presses and steam engines to tiny buttons and toy tea sets.

The first step in the moving process was to identify collections of similar items (for instance, plows) and create an accurate inventory of what was stored offsite. In this early phase of the project, we would gather anything and everything we thought could be part of this grouping, stage it in one area, and check that the accession number (a unique number assigned to every museum artifact that links the object to information and records on the object—essentially, a Social Security number for artifacts) on each item matched the record in our collections management database. When we encountered objects without accession numbers, we considered these “found in collection” items, and assigned them inventory numbers so they could be tracked in the in the future. After all the new records were created and accession numbers verified, we could then track locations using barcodes and scanners.

Implements lined up for inventory. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

Vacuum cleaners ready to be packed. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

Communications and information technology collections gathered for inventory. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

Before packing, we always assess the condition of the artifacts. We look for mold, hazardous materials, or signs of infestation. In most cases, items were vacuumed or dusted before they were packed away, but sometimes they required more attention to mitigate future problems. In these cases, collections were either isolated or cleaned by conservation staff in one of two labs that were set up in the new building before being moved to their final location within MSB.

The conservation team (pre-pandemic) cleans oversized artifacts in our new lab to prepare them for storage in MSB. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

When packing up the collection, we packed similar items together using archival-quality materials. The move team developed a packing system that could be applied to nearly all of our artifacts. This standardization helped us create more space-saving density in the new building, and helped us to move faster, as we didn’t need to reinvent the wheel every time we encountered a new type of artifact.

Our packing systems were designed to handle both movement and storage, and included these tools and tactics:

- Pallet box containers are stackable gray containers that can be filled with small collections, often housed in custom-built boxes that we created.

- Flat pallets are used for heavy objects secured to pallets with plastic banding. Sometimes we attach plywood to the top of the pallets to create a flat surface.

- Flat pallets with sleeves are used for lightweight objects secured to pallets with Velcro or ties. The pallet is wrapped in a pallet sleeve for additional protection.

- Crates. While we don’t build crates in our department, we do repurpose them for use with heavy, difficult, or fragile artifacts.

- Soft-packing is wrapping artifacts entirely in soft foam or blankets.

- No packing at all is sometimes warranted. Not everything can be packed with packing materials, so such items are carefully strapped onto or into a truck.

Packed collections ready to move, including flat pallets, custom boxes, and pallet boxes. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

Our original moving schedule was spread over 24 months—but then came the COVID-19 pandemic. To meet the changing needs and budget of the institution, we streamlined our operations and adapted our process to accommodate additional staff and contractors to move as quickly as possible while maintaining our standard of collections care and keeping staff safe and healthy. Twenty-four months became nine months—nine months in which we processed, packed, and moved over 17,000 artifacts to complete the move out of offsite storage.

While collections operations staff handled the majority of the objects, we relied on help from three types of contractors: professional car movers, rigging experts, and professional art handlers.

Using professional car movers allowed us to move more than one vehicle at a time, which greatly increased our speed.

The Warrior is loaded into a semitruck (pre-pandemic). / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

The rigging experts had bigger forklifts, trucks of all sizes, and cranes for moving our largest objects.

A steam traction engine is lifted onto custom-built dollies to roll out of the offsite warehouse. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

Finally, professional art handlers were called on to handle and move furniture from our collection, and to offer extra hands to pack and move glass, ceramics, and communications collections located in the warehouse.

Furniture collections stored in MSB. / Photo by Kathleen Ochmanski

We also mobilized our fellow staff members to accelerate the move. Registrars worked at the warehouse each week for six months, helping us complete the inventory phase of the move and soft-packing what they could along the way. Team members from the conservation department worked on artifacts as they arrived at MSB and also ventured to offsite storage during the final three months of packing to help clean the artifacts before they were packed. Also, we can’t thank our shipping and receiving staff enough for helping offload our non-standard objects. We could have never accomplished our nine-month goal without all of these dedicated staff!

On Tuesday, March 16, 2021, the final artifact made its way from the warehouse to MSB. The core team and all who collaborated were there to witness the 606 Horse Shoe Lounge sign loaded onto our truck for the final journey. The sign belonged to the “oldest and last” remaining nightclub from Detroit’s legendary Paradise Valley neighborhood. This last artifact represents the end of an era for Detroit—and for The Henry Ford’s offsite collections warehouses.

Team photograph with the last artifact to leave the warehouse. / Photo by Rudy Ruzicska

MSB is now home to more than 40,000 artifacts previously located in offsite and onsite storage areas, as well as recent new accessions. Centralizing our collections in MSB is an important step in helping us advance collections care through increased access and improved environments. Most importantly, MSB has allowed us to consolidate a large portion of our collections and our collections work into one building, a first for The Henry Ford. While these items are now successfully located in our new building, we continue to work to make MSB truly shine.

Our move from offsite storage has come to an end, and as we continue to unpack, rearrange, and further consolidate our stored collections (there are 14 storage areas onsite…) we are looking forward to sharing more of what MSB has to offer!

Cayla Osgood and Kathleen Ochmanski are Assistant Collection Managers at The Henry Ford.

Main Storage Building, COVID 19 impact, conservation, collections care, by Kathleen Ochmanski, by Cayla Osgood, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Collecting Today for Tomorrow: Contemporary Collecting, COVID-19, and Ford Motor Company

When you think of museums—particularly history museums—it seems to make sense that they are inevitably all about the past. From an artifact collecting standpoint, there is an element of truth to this—most anything a museum can collect already exists and is already sliding into the past. But, putting aside ideas about the swift passage of time, it is important to understand that many museums—including The Henry Ford—do engage in what is known as “contemporary collecting.”

Contemporary collecting seeks to document history as it is happening, and relates to significant current events, trends, or cultural moments. When this collecting is done in the heat of the moment, especially when the conditions being documented are ever-changing or incredibly brief, it is known as “rapid response” collecting. Rapid response collecting relies on a well-tuned sense of what events will have greater historical significance—even after they are over—and requires a particularly proactive approach to gathering information and objects.

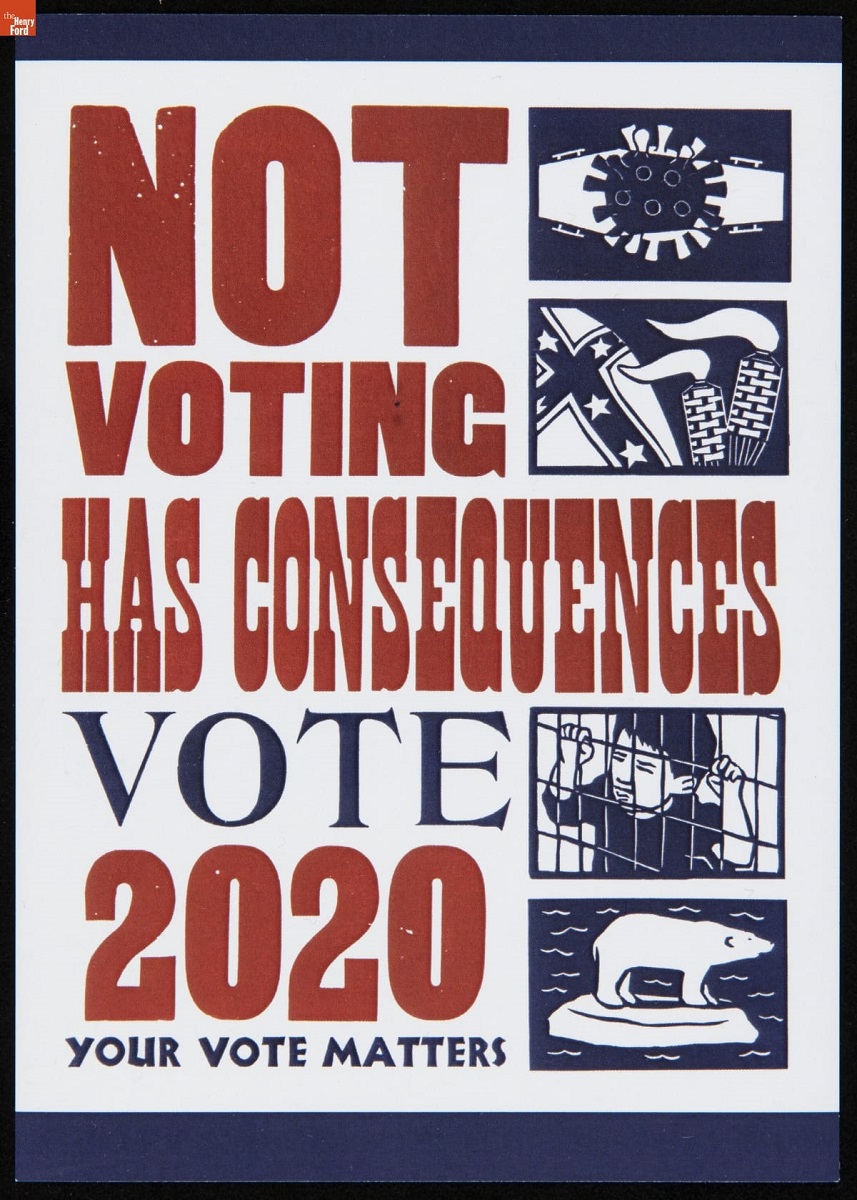

One example of contemporary collecting occurs every four years, when The Henry Ford collects material related to the presidential election cycle. This postcard, created by Sea Dog Press, is from our 2020 collecting initiative. More examples from that initiative can be found here. / THF622210

In early 2020, the world was overtaken by the COVID-19 virus. It soon became clear—as industries ground to a halt, scores of workers were sent home, and international travel all but ceased—that the pandemic would become a major moment in history. Upon this realization, the curatorial staff of The Henry Ford went to work, developing a rapid response plan to document the still-unfolding pandemic. When developing this plan, the curatorial staff was keen to ensure that these collecting efforts not only captured a vivid perspective on the pandemic but also built upon the uniqueness of our collections. They determined to focus on three broad themes: innovation on a nationally significant level, grassroots resourcefulness on the part of individuals, and ingenuity demonstrated by businesses and entrepreneurs. Within each of these categories, curators identified topics that had already begun to emerge, and noted potential objects or types of objects that could be acquired.

With the plan complete, it was presented to The Henry Ford’s Collections Committee—the chartered committee responsible for reviewing and approving all proposed additions to the collections of The Henry Ford. The majority of the committee’s business consists of taking a final vote as to whether or not an item should be accessioned—the term for officially adding an item to the collection. However, some acquisitions are discussed with the group before curators begin making final preparations to acquire them; this gives the committee an opportunity to weigh in on proposed acquisitions that may be more complex, or that would require a greater outlay of the institution’s time or resources. The committee also approves all collecting initiatives, as they typically involve special effort, or result in a larger number of acquisitions; having the committee’s endorsement ensures that the collecting can be adventurous and creative but within clear parameters. Once approved by the committee, the COVID-19 Collecting Initiative was put into place, and curators began gathering information and materials.

Our COVID-19 collecting initiative included outreach to people with items of interest, such as Brighid "Birdie" Pulskamp, a Diné craftswoman who created a beaded facemask featuring a traditional Navajo wedding basket design, as well as fabric masks that she sent to the Navajo Nation to help combat the spread of the virus on reservations. / THF186023, THF186021

While many acquisitions for the collection are actively sought out by our staff, others end up finding us. On September 9, 2020, Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson returned to Collections Committee with word that Ford Motor Company—with whom we have a long and fruitful relationship, particularly in regard to collecting—had reached out to him regarding a prototype COVID-19 testing van that they had developed. Ford Motor Company’s COVID-19 response—particularly their shift from manufacturing automobiles to producing equipment and supplies to aid in the fight against COVID-19—had already been a point of interest on our radar, and had been specifically identified in the collecting initiative.

After hearing the details of the acquisition, the Collections Committee gave Matt a “consensus to proceed” with the acquisition. Consensuses to proceed are given after an initial discussion of a potential acquisition, but before said acquisition is presented for final accessioning; they allow curators to proceed with making any necessary arrangements—like shipping—without overcommitting the institution, should the circumstances of an acquisition change.

Ford Transit Van, Modified for Use as a COVID-19 Mobile Testing Facility, 2020. / THF188109

In working with Ford Motor Company to arrange the donation of the COVID-19 testing van, Matt had the opportunity to discuss other COVID-19–related material that Ford had produced. Of particular interest were the ventilators produced at Ford’s Rawsonville plant. Ford indicated that they would be willing to offer us not one but three of those ventilators: a standard one, one signed by the Rawsonville workers, and one signed by President Donald Trump during his visit to the plant. Would The Henry Ford be interested in all three?

pNeuton Model A-E Pneumatic Ventilators produced by Ford Motor Company, 2020. / THF185924, THF185919, THF186031

In considering objects, The Henry Ford also considers the stories they represent, and these three ventilators were no different. While one alone would have served to document Ford’s manufacturing response, collecting all three would allow us to tell a more multi-layered story. The blank ventilator is just like all the others that rolled off Ford’s assembly line; the one signed by the Rawsonville employees documents and celebrates the people who made Ford’s manufacturing feat possible; and the one bearing President Trump’s signature captures his historic visit to the plant. While we are always cautious of over-duplication in our collection, in this instance, while the objects themselves were similar, the elements of the story were distinct, and all were important to document via our collection.

In addition to the COVID testing van and ventilators, Ford Motor Company also offered numerous pieces of PPE (personal protective equipment) they had prototyped or produced: ventilator connectors, masks, face shields, a gown, and a door pull. Matt accepted all of these items and began preparing them for presentation to Collections Committee, crafting a justification for their addition for the collection and writing a brief summary of their historical significance. On November 11, 2020, the Collections Committee gave their final seal of approval, voting to approve the addition of the van, ventilators, and assorted PPE to The Henry Ford’s collection. With that, the process of rapid collecting—at least in the case of the Ford COVID-19 response acquisitions—had come full circle.

As it turned out, though, just as the pandemic continued on, so too did our collecting opportunities. Ford Motor Company reached out again in the new year with more PPE—this time, though, created for a very unique event: the 2021 inauguration of President Joseph Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris in Washington, D.C. Ford had produced 15,000 single-use masks—in two designs, printed by Hatteras, Inc., in Plymouth, Michigan—to provide to those attending the ceremony. Matt Anderson gratefully accepted the 10 masks Ford offered us, noting their significance, as their production not only furthered Ford’s efforts to combat the spread of the virus, but also demonstrated Ford’s commitment to, in the words of the company’s president and CEO, Jim Farley, “a tradition so fundamental to our democracy.” Just like the testing van and other COVID-19 materials donated by Ford, these masks were presented to the Collections Committee for final approval, which was readily granted, and they became an official part of the collections of The Henry Ford.

This face mask, produced for the 2021 inauguration, represents a unique overlap of two contemporary collecting initiatives undertaken by The Henry Ford: documenting the 2020–2021 presidential election cycle and documenting the COVID-19 pandemic. / THF186524

Thanks to the quick thinking and eager work of the curatorial department and the efficient processes of the Collections Committee, The Henry Ford was able to start documenting the COVID-19 pandemic as it was happening, and—with the help of a well-established relationship with Ford Motor Company—quickly tick an important item (and then some) off our collecting wish list. The thoughtful work of our staff and the relationships they build with outside organizations prove time and again to be key elements of building our collections, whether that be through collecting the past or the present.

Rachel Yerke is Curatorial Assistant at The Henry Ford.

Washington DC, 21st century, 2020s, presidents, philanthropy, Michigan, manufacturing, healthcare, Ford Motor Company, COVID 19 impact, cars, by Rachel Yerke, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Two Makers from Greenfield Village’s Liberty Craftworks Community

In Greenfield Village’s Liberty Craftworks district, skilled artisans practice authentic period crafts and trades with techniques that are, in some cases, centuries old. Here, we ask two of our talented Liberty Craftworks staff, both of whom have worked at The Henry Ford for more than a decade, why they like to make things with their hands.

Joshua Wojick: Crafts and Trades Program Manager, The Henry Ford

Mediums: Glassblowing, Mixed-Media Sculpture

Years at The Henry Ford: 16

A student at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit in the 1990s, Joshua was interested in industrial design, thinking about going into the automotive industry. Then he decided to take a glassblowing class. “I was hooked instantly,” he said. “It spawned my love of craft, of materiality and the honesty of material, of making.”

He changed majors and has never looked back.

Photo courtesy of Joshua Wojick.

At The Henry Ford, he appreciates the boutique expression of production afforded by the Liberty Craftworks community. “It’s a tough world getting into strict production craftmaking. It takes specific focus to make the same things over and over again. When you get to see it in a smaller setting—where artists are working, controlling, understanding the material moment by moment—it draws you in. That is what’s unique to The Henry Ford.”

He is also grateful for the guests he can interact with in Greenfield Village during daily demonstrations. “I have always looked at this interaction as the driving force of the Craftworks community. As artists, we have the opportunity to meet unique people and hear their life journeys, which can help you think differently throughout the day.”

Photo courtesy of Joshua Wojick.

Joshua never stops making things, creating award-winning art inside as well as outside of The Henry Ford. See more of his work at joshuawojick.com.

Melinda Mercer: Pottery Shop Lead, The Henry Ford

Mediums: Wood-Fired Porcelain, Salt-Glazed Stoneware, Patchwork Quilting

art, making, Greenfield Village, by Jennifer LaForce, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Years at The Henry Ford: 17

Melinda has loved pottery for decades, first enthralled by its artistry as she watched her high school art teacher throw clay on his potter’s wheel and next while earning her fine arts degree. Then, as an intern at The Henry Ford a few years later, she had the privilege of tutelage under Bryan VanBenschoten, a lead potter in the Pottery Shop for nearly 40 years.

Photo courtesy of Melinda Mercer.

One of her favorite things in the world is wood-firing in the shop’s wood kiln. She calls it a labor of love, a rewarding team effort that the potters do only once or twice a year. “It takes us months to prepare,” she said. “And once we start putting wood in the kiln, we have to stay with the kiln for 30 hours, loading more wood every couple minutes. There’s no electricity, no technology. Just us, the wood, and the fire.”

Melinda loves the individuality the wood-firing process affords her. “We really get to stretch artistically,” she said. More importantly, she can share the experience with guests at The Henry Ford. “The wood-firing is a magical event—when visitors see the flames shooting from the top of the kiln, their reactions are quite remarkable.”

Continue Reading

Classical Details: A Close Look at the Noah Webster Home

The Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village. / THF1882

The Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village was originally designed and built in New Haven, Connecticut, over the course of 1822 and 1823. The home, designed by David Hoadley, is built in the Classical Revival style, popular in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

The house is loaded with wonderful classical details, some of which include carved Ionic capitals topping solid chestnut fluted columns on the front portico (very appropriate, as they represent wisdom in the Greek order), fluted pilasters (rectangular columns) with side lights and a fan light (window) over the front door, and interesting wooden mutules (large decorative wooden blocks with holes evenly drilled over the surface) lining the underside of the cornice or the soffit. Mutules are elements found on ancient Greek and Roman temples and were originally decorative elements found on rafter ends. The cornice surrounds the pediment (the triangular portion) on the front of the house and runs under the eaves or soffit all around the perimeter.

The front portico of the Noah Webster Home features fluted columns with carved Ionic capitals. The soffit of the roof includes dentil details (more below) and a very fine bead trim at the lower edge. The doorway’s fluted pilasters carry through the column elements with the same carved Ionic capitals. The front door with its fan light is a reproduction based on original examples found in the New Haven region, and the door hardware is also a reproduction of a fine imported English lock set. The porch, steps, and column plinths, along with the front foundation blocks, are all brownstone. / Photo by Jim Johnson

The above shots show details of the mutules on Webster Home. These architectural ornaments were inspired by details found on ancient Greek and Roman temples, and were often seen as ornamentation for rafter ends that would extend under the eave. The details within the mutules were completed in sets of six and could also include “drops” and additional elements that would connect at a right angle to the frieze below the eave cornice. Our examples use a round drilled pattern in sets of six. / Photos by Jim Johnson

All the windows have decorative lintels (horizontal supports at the top), which are further decorated with rows of small blocks known as dentils, because they indeed look like rows of teeth. So, our Webster Home has lintels with dentils. The cornice of the front portico (a roof supported by columns) also features a larger set of dentils, and a very delicate bead molding on the edge of the cornice.

The photos above show details of the decorative window lentils, ornamented with dentils, small wooden blocks that resemble rows of teeth. / Photos by Jim Johnson

Another interesting note about the front façade of the building has to do with the center second-floor window over the portico. Originally, there was not a real window in that opening—it was a dummy window originally included to balance the fenestration (design of the window and door openings) on the façade of the house. All the original site photos show that window with a closed set of blinds (note that shutters are solid covers, whereas blinds have louvers). In recent years, I have worked with our carpentry staff to permanently close the blinds of the “new” window added to the house by Edward Cutler in 1936 in order to return the front of the house to its original appearance.

There was never an actual window in the second-floor center opening. The closed blinds create the illusion of a window that balances the front façade with equal openings top and bottom. / Photo by Jim Johnson

All of these above-mentioned decorative elements continue into the rear of the house, including a very charming small back porch that features transom windows over both back doors and fluted columns with carved Ionic capitals. Also at the rear is the third-floor attic that features a pair of quarter-moon windows, a style immortalized in the house from The Amityville Horror. (This is not lost on an entire generation of our movie-going guests, so we light those windows red for Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village.)

Quarter moon windows on the rear elevation provide light for the attic stairway. The decorative mutule elements can clearly be seen on the soffit of the entire cornice, including the later brick addition. / Photo by Jim Johnson

I should note that due to significant changes to the rear of the house in the nineteenth century, and its reconstruction into a hillside in Greenfield Village, many alterations were made. But, in doing so, the original architectural features were carried forward with excellent craftsmanship and design.

These images show the architectural details of the rear portico. Because of significant changes to the rear of the house in the 1860s, and its reconstruction into a hillside in Greenfield Village, modifications were made to the backside. None the less, original architectural elements were carried through with very high levels of craftsmanship and design. / Photos by Jim Johnson

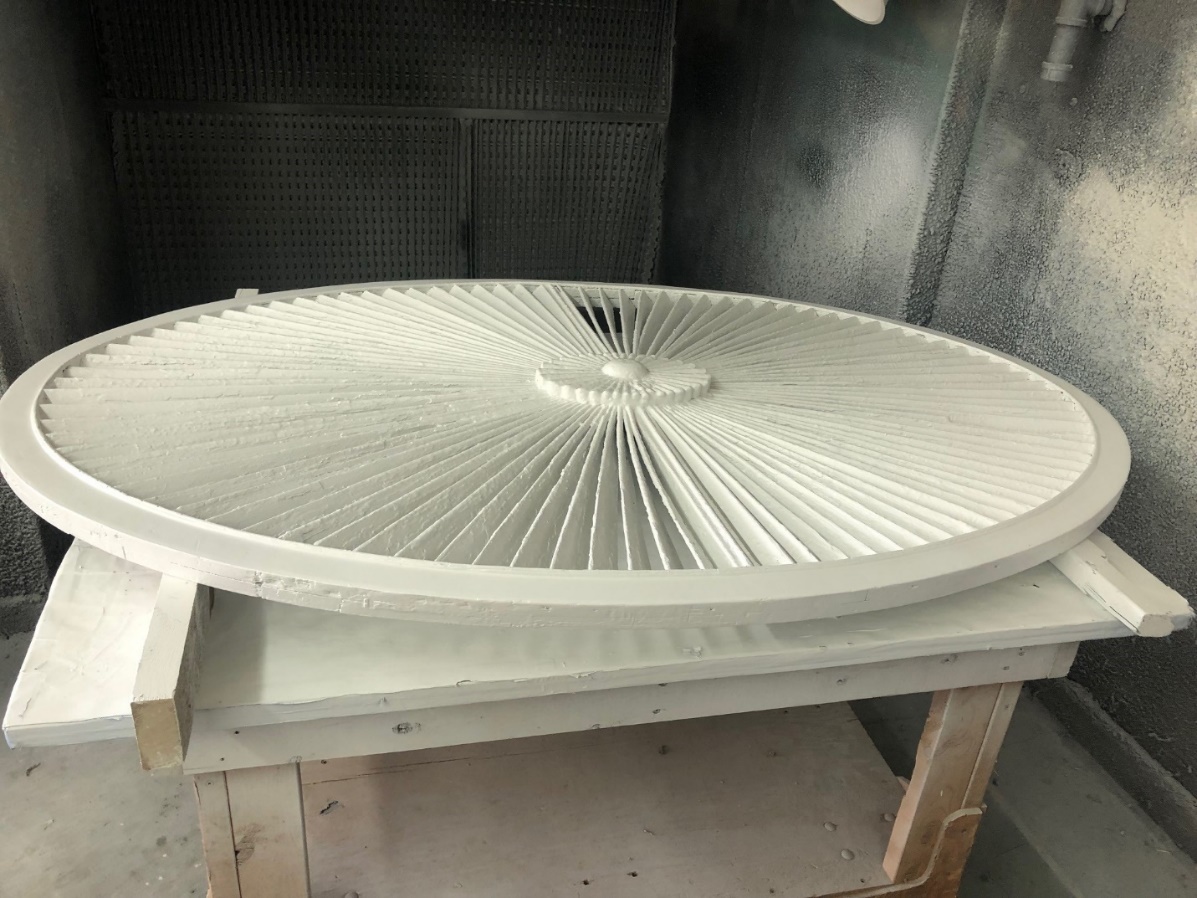

If all these beautiful details were not enough, front and center in the triangular pediment on the front elevation, acting as a focal point, is a louvered ellipse (oval), which was undoubtedly handmade by a master craftsman (anonymous to us today) in New Haven in 1822. It consists of thin pieces of wood that create a louvered fan radiating from a carved central floret design, all set in a wooden oval frame, or ellipse. Though wonderfully decorative, it also served a function, allowing air and some light into the attic space. In letters sent by Rebecca Webster to Noah Webster while he was away on a long overseas research trip in the 1820s, Rebecca mentions laying out pippins (apples) in the attic.

Early-twentieth-century photographs of the house on its original site in New Haven clearly show the Victorian/Italianate additions that were added to the exterior of the house in 1868 by the Trowbridge family. The Trowbridge family is connected to Mary Southgate, the Websters’ granddaughter, who was raised in the house and married Henry Trowbridge in 1838. They did not take possession of the house until 1849, when it was deeded to them by the Webster estate.

Mary died in 1860 and Henry remarried, thus ending the direct Webster association with the house. Henry took on the renovations of the house with his second wife to make the house more fashionable, both inside and out. In doing so, most of the original Federal-style architectural elements were removed, primarily inside, and were replaced with heavy dark walnut woodwork, doors, and a carved staircase. The interior updates also included marble fireplace surrounds and plaster medallions in all the main room ceilings.

The exterior alterations and additions take the form of one- and two-story bay windows and a large brick addition to the rear of the house. A new Italianate-style dark walnut front door and surround was also installed. Surprisingly, many of the early-nineteenth-century architectural decorative elements were included within the Victorian/Italianate additions, likely to create continuity. This can be seen in the early-twentieth-century photographs that show that mutules have been added to the soffits of all of the 1860s bay windows and the brick addition. At some point, likely in the early twentieth century, all the windows were replaced with large one-over-one pane sashes.

This image, taken March 31, 1934, as part of the Historic American Building Survey, shows the Webster Home on its original site at the corner of Temple and Grove Streets in New Haven, Connecticut. It clearly shows the late 1860s Italianate additions in the form of second-floor bay windows, an Italianate-style front door and surround, and updated one-over-one pane windows. The house was in use as a dormitory by Yale University at the time this photograph was taken. / THF236363

A view of the rear of the house in New Haven, circa 1936, showing the original configuration on level ground. The square Italianate addition and second story bay window were added in 1868. / THF236377

In 1936, Yale University decided to sell the Noah Webster Home to a demolition company for salvage, to make way for new construction. Edward Cutler recalled that the one thing Yale was interested in was the ellipse—for the art school, due to its extraordinary design and craftsmanship. Luckily, Henry Ford’s representatives were able to purchase the house from the demolition company before many of the decorative elements had been stripped off.

Since 1936, the front pediment of the Webster Home has undergone many repairs, siding replacement, and painting. It faces almost full west and takes a beating from the elements. Yet not until now has the ellipse been removed and examined more closely.

Recently, our carpentry team carefully removed the ellipse and took it back to their shop to undergo some repair work. The decision was made to not replace any of its elements, but rather to stabilize the original louvers and do some reinforcements to the center floret element. Further work was done to ensure that no water can get in or around any part of the ellipse. New siding was custom milled for the pediment, including areas where it joins the ellipse, and the molding that surrounds it was restored. Several coats of new paint will further protect this amazing and beautiful survivor.

These images show the 199-year-old decorative ellipse from the front pediment of the Noah Webster Home. It underwent conservation efforts and received several coats of new paint in preparation for its return to its rightful location. / Photos by Jim Johnson

The three images above show the original ellipse being reinstalled in the pediment. / Photos by Jim Johnson

The renovation of the façade of the Noah Webster Home is now complete as the ellipse has returned to its place of honor, ready to withstand the elements for another 200 years. Kudos to the talented carpentry and painting staff of The Henry Ford!

The completed renovation of the façade of the Noah Webster Home. / Photo by Jim Johnson

So, the next time you walk by the Noah Webster Home in Greenfield Village, slow down a bit and linger to allow time to take in the all the details that were intended to be seen—when the speed of life moved at a very different pace, two centuries ago.

Jim Johnson is Director of Greenfield Village & Curator of Historic Structures and Landscapes at The Henry Ford.

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, collections care, by Jim Johnson, Noah Webster Home, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village

“Donation - Crash Test Dog” isn’t the type of subject line you typically see on an email. Yet just after Thanksgiving in 2019, that’s exactly what landed in the Benson Ford Research Center’s email queue. Sleepypod, makers of safety-conscious pet carriers and other related pet products, wanted to know if The Henry Ford would be interested in the donation of MAX2, one of the early crash test dogs they had designed to simulate a live pet in a series of crash tests used to demonstrate the increased safety of Sleepypod pet carriers. For the curator’s consideration, Sleepypod provided photos of MAX2, as well as a brief history of how and why he was developed.

Sleepypod “MAX 2” Crash-Test Dog, 2012 / THF185385

The offer went off to Curator of Transportation Matt Anderson. Intrigued, Matt wanted to follow up on a few questions with the folks at Sleepypod. Of first concern: would Sleepypod be able to hold on to MAX2 until the new year? With just over a month left in 2019, there would be very little time to get MAX2 on site, develop a comprehensive write-up, present it to The Henry Ford’s Collections Committee for approval, and get a deed of gift sent off to—and returned by—Sleepypod. Thankfully, Sleepypod was happy to hold onto MAX2 for us.

Matt was also interested in knowing if the donation would include one of Sleepypod’s pet carriers, and if there was any associated press or marketing material they would be willing to include. Collecting these additional items would help us tell a more complete story about the company and their innovation. Sleepypod responded that not only would they be happy to offer MAX2 with a carrier and marketing material, they would also be interested in donating CLEO 1.0, their first crash test cat. Matt eagerly accepted their offer.

Sleepypod “CLEO” Crash-Test Cat, 2015 / THF185386

In January 2020, MAX2 and CLEO made it to their new home at The Henry Ford, by way of arrival at our relatively new Main Storage Building (MSB). In previous years, objects would arrive at the curatorial offices in the Benson Ford Research Center, where they would be deposited in a small holding room until formally approved and accessioned; they would then be taken elsewhere for storage. MSB, however, is equipped with two rooms dedicated to new acquisitions—one where objects can be examined by our conservation staff to make sure they do not pose a risk to other objects (via issues like insect infestations), and another where “clean” objects can be stored on compacting shelving until they are accessioned and assigned a permanent location, typically within the same building. Utilizing MSB in this way not only helps us keep better track of pending acquisitions, but also saves time and effort on behalf of our Collections Management team, as they have less distance to move objects after they have been accessioned.

Matt began prepping MAX2, CLEO, the carrier, and associated material for presentation to Collections Committee, the group responsible for approving all additions to the collections of The Henry Ford. In order to make his case for adding these crash pets to the collection—after all, “adorableness” is in the eye of the beholder, and not an adequate justification for acquisition—Matt pulled together information on Sleepypod’s history, the development of MAX2 and CLEO, and the historical significance of a pet carrier designed with safety in a moving car in mind (an advancement that shows the next evolution of transportation safety, now that human lives have benefited from crash test technology). All of this was distilled into a short write-up, intended to give the committee a broad overview of the potential acquisition and the rationale behind suggesting it.

Sleepypod Pet Carrier, 2019 / THF185389

Collections Committee—likely won over by a combination of Matt’s thorough and engaging write-up, and the surprise guest appearance of MAX2 and CLEO as meeting attendees—approved adding MAX2, CLEO, the Sleepypod carrier, and the associated marketing material to the collection. The group of items was assigned an accession number—2020.31, denoting that it was the 31st accession group brought into the collection in 2020—and the registrars assigned each of the 3D objects a number within that group: 2020.31.1 for the Sleepypod pet carrier, 2020.31.2 for MAX2, and 2020.31.3 for CLEO. The photography studio photographed MAX2, CLEO, and the carrier, so that the objects would be ready to go up on our Digital Collections page, which provides photos and information for over 100,000 items (and growing) in The Henry Ford’s collection.

After the Collections Committee meeting, there was one final step to officially transfer ownership of MAX2 and CLEO to The Henry Ford: completion of deed of gift paperwork. Generated by the Registrar office for all donations that become part of the collection, the deed of gift serves as a legal document that formally transfers ownership of an object to The Henry Ford. It also provides an opportunity for donors to indicate how they would like to be credited if the object is ever exhibited, published, or otherwise presented to the public. Once this paperwork is completed by a donor and returned to The Henry Ford, the acquisition process comes to an end.

CLEO relaxing, waiting to be moved to her new home by her new owners / Photo courtesy Sophia Kloc

Although MAX2 and CLEO are certainly unique objects, the process by which they came to be part of The Henry Ford’s collection is the same one that every object must take. Although some acquisition offers (like the Sleepypod donation) result in a quick turnaround, others require more thought and research; while the process itself remains the same, the timeline is unique from object to object.

Without the wide variety of offers that The Henry Ford receives, our collection would not be what it is today. Sometimes the most interesting items we acquire are ones we would not have thought to look for, had someone not sought us out with an opportunity. Although we cannot accept everything—over 90 years of collecting means that many things are already represented in the collection, and other items just may not be a good fit for one reason or another—we always take the time to review the offers we are sent, never knowing when the next exciting acquisition may appear.

If you, too, are interested in providing an addition to the collections of The Henry Ford, information on how to start the process can be found here.

Rachel Yerke is Curatorial Assistant at The Henry Ford.

collections care, philanthropy, cars, by Rachel Yerke, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford