Posts Tagged #behind the scenes @ the henry ford

Until We Meet Again

First of the 2020 crop of Firestone Farm Merino lambs: twins born April 11. A ram and ewe are showing a few of the prized wrinkles.

As I begin my second full year as director of Greenfield Village, I was truly looking forward to welcoming everyone back for our 91st season and sharing the exciting things happening in the village. Instead, as we all face a new reality and a new normal, I would like to share how, even as we have paused so much of our own day-to-day routines, work continues in Greenfield Village.

As we entered the second week of March, signs of spring were everywhere, and the anticipation, along with the preparations for the annual opening of Greenfield Village, were picking up pace. The Greenfield Village team was looking forward to a challenging but exciting year, with a calendar full of exciting new projects.

It's not only about the new stuff, though. We all looked forward to our tried-and-true favorites coming back to life for another season: Firestone Farm, Daggett Farm, Menlo Park, Liberty Craftworks and the calendar of special events, to name a few. Each of these has a special place in our hearts and offers its own opportunities for new learning and perspectives. Despite all our hope and anticipation for this coming year, however, our plans took a different direction.

As our campus closed this past March, it had long been obvious that the year was going to be very different than the one we had planned. The Henry Ford's leadership quickly assessed the daily operations in order to narrow down to essential functions. For most of Greenfield Village, this meant keeping what had been closed for the season closed. Liberty Craftworks, which typically continues to produce glass, pottery and textile items through the winter months, was closed, and the glass furnaces were emptied and shut down. This left the most basic and essential work of caring for the village animals to continue.

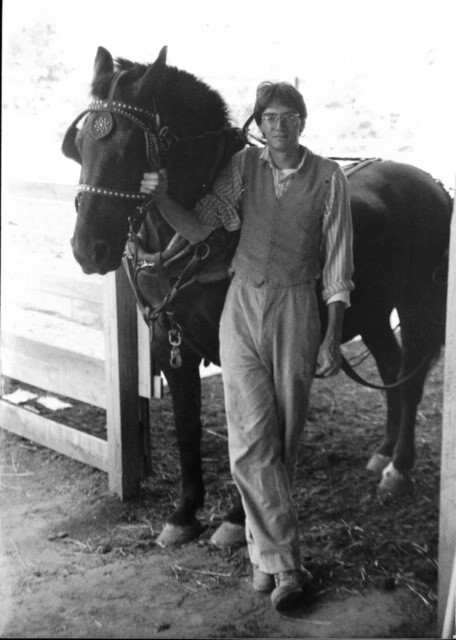

Here I am with the Percheron horse Tom at Firestone Barn, summer 1985.

As proud as I am to be director of Greenfield Village, I am equally proud, if not more so, to be part of a small team of people providing daily care for its animals. This work has brought me full circle to my roots as a member of the first generations of Firestone Farmers 35 years ago. It’s amazing to me how quickly the sights, sounds and smells surrounding me in the Firestone Barn bring back the routines I knew so well so long ago. I am also proud of my colleagues who work along with me to continue these important tasks.

The pandemic has not stopped the flow of the seasons and daily life at Firestone Farm. Our team made the decision very soon after we closed to move the group of expecting Merino ewes off-site to a location where they could have around-the-clock care and monitoring as they approached lambing time in early April. This group of nearly 20 is now under the watchful eye of Master Farmer Steve Opp in Stockbridge, Michigan, about 60 miles away.

Meet the newest members of the Firestone Farm family.

After their move, the ewes were given time to settle into their new temporary home. They were then sheared in preparation for lambing, as is our practice this time of year. I am very pleased to report that the first lambs were born Easter weekend, Saturday, April 11. All are doing well, and several more lambs are expected over the next few weeks. Once the lambs are old enough to safely travel, and we have a better understanding of our operating schedule looking ahead, they will all return to Firestone Farm, having the distinction of being the first group of Firestone lambs not born in the Firestone Barn in 35 years.

The last of the Firestone Farm sheep getting sheared in the Firestone Barn.

The wethers, rams and yearling ewes that remain at Firestone Farm were also recently sheared and are ready for the warm weather. One of the wethers sheared out at 18 pounds of wool, which will eventually be processed into a variety of products that are sold in our stores.

Continue Reading

farms and farming, farm animals, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, by Jim Johnson, Greenfield Village, COVID 19 impact

Exposing the Collections Storage Building

This blog post is part of an ongoing series about storage relocation and improvements that we are able to undertake thanks to a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

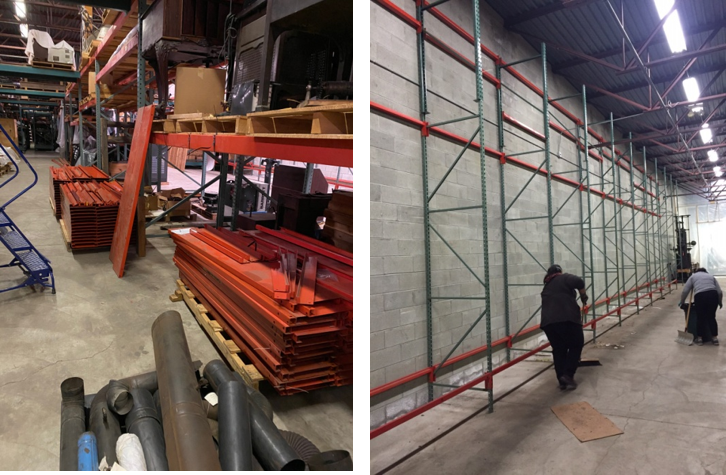

A typical aisle in the Collections Storage Building before object removal.

Autumn of this year marks the end of a three-year IMLS-funded grant project to conserve, house, relocate and create a fully digital catalogue record for over 2,500 objects from The Henry Ford’s industrial collections storage building. This is the third grant THF has received from IMLS to work on this project. As part of this IMLS blog series, we have shown some of the treatments, digitization processes and discoveries of interest over the course of the project. Now, we’d like to showcase the transformation happening in the Collections Storage Building (CSB).

A view of the aisle and southwest wall before dismantling to create a Clean Room.

Objects were removed from shelves allowing an area in the storage building to be used as a clean space for vacuuming and quickly assessing the condition of these objects before heading to the conservation lab. Since the start of the grant in October 2017, 3,604 objects have been pulled from CSB shelves along with approximately 1,000 electrical artifacts and 1,100 communications objects from the previous two grants. As of mid-March 2020, 3,491 of those objects came from one aisle of the building. As a result, we were finally at a point of taking down the pallet racking in this area.

Pallets of dismantled decking and beams. A bit of cleaning before racking removal.

While it has taken multiple years to move these objects from the shelves, it took only three days to disassemble the racking! Members of the IMLS team first removed the remaining orange decking. On average, there were four levels of decking, separated in three sections per level. Next, we unhinged the short steel beams that attach the decking to the racking. Then was the difficult part of Tetris-style detachment of the long steel beams directly by the wall from the end section of height-extended, green pallet racking. As you can see this pallet racking almost touches the ceiling! After that, the long beams could be completely removed before taking down the next bay. Nine bays were disassembled this time to reveal the concrete wall and ample floor space. Just as the objects needed cleaning to remove years of dust and dirt, so did the floor!

The aisle in 2018. An open wall and floor!

What’s next? We will methodically continue pulling objects and taking down racking until no shelf is left behind! We are grateful to the IMLS for their continued support of this project and will be back for future updates.

Marlene Gray is the project conservator for The Henry Ford's IMLS storage improvement grant.

21st century, 2020s, 2010s, IMLS grant, collections care, by Marlene Gray, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

History of the J.R. Jones General Store

J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, 2001 (THF138628)

The Waterford Country Store—as it was initially called in Greenfield Village—was the first building to arrive in the Village. Re-erected on the Village Green in 1927-28, it was soon joined by other buildings—a schoolhouse, courthouse, tavern, town hall, and chapel—that to Henry Ford all symbolized America’s spirit of community. New research in the 1990s revealed that, between the time the store was built in 1856-57 and the time Henry Ford brought it to Greenfield Village in the 1920s, nine different storekeepers had operated a general store out of this building. A reinstallation of the building in the 1990s refocused the store’s furnishings and interpretation on the era of 1882 to 1888—when J.R. Jones ran the store in Waterford, Michigan.

Store Interior, 1925 (THF69132)

This is an interior view of the stocked, fully functional store in 1925, when the August Jacober family operated it in Waterford, Michigan. The Jacobers were the last family of proprietors to run this store before it was brought to Greenfield Village.

Store exterior, 1926 (THF126117)

This photograph depicts the general store in Waterford, Michigan, just before it was removed to Greenfield Village in 1926. According to Jacober family descendants, this store was raised on skids in the street because the family was building a new brick store on its original site. Ford likely saw the old store, had his agents arrange to purchase it around August 1927, and then had it moved to Greenfield Village.

Store exterior in Greenfield Village, 1958 (THF138605)

When Henry Ford first envisioned a Village Green as the centerpiece of his recreated village in Dearborn, the general store was situated and reconstructed on what would become its permanent location. The Elias Brown sign that hangs out front in this 1958 image came from upstate New York. During this time, the store was known as the Elias Brown General Store.

Store interior in Greenfield Village, 1965 (THF126771)

To furnish the building with authentic general store artifacts from the past, Ford sent agents in search of unsold stock that might still remain in old general stores. Their finds primarily came from stores in upstate New York and New Hampshire. By the 1960s, as seen in this image, the interior was furnished not only with old store stock but also with penny candy that visitors could purchase.

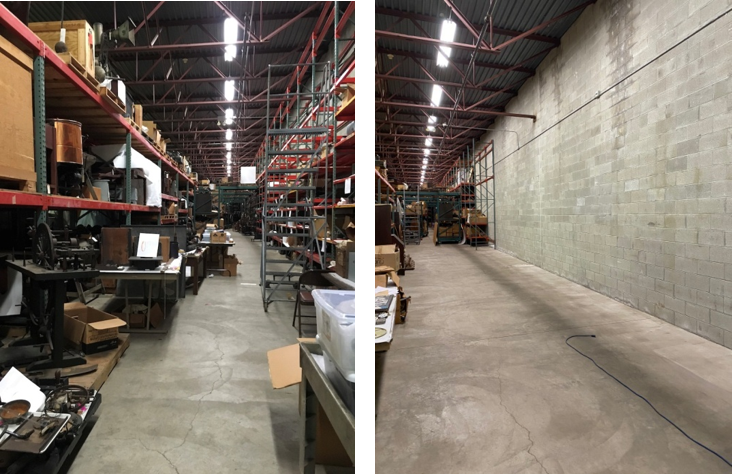

Store exterior, 1994, with vintage Lah-de-Dahs baseball team posing in front (THF136301)

Research in the 1990s led to a new, more accurate historical interpretation of this store as it existed in Waterford, Michigan, during the 1880s. This era was chosen to represent a transition in stores—from old-fashioned displays of pickle barrels and flour bins to shelves stocked with more modern products like canned goods and brand-name items. A new sign with the name of the proprietor of this store in Waterford during the 1880s—J.R. Jones—replaced the old Elias Brown sign over the front entrance.

Store interior, 2008, with historically-dressed presenter (THF53771)

Use of period photographs, account books, and inventories led to the choices of stock for the store. Presenters in this building—dressed in accurately-researched historic clothing—tell the stories of J.R. Jones, the customers who shopped here in the 1880s, and the products they might have purchased.

Donna Braden is Senior Curator and Curator of Public Life at The Henry Ford.

shopping, 20th century, 19th century, Michigan, J.R. Jones General Store, Greenfield Village history, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, entrepreneurship, by Donna R. Braden, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 2010s

As the 21st century began, The Henry Ford’s automotive exhibit, Automobile in American Life, was into its second decade of life, and needed a refresh. In a major change that affected 80,000 square feet on the Museum floor, Driving America roared into life in January of 2012.

Not only were the themes and artifacts included in the exhibit completely rethought, but digital technologies were integrated from the beginning to fuel touchscreen kiosks containing activities, curator interviews, and tens of thousands of digitized artifacts from The Henry Ford’s collections—including a substantial new set of glamour shots for each vehicle in the exhibit. This first big experiment with digitized collections within an exhibit is forming the basis for the use of interactive technologies in upcoming exhibits.

Technology Accelerates at the Rouge

In late 2014, Ford Motor Company began producing the first mass-produced truck in its class featuring a high-strength, military-grade, aluminum-alloy body and bed after having completely redesigned its F-150 assembly line at the Ford Rouge plant. This posed a challenge for the Ford Rouge Factory Tour—the manufacturing story had completely changed. An overhaul of the entire experience involved updated experiences in both theaters, particularly in the Manufacturing Innovation Theater, offering a multisensory, multidirectional show. An interactive kiosk, similar to those installed in Driving America, was also installed to allow visitors to access The Henry Ford’s digital collections with the touch of a finger.

Village Growth

While the Village has not yet seen any more changes as substantial as those that occurred in the early part of the 21st century, the period since 2010 has brought a couple of notable upgrades to the working districts of Greenfield Village. One was the 2014 addition of a 50-foot-tall coaling tower, based on historic designs and used to store and load coal into the historic operating locomotives of Greenfield Village.

The other recent project was the physical expansion of the Pottery Shop in 2013, a project sparked by the need to replace a salt kiln that was nearly three decades old. The kiln room was rebuilt and slightly expanded, and by reconfiguring the layout, a spacious area for the decorators to work was also created.

Anniversaries and Remembrances

Despite the growth in digital experiences, the power of physical artifacts is still undeniable. Many significant anniversaries related to the objects and stories of The Henry Ford have been observed with events within Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in recent years.

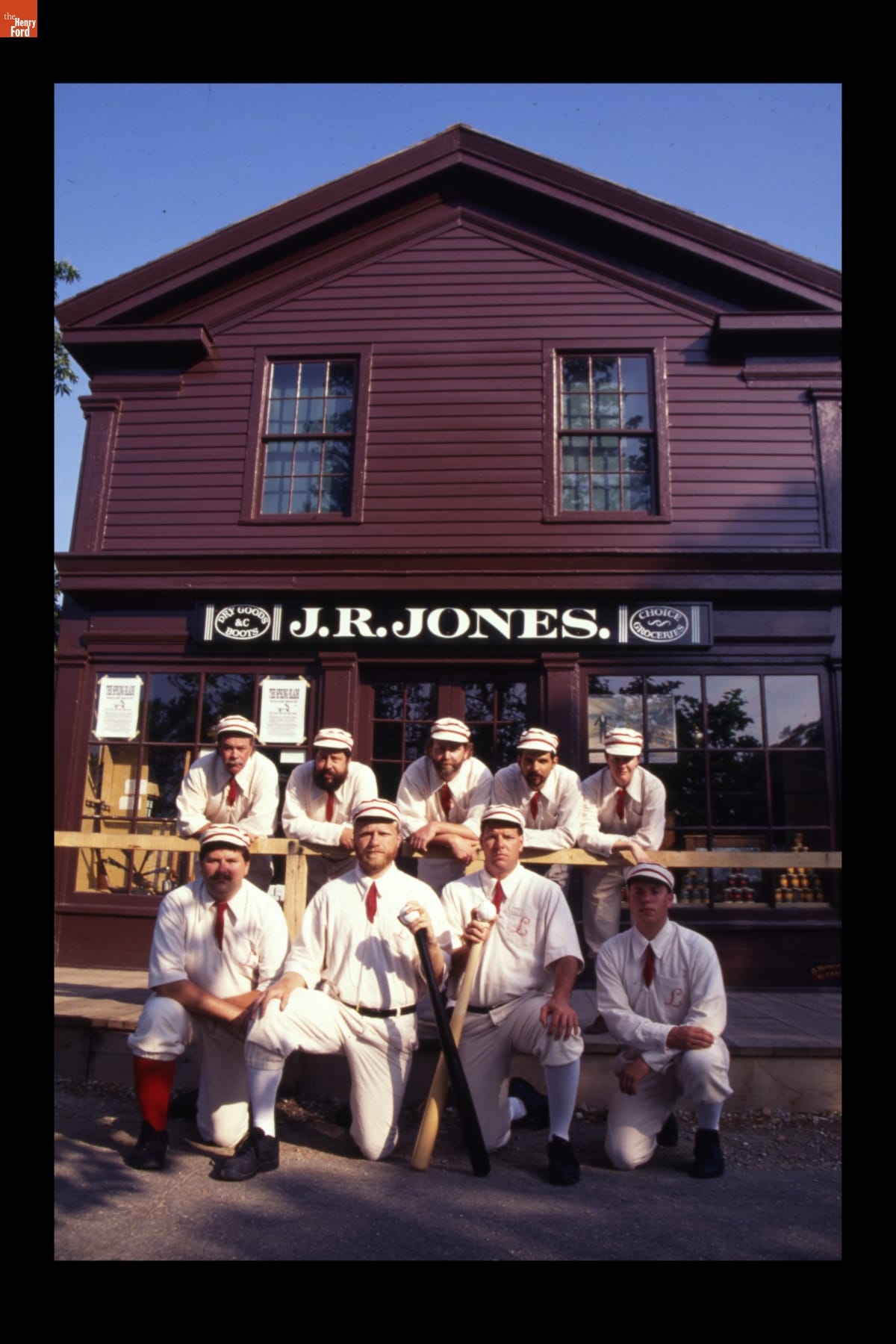

One of the largest and most notable was the Day of Courage, celebrated with an all-day event on February 4, 2013. Historians, musicians, students, and Museum guests remembered the life of Rosa Parks on her 100th birthday. In November 2013, lectures by newscaster Dan Rather and former Secret Service agent Clint Hill, as well as an opportunity to visit the fateful limousine, formed a remembrance of President John F. Kennedy on the 50th anniversary of his assassination. April 2015, the 150th anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, was marked with a lecture by historian Doris Kearns Goodwin and the first removal of the Lincoln chair from its display case in decades.

Innovation Focus

Our collecting continues to focus on resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity—and both new and old artifacts, along with their stories, are featured in new ways. In particular, as digital technologies became ubiquitous, The Henry Ford began developing new strategies to accomplish its mission to share, teach, and inspire, particularly focused on the “innovation” portion of the mission statement.

The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ represents the core assets of The Henry Ford that illustrate the process and context of innovation. It refers to artifacts and documents in the collection that provide an unprecedented window into America’s traditions of resourcefulness, innovation, and ingenuity. It is the key to understanding how our entire modern world was created.

Related stories of artifacts and innovation are featured on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation, a weekly educational TV program produced by Litton Entertainment and hosted by Mo Rocca, which has aired since Fall 2014. Innovation is also brought in through events such as Maker Faire Detroit, hosted annually at The Henry Ford since 2010.

Active Collecting

Though the world has become increasingly digital, The Henry Ford continues to collect hundreds or even thousands of physical artifacts each year. In the second decade of the 21st century, this has included material related to significant artifacts we already hold (John F. Kennedy material, to add additional context to the Kennedy Limousine; and the George Devol collection, which relates to the world’s first industrial robot), design (an Eames-designed, IBM-used kiosk and hundreds of examples of 20th century soap packaging), and auto racing (photographic collections from John Clark and Ray Masser and dozens of tether cars or “spindizzies”).

Major recent acquisitions include the John Margolies Roadside America collection, the Bachmann studio collection of American glass, the Roddis clothing collection, and Mathematica, a circa 1960 exhibit designed by Charles and Ray Eames.

The Collections Go Digital

The Henry Ford began scaling up its collections digitization effort in 2010, hiring new staff with new skills to advance this technology-intensive effort that involves conservation, cataloging, photography, and scanning. Images of tens of thousands of artifacts are now freely available online, from our Digital Collections, and provide the basis for additional layers of supporting content, helping the public to understand artifacts in the context of their original time and place as well as the context of today.

Digitization efforts include artifacts on display within the Museum or Village, new acquisitions, and “hidden” items currently in storage. In 2013–15, for example, more than 1,200 communications-related artifacts in storage, including many significant rediscovered treasures, were digitized through a grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services (IMLS).

From Digital Artifacts to Digital Stories

While more than 20,000 artifacts are on public exhibit in Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, the Benson Ford Research Center, and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, The Henry Ford’s collection holds many more—about 250,000 objects and millions more photographs and documents within our archives. Institutional commitment to the digitization of The Henry Ford Archive of American Innovation™ is making these collections, and the ideas behind them, more accessible to more people in more ways than ever.

Acquisitions Made to the Collections - 2010s

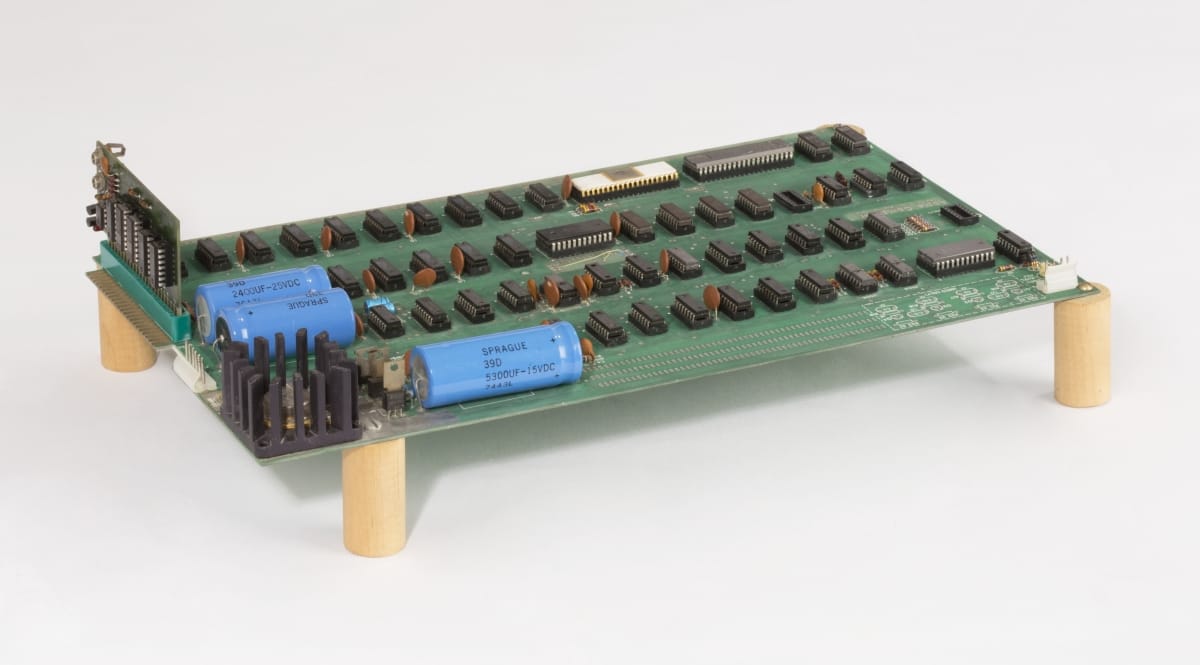

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

In 2013, The Henry Ford acquired an Apple 1 computer—one of the first fifty ever made, and fully operational. This groundbreaking device documents an important “first,” as one of the earliest desktop computers to be sold with a pre-assembled motherboard (although users had to purchase a separate keyboard, monitor, and power source). The Apple 1 is also the beginning of something in the sense that it led to the founding of one of today’s most successful computer companies in the world. This artifact demonstrates The Henry Ford’s commitment to collecting the hardware, software, and the ephemeral culture that powers the digital age. You can see a video describing the Apple 1 acquisition and the process of booting it up here. - Kristen Gallerneaux, Curator of Communication & Information Technology

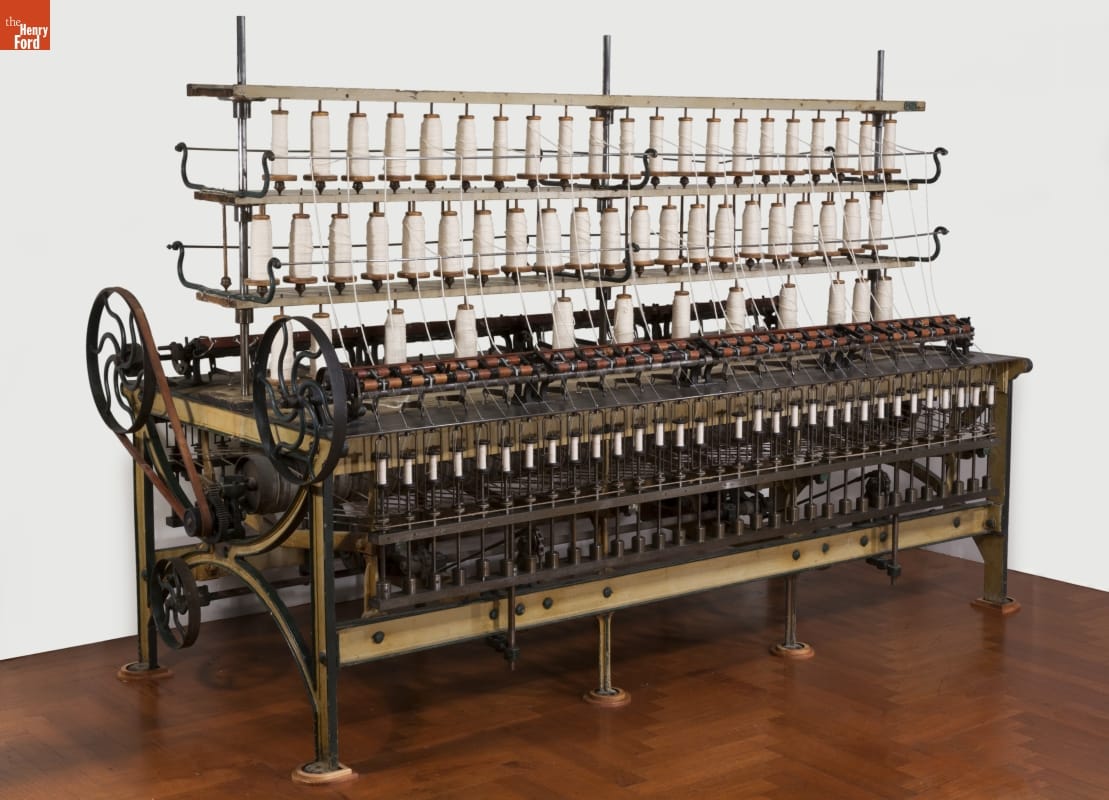

Throstle Spinning Frame

This rare spinning frame was part of a landmark acquisition, perhaps the largest since Henry Ford’s time--nine truckloads of textile history-related objects and archival materials! Spinning frames like this circa 1835 example--likely the earliest surviving American industrial textile machine--helped spin the large quantities of thread that growing industrial weaving operations needed in the early and mid-19th century. In 2016, the American Textile History Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts closed its doors and began to transfer their collections to other organizations. The Henry Ford was among them--able to provide a home for many thousands of objects dating from the 18th to 21st centuries: textile machinery and tools, clothing and domestic textiles, and hundreds of sample books of printed fabrics from several major New England companies. This rich collection from ATHM tells the story of a key player in America’s Industrial Revolution--the textile industry. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

La-Z-Boy Reclina Rocker

La-Z-Boy is a story of technological innovation, marketing, and sales savvy. Two cousins created the first chair in the late 1920s but didn’t gain acclaim until the 1960s with the Reclina Rocker, which combined a built-in ottoman with a rocking feature. Multi-faceted promotional strategies, including celebrity endorsements, caught the eye of middle-class Americans, who eagerly bought the chair for their homes. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

2016 General Motors First-Generation Self-Driving Test Vehicle

Self-driving cars have the potential to reduce accidents, ease traffic, reduce pollution, and improve mobility for people unable to drive themselves. Assuming we can solve the remaining technical, legal, and psychological challenges, autonomous cars promise to bring the most significant change in our relationship with the automobile since the Model T itself. This experimental vehicle represents General Motors' first major step toward our autonomous future -- and The Henry Ford's first major step to document the journey. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

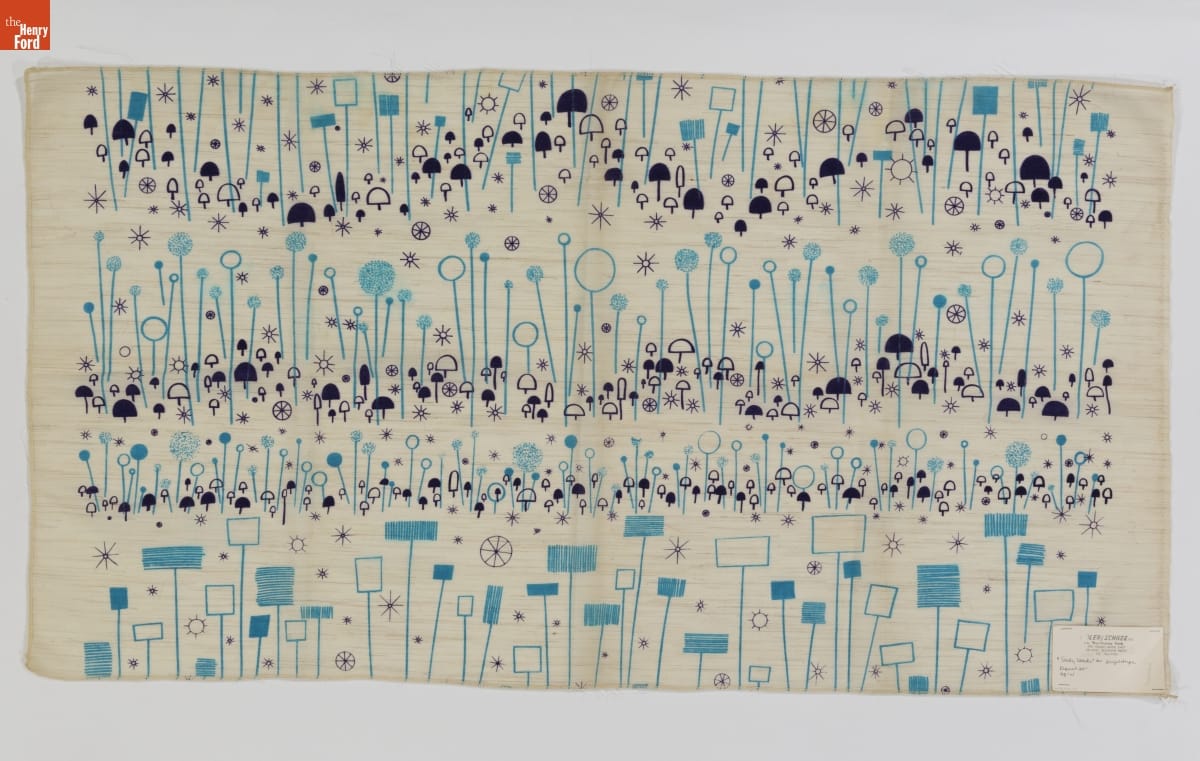

Ruth Adler Schnee Textiles

Designer Ruth Adler Schnee's modern textiles are bold, colorful, and pushed the mid-20th century modern design movement forward. She drew inspiration from the world around her, the ordinary as well as the extraordinary. The Henry Ford's acquisition of her textiles in 2000 and in 2018 speak to her continued relevance to our collection-- as a modern design pioneer, a female entrepreneur, and a Jewish immigrant. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

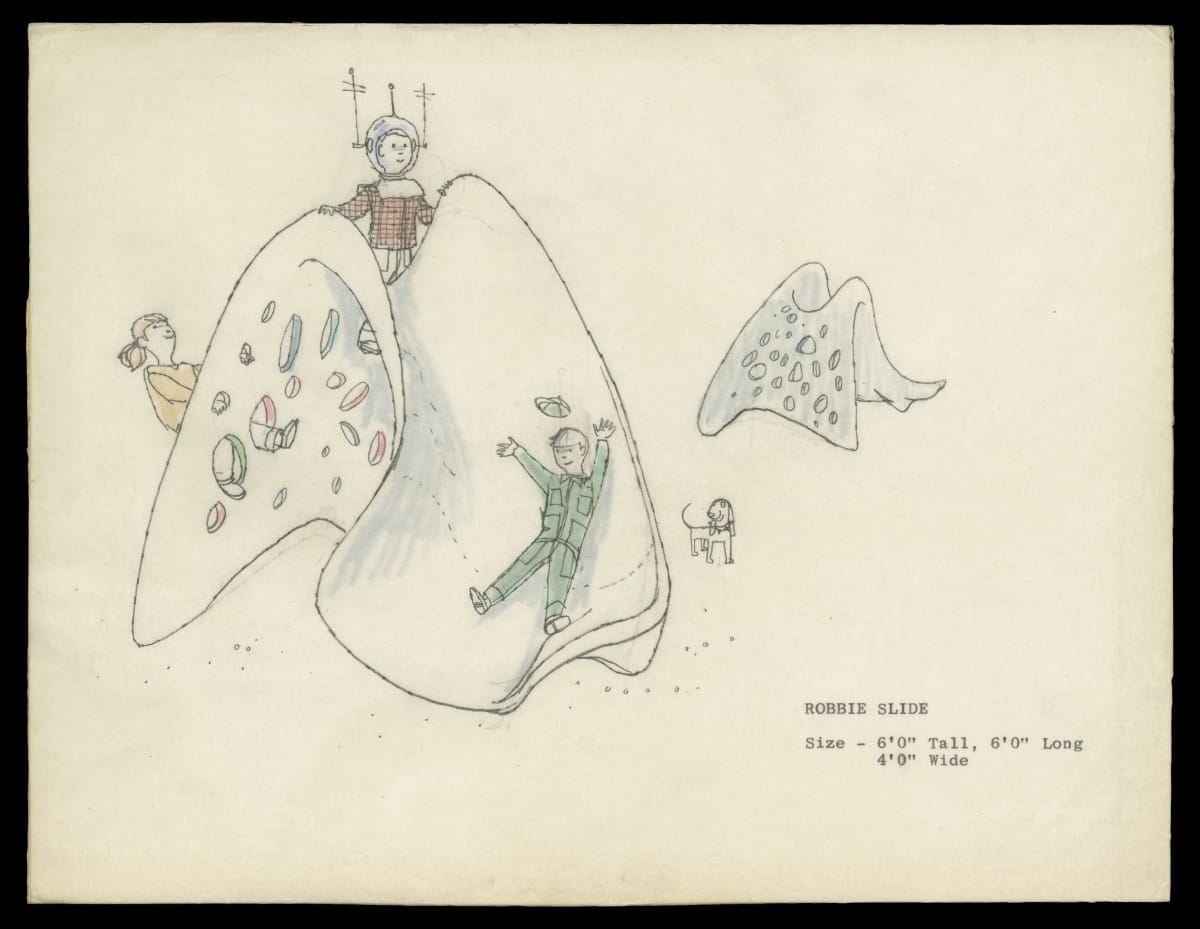

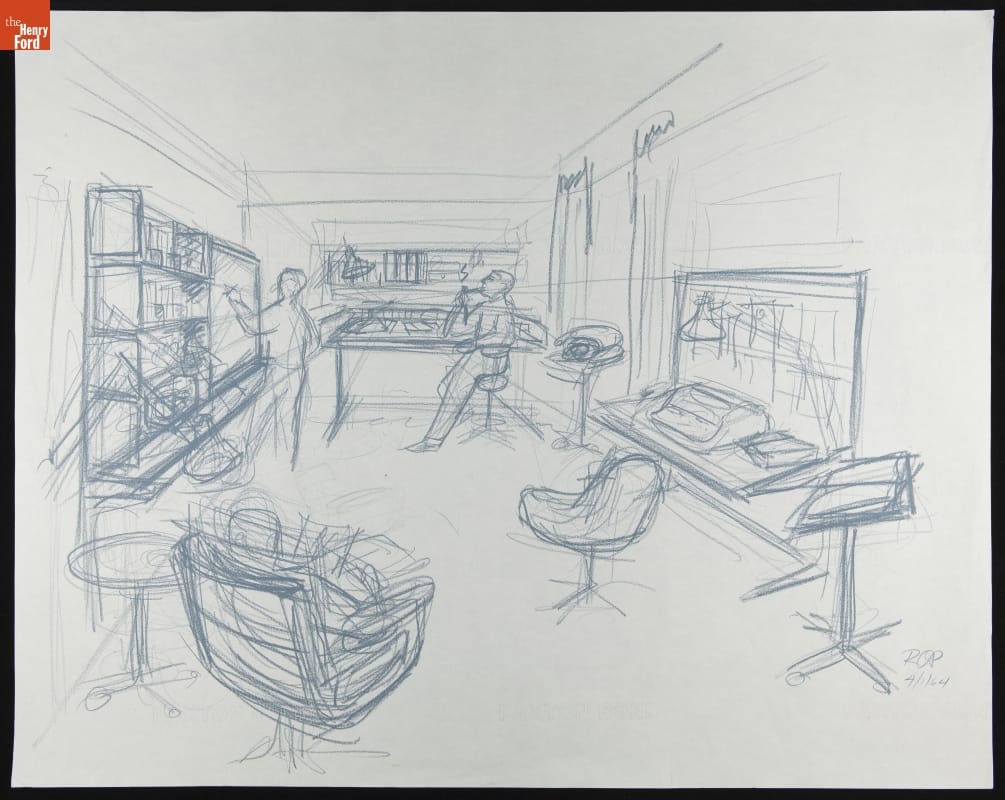

Robert Propst Papers

Noted industrial designer Robert L. Propst is best known for his work with Herman Miller and for designing the “Action Office,” an office furnishing system which became the basis for the modern cubicle. Propst’s papers cover the design and business aspects of “Action Office” as well many of his other projects such as a residential housing system, hotel housekeeping carts, hospital furniture, an industrial timber harvester, and even children's playground equipment. - Brian Wilson, Sr. Manager, Archives and Library

Champion Egg Case Machine, 1900-1925

This artifact furthers The Henry Ford's mission in several ways –it’s the product of an innovator. James Ashley first patented a box-making machine in 1892. Resourceful farm families with eggs to sell built boxes with this machine, marked the contents "farm fresh," and shipped their product to meet the growing demand of chicken-less urban consumers. The machine created a standardized box which held 12 flats (six on each side). Each flat held 30 eggs for a total of 360 eggs (30 dozen) in one box. Consumers today eat eggs transported to market on flats in boxes similar to the ones this machine was designed to build. Ashley's egg-case maker helps document the long history of farm-market exchange that responded to wary consumers' concerns over the freshness of the agricultural product. - Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

events, Ford Rouge Factory Complex, Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345

Westinghouse Portable Steam Engine No. 345, Used by Henry Ford. THF140104

In 1882, 19-year-old Henry Ford had an encounter with this little steam engine that changed his life. Though initially unsure of his abilities, he served as engineer, overseeing the maintenance and safe operation of the engine for a threshing crew organized by Wayne County, Michigan farmer John Gleason. He went on to run the engine for the rest of the season, developing the skills and knowledge of an experienced engineer. This assured Henry Ford that machines--not farming--were his future.

Pictured here with the steam engine are (left-to-right) Hugh McAlpine, James Gleason, and Henry Ford. This photograph was taken in 1920 on the Ford Farm in Dearborn. THF199289

Henry Ford never forgot this engine. Three decades later, as head of the world’s largest automobile company, he set out to find it again, sending representatives out scouring the countryside looking for the Westinghouse steam engine, serial number 345. Finally, one of his men found it in a farmer’s field in Pennsylvania. In 1912, Henry Ford purchased it from Carrolton R. Hayes, and had it completely rebuilt. Thereafter, Henry ran it regularly, often in the company of James Gleason, the brother of the man who originally bought it.

Read more content related to The Henry Ford's 90th anniversary here.

Additional Readings:

- Power by the Quarter

- Looking Back to Move Forward

- 1927 Plymouth Gasoline-Mechanical Locomotive

- Electrical Connection

Henry Ford Museum, farms and farming, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, engineering, engines, power, Henry Ford

How We Do It: Costuming Our Hallowe'en Characters

The costumes featured in Hallowe’en at Greenfield Village are made for all types of weather conditions. Just like trick-or-treaters walking through their own neighborhoods on October 31, our presenters and staff members must be ready for any weather scenario.

Try these tips from our costuming experts in our Period Clothing Studio.

Our Hallowe’en costumes are made of a water resistant, breathable, nylon athletic material called Supplex, so that they can be worn in the rain. When that material isn’t used, our lightweight cottons are sprayed with Scotchguard or have a wool outer layer that naturally protects the wearer. If you purchase a costume made of thin polyester, make sure you can layer a windbreaker or waterproof athletic shirt underneath for rainy weather. Most of the characters during Hallowe’en also have umbrellas that match their outfits in case rain is in the forecast.

When the temperatures are warmer than normal, our costumes are built to be worn over lightweight cotton layers, like T-shirts and shorts or leggings to wick away sweat. Conversely, thermal underlayers can be added for cold weather to add protection without added bulk.

Need a Greenfield Village example? The Lion costume is worn over cotton layers with an ice pack vest to keep the presenter cool in the heat. The vest is not worn during cold weather.

Some of our costumes have additional overlayers for very cold weather, but they are built into the design. For example, the Mermaid has a separate bodice lined in wool to be worn over the sequin-and-net bodice of the dress, and has earmuffs decorated with hair wefts to look as though they are a part of her wig.

Don’t forget - wear comfortable, waterproof, slip-resistant shoes, just like us. You can always cover sneakers with spats or ice skate covers to match your costume.

Visibility is key when it comes to creating a costume. Many of our costumes feature waterproof lighting which can be an added safety feature for costumes worn in the dark. We use decorative fairy lights, like those used for special outdoor events, which have waterproof battery packs. The lighting is sewn into channels under a sheer decorative layer or tacked into the costume with the battery packs easily accessible at the waistband.

If you are wearing a mask, practice wearing it in low lighting before wearing it outside. You can cut away the eye holes in plastic masks or extend your peripheral vision by swapping out sheer jersey eye holes in soft masks with tulle or net and use makeup around your eyes to disguise the transition.

Halloween costumes and accessories don’t have to be brand new. Try repurposing and upcycling old clothing by dyeing it and then adding trim to give texture. This year our female pirate costumes are repurposed 18th century dresses from stock that were dyed, altered, and trimmed to fit the theme. A past mermaid costume net cape was repurposed as trim in the yellow ochre pirate’s dress by dyeing it and stitching it to the peplum to create texture.

Is your costume’s color not quite right or the fabric can’t be dyed? Try using fabric paint and a sponge to gently tone down the color. The Bad Fairy wings were originally a bright green metallic lace, but we sponge painted over the material with emerald green, spruce green, and navy fabric paints to create a darker ombre effect to match the rest of the costume. But watch that paint - some must be heat set, while others can take 24-48 hours to fully dry.

Still looking for costume inspiration? Try taking a stroll down our pumpkin-lit path this month during Hallowe’en in Greenfield Village. You never know which character may ignite the Halloween maker in you.

Anne Suchyta Devlin is Senior Manager of the Studio at The Henry Ford.

making, holidays, Hallowe'en in Greenfield Village, Halloween, Greenfield Village, fashion, costumes, by Anne Suchyta Devlin, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Robert O. Derrick, Architect of Henry Ford Museum

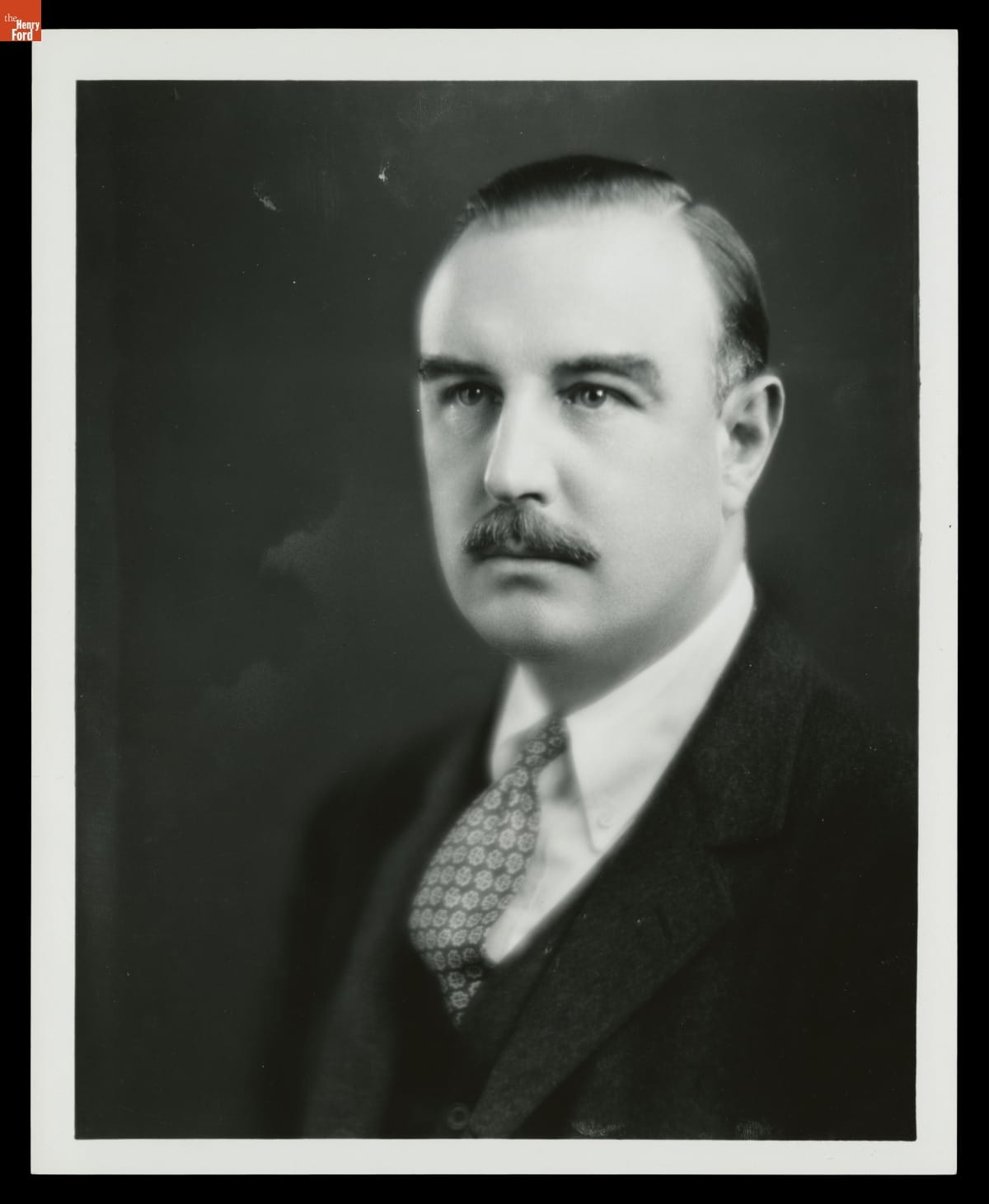

Robert O. Derrick, about 1930. THF 124645

As part of our 90th anniversary celebration the intriguing story of Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation’s design bears repeating. It was last discussed in depth in the 50th anniversary publication “A Home for our Heritage” (1979).

Our tale begins on the luxury ocean liner R.M.S. Majestic, then the largest in the world, on its way to Europe in the spring of 1928. On board were Henry and Clara Ford, their son Edsel and Edsel’s wife Eleanor. Serendipitously, Detroit-based architect Robert O. Derrick and his wife, Clara Hodges Derrick, were also on board. The Derricks were approximately the same age as the Edsel Fords and the two couples were well-acquainted. According to Derrick’s reminiscence, housed in the Benson Ford Research Center, he was invited by Henry Ford to a meeting in the senior Fords’ cabin, which was undoubtedly arranged by Edsel Ford. During the meeting Derrick recalled that Mr. Ford asked how he would hypothetically design his museum of Americana. Derrick responded, “well, I’ll tell you, Mr. Ford, the first thing I could think of would be if you could get permission for me to make a copy of Independence Hall in Philadelphia. It is a wonderful building and beautiful architecture and it certainly would be appropriate for a collection of Americana.” Ford enthusiastically approved the concept and once back in Detroit, secured measured drawings of Independence Hall and its adjacent 18th century buildings which comprise the façade of the proposed museum. Both Derrick and Ford agreed to flip the façade of Independence Hall to make the clock tower, located at the back side of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, a focal point of the front of the new museum in Dearborn.

Robert Ovens Derrick (1890-1961) was an unlikely candidate for the commission. He was a young architect, trained at Yale and Columbia Universities, with only three public buildings to his credit, all in the Detroit area. He was interested in 18th century Georgian architecture and the related Colonial Revival styles, which were at the peak of their popularity in the 1920s.

In his reminiscence, he states that he was overwhelmed with the commission, but was also confident in his abilities: “I did visit a great many industrial and historical museums and went to Chicago. I remember that I studied the one abroad in Germany, [The Deutsches Museum in Munich] which is supposed to be one of the best. I studied them all very carefully and I did make some very beautiful plans, I thought. Of course, I was going according to museum customs. We had a full basement and a balcony going around so the thing wouldn’t spread out so far. We had a lot of exhibits go in the balcony. I had learned that, in museum practice, you should have a lot more storage space, maintenance space and repair shops than you should have for exhibition. That is why I had the big basement. I didn’t even get enough there because I had the floor over it plus the balconies all around.”

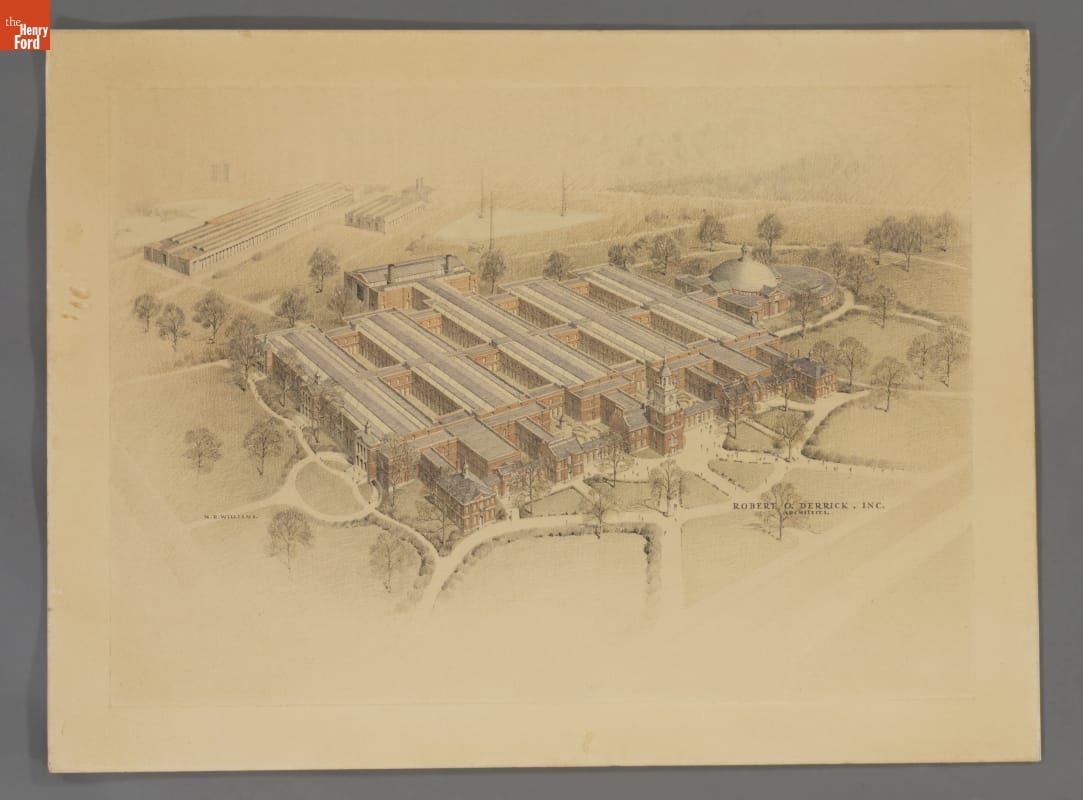

Original museum proposal, aerial view. THF 170442

Original museum proposal, facade design. THF 170443

Original museum proposal, side view. THF 170444

In the aerial view [THF0442], the two-story structure is a warren of courtyards and two-story buildings, with exhibition space on the first floor and presumably balconies above, although no interior views of this version survive. A domed area on the upper right was to be a roundhouse, intended for the display of trains. THF0443 shows a view of the front of the museum from the southeast corner. This view is close to the form of the completed museum, at least from the front. An examination of the side of the building [THF0444] shows a two-storied wing.

Derrick recalled Mr. Ford’s initial response to his proposals, “What’s this up here? and I said, that is a balcony for exhibits. He said, I wouldn’t have that; there would be people up there, I could come in and they wouldn’t be working. I wouldn’t have it. I have to see everybody. Then he said: What’s this? I said, that is the basement down there, which is necessary to maintain these exhibits and to keep things which you want to rotate, etc. He said, I wouldn’t have that; I couldn’t see the men down there when I came in. You have to do the whole thing over again and put it all on one floor with no balconies and no basements. I said, okay, and I went back and we started all over again. What you see [today] is what we did the second time.” Henry Ford Museum proposed Exhibit Hall. THF294368

Henry Ford Museum proposed Exhibit Hall. THF294368

A second group of presentation drawings show the museum as it was built in 1929. THF294368 is the interior of the large “Machine Hall,” the all-on-one-floor exhibit space that Mr. Ford requested. The unique roof and skylight system echo that of Albert Kahn’s Ford Engineering Laboratory, completed in 1923 and located just behind the museum. Radiant heating is located in the support columns through what appear to be large flanges or fins. The image also shows how Mr. Ford wanted his collection displayed – in long rows, by types of objects – as seen here with the wagons on the left and steam engines on the right.

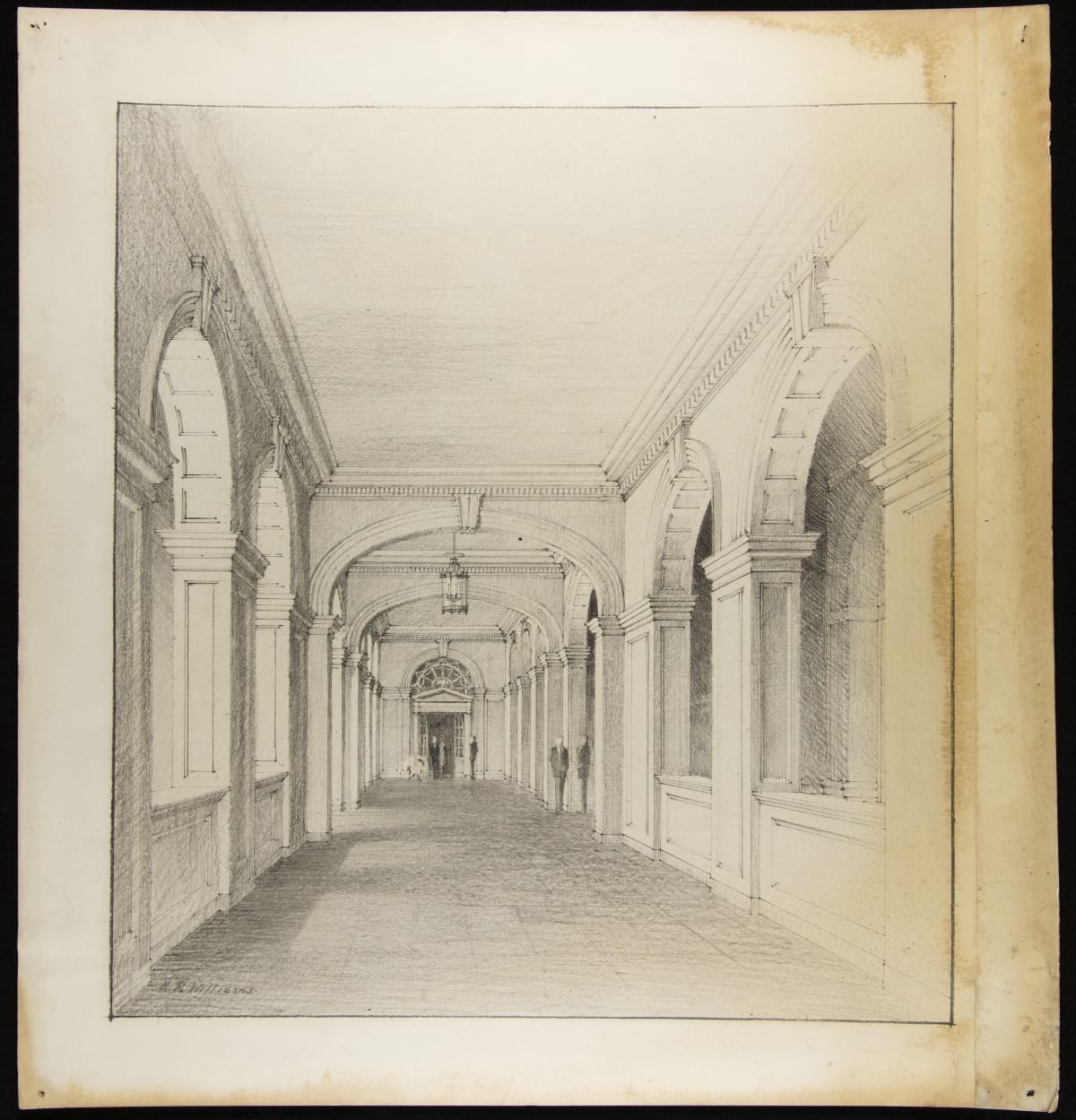

Proposal for museum corridor. THF 294390

Proposal for museum corridor. THF 294388

These corridors, known today as the Prechter Promenade, run the width of the museum. Floored with marble and decorated with elaborate plasterwork, the promenade is the first part of the interior seen by guests. Mr. Ford wanted all visitors to enter through his reproduction of the Independence Hall Clock Tower. The location of Light’s Golden Jubilee, a dinner and celebration of the 50th anniversary of Thomas Edison’s development of incandescent electric lamp, held on October 21, 1929 is visible at the back of THF294388. This event also served as the official dedication of the Edison Institute of Technology, honoring Ford’s friend and mentor, Thomas Edison. Today the entire institution is known as The Henry Ford, which includes the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation and Greenfield Village.

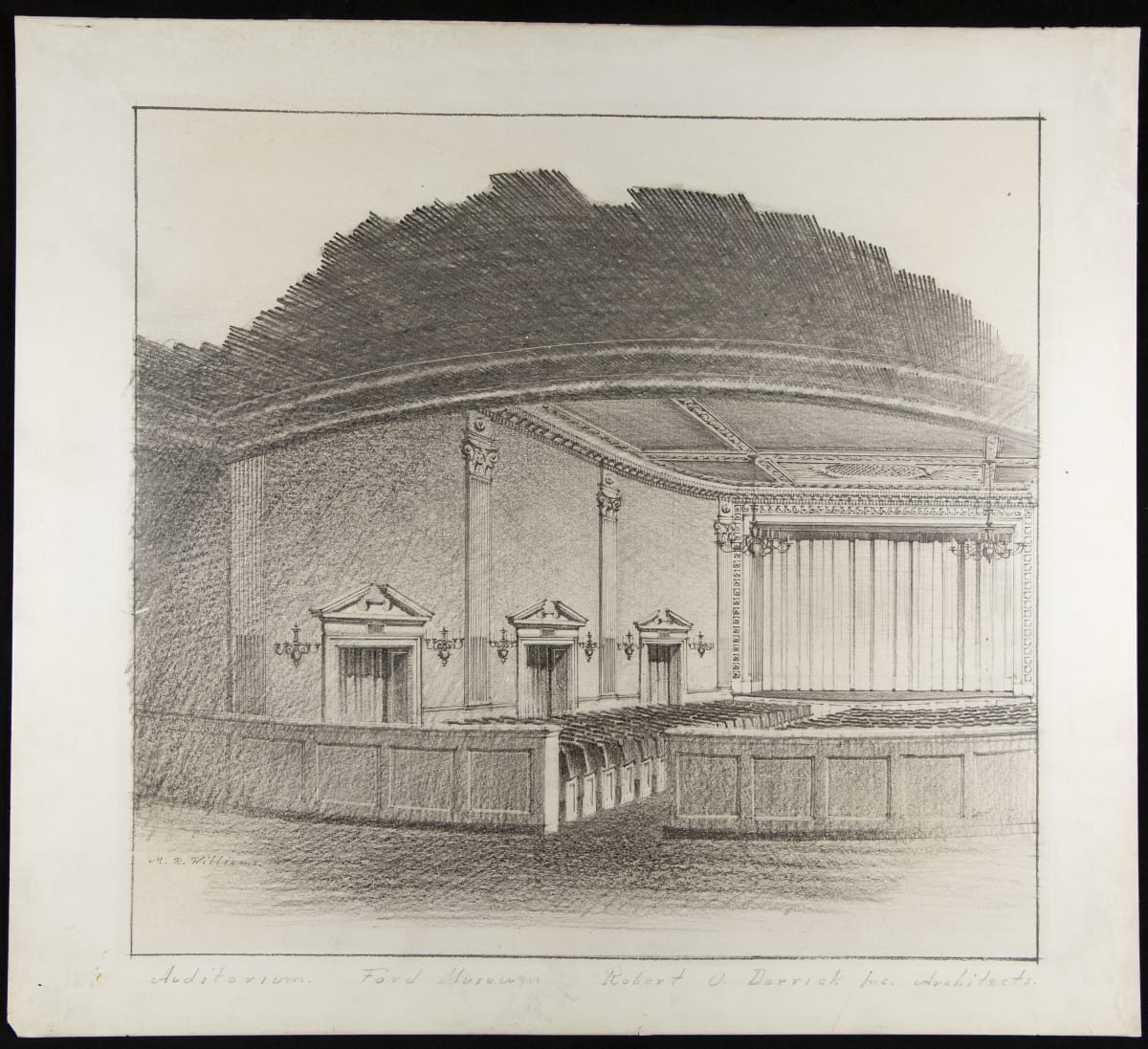

Museum Auditorium. THF 294370

Just off the Prechter Promenade is the auditorium, now known as the Anderson Theater. Intended to present historical plays and events, this theater accommodates approximately 600 guests. During Mr. Ford’s time it was also used by the Greenfield Village schools for recitals, plays, and graduations. Today, it is used by the Henry Ford Academy, a Wayne County charter high school, and the museum for major public programs.

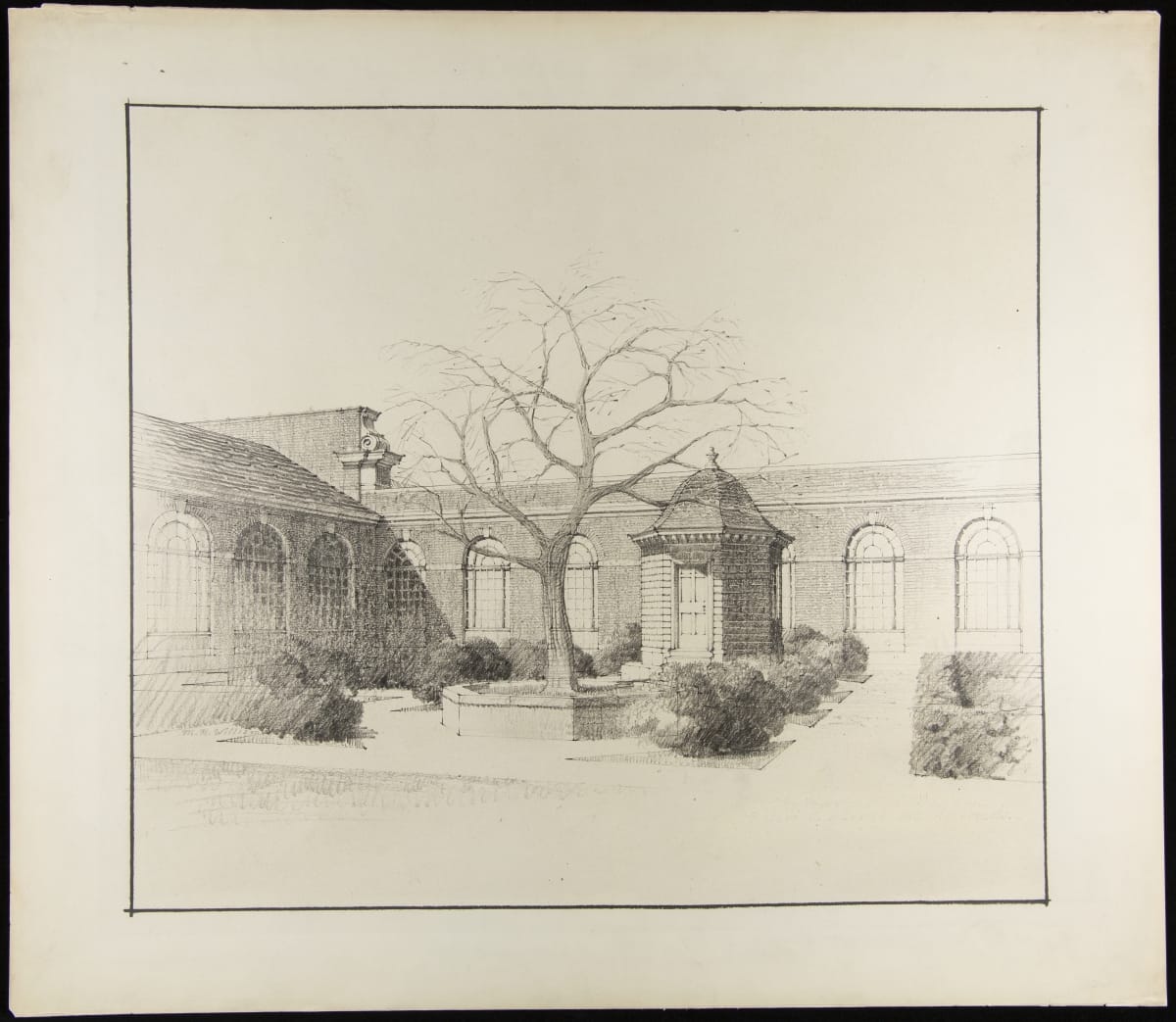

Virginia Courtyard inside Henry Ford Museum. THF294374

Pennsylvania Courtyard inside Henry Ford Museum. THF294392

Derrick created two often-overlooked exterior courtyards between the Prechter Promenade and the museum exhibit hall. Each contains unique garden structures, decorative trees and plantings, and both are accessible to the public from neighboring galleries.

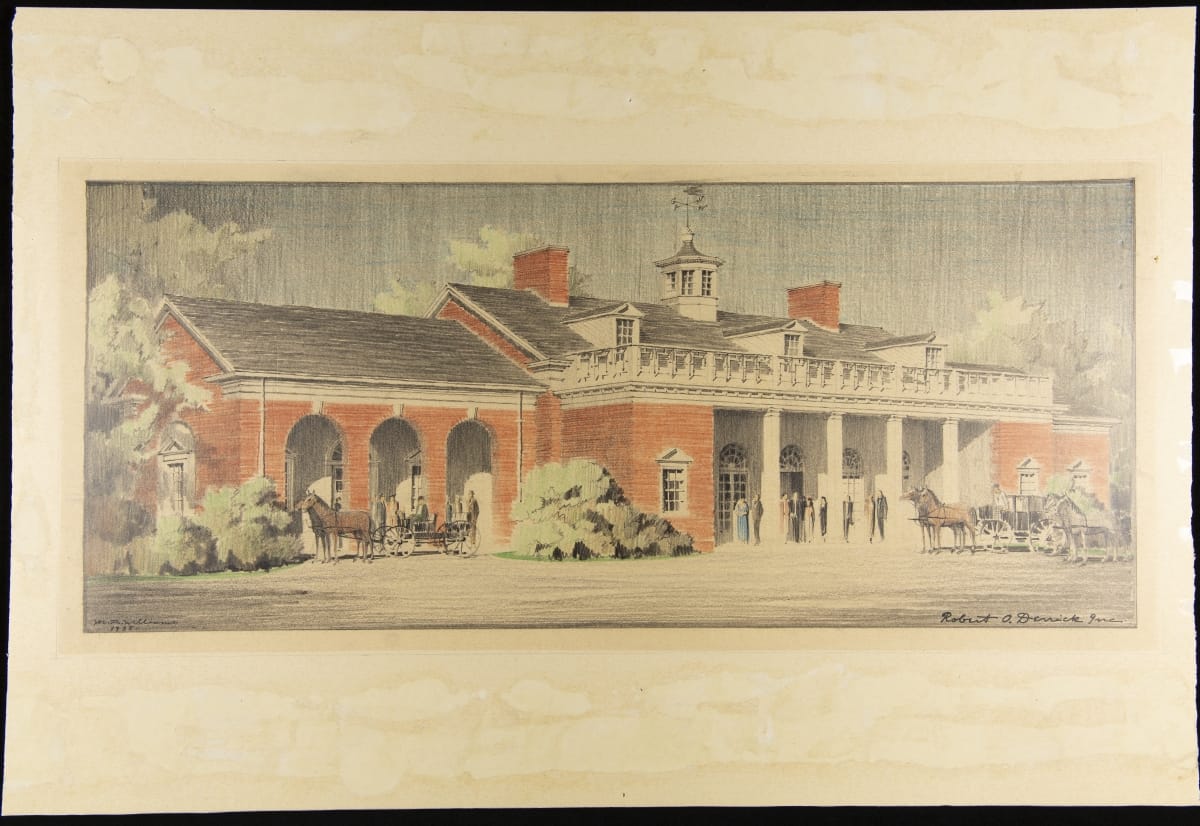

Greenfield Village Gatehouse front view, about 1931. THF 294382

Greenfield Village Gatehouse rear view, about 1931. THF 294386

The Greenfield Village Gatehouse was completed in 1932 by Robert Derrick, in a Colonial Revival style to complement the Museum. From its opening in 1932 until the Greenfield Village renovation of 2003, the gatehouse served as the public entrance to the Village. Today, visitors enter the Village through the Josephine Ford Plaza behind the Gatehouse. Although the exterior was left unchanged in the renovation, the Gatehouse now accommodates guests with an updated facility, including new, accessible restrooms and a concierge lounge with a will-call desk for tickets.

Lovett Hall in 1941. THF 98409

Edison Institute students dancing in Lovett Ballroom, 1938. THF 121724

Edison Institute students in dancing class with Benjamin Lovett, instructor, 1944. THF 116450

In 1936 Robert Derrick designed the Education Building for Mr. Ford. Now known as Lovett Hall, the building served many purposes, mainly for the Greenfield Village School system. It housed a swimming pool, gymnasium, classrooms, and an elaborately-decorated ballroom, where young ladies and gentlemen were taught proper “deportment.” Like all the buildings at The Henry Ford, it was executed in the Colonial Revival style. Today the well-preserved ballroom serves as a venue for weddings and other special occasions.

Obviously, Mr. Derrick was a favorite architect of Mr. Ford, along with the renowned Albert Kahn, who designed the Ford Rouge Factory. The museum was undoubtedly Derrick’s greatest achievement, although he went on to design Detroit’s Theodore J. Levin Federal Courthouse in 1934. Unlike the Henry Ford commissions, the courthouse was designed in the popular Art Deco, or Art Moderne style. Derrick is also noted for many revival style homes in suburban Grosse Pointe, which he continued to design until his retirement in 1956. He is remembered as one of the most competent, and one of the many creative architects to practice in 20th century Detroit.

Charles Sable is Curator of Decorative Arts at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford, Dearborn, by Charles Sable, THF90, Michigan, Henry Ford Museum, drawings, design, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 2000s

By the late 20th century, competition for the public’s leisure time was fierce and audience expectations were changing. Museum staff laid the foundation for a new generation of offerings in several distinct and separate venues—creating a unique, multi-day destination opportunity for local and out-of-town guests. These included: Henry Ford Museum, featuring a new changing exhibit gallery in 2003; Greenfield Village, refreshed and reimagined in 2003; IMAX® Theatre, opened in 1999; Benson Ford Research Center, opened in 2002; and the Ford Rouge Factory Tour, created in partnership with Ford Motor Company in 2004 and featuring a fully functioning, state-of-the-art manufacturing facility. Adding so many new venues to the museum led to a name change to encompass them all—The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford acquired its Douglas DC-3 airplane in 1975. Due to its size, the plane initially was displayed outside Henry Ford Museum. In 2002, the plane was disassembled and thoroughly conserved to correct the effects of 27 years of weather exposure. The treated DC-3 was reassembled for display inside the museum in 2003.

Bidding on History

Rosa Parks Bus in Montgomery, Alabama, 2000-2001, before Acquisition by The Henry Ford

In September 2001, an article in the Wall Street Journal announced that the Rosa Parks bus would be auctioned online in October, and we immediately began researching this opportunity.

We spoke to people involved in the original 1955 events, to those who planned other museum exhibits, and to historians. A forensic document examiner was hired to see if the scrapbook was authentic. A Museum conservator went to Montgomery to personally examine the bus.

Convinced that this was the Rosa Parks bus, we decided to bid on the bus in the Internet auction.

The bidding began at $50,000 on October 25, 2001 and went until 2:00 AM the next morning. We persevered, with our staff bidding $492,000 to outbid others who wanted the bus, including the Smithsonian Institution and the City of Denver. At the same time, our team also bought the scrapbook and a Montgomery City Bus Lines driver's uniform.

Collecting in the 2000s

Pig Pen Variation and Mosaic Medallion Quilt by Susana Allen Hunter, 1950-1955

Recent decades found curators gathering objects and stories of previously underrepresented groups. In 2006, the museum acquired 30 quilts made by African American quiltmaker Susana Hunter. After working the fields of her rural Alabama tenant farm and tending to her family's needs, Susana Hunter sat down to lavish her creativity on quiltmaking. On-the-fly inspiration--rather than tradition--guided her improvisational creations made from the worn clothing and fabric scraps available to her. Along with Susana Hunter’s quilts came quilting and household equipment from her simple, two-room house that had no running water, electricity, or central heat. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

Everlast "Fallen Leaves" Relish Tray, 1940 – 1941

During the early 2000s, curators sought out collections representing entrepreneurial stories to broaden our holdings. From the 1930s into the 1960s, the Everlast Metal Products Company manufactured aluminum giftware, which became fashionable during the Depression as an alternative to silver. Founded by immigrant brothers-in-law in Brooklyn, New York, they also partnered with designers, such as Russel and Mary Wright, who designed this relish tray. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

"Monarch Coffee" Thermos, circa 1931

The Henry Ford opened "Heroes of the Sky" in 2003, just in time to commemorate the centennial of the Wright brothers' first flight. Several pieces were acquired in advance of the exhibit, but this simple little vacuum flask is a favorite. It's a relatable object that helps us to imagine those early days of open cockpits and seat-of-the-pants navigation -- when a pilot had little more than coffee with which to keep warm and alert. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

4-H Uniform, circa 1948

The 4-H began as a youth program in Ohio in 1902 and by 1914 it became an official program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Federal Extension Service and cooperating state-based land-grant colleges. Boys and girls formed and managed their own local clubs. Ruth Ann Goodell joined the Eden Willing Workers 4-H Club near Garrison, Iowa, in 1942 when she was 10 years old. She sewed this uniform during the late 1940s, likely applying sewing skills she learned through club activities. The Henry Ford, anticipating the 100th anniversary of 4-H, collected this uniform as evidence of rural and farm youth culture.- Debra A. Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1990s

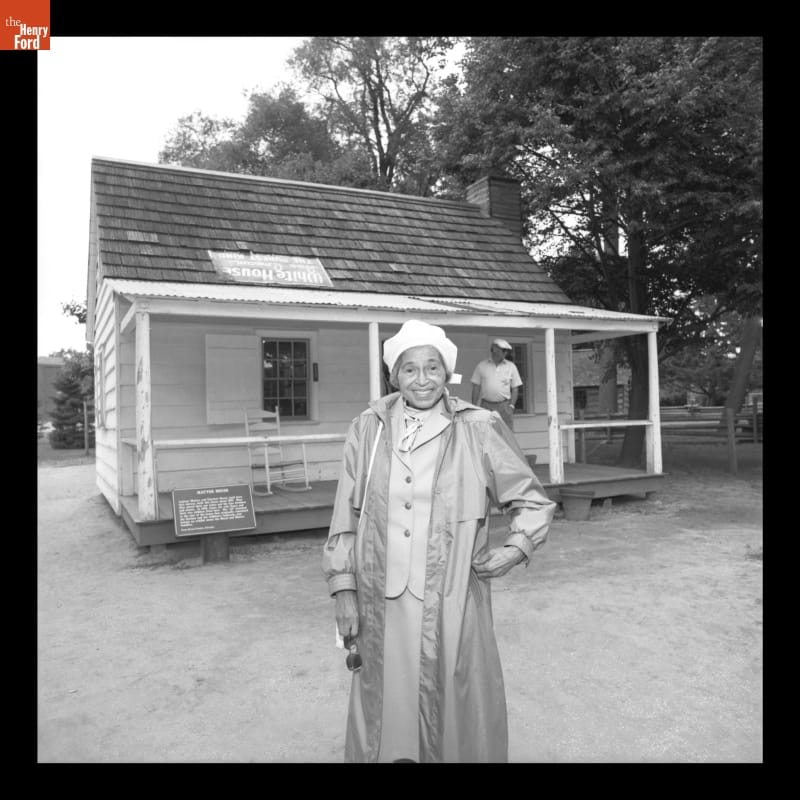

Rosa Parks Visiting Mattox House in Greenfield Village, August 1992. THF125176

By the early 1990s, museum staff decided that The Henry Ford's mission statement about America’s change through time was both too oriented toward the past and too inwardly focused on the museum’s own work.

In 1992, staff settled upon a new mission statement with three key words—innovation, resourcefulness, and ingenuity—that both aligned with Henry Ford’s original vision and provided better opportunities to impact and inspire current and future audiences. These three words shaped and energized collecting—to encompass such topics as social transformation, modern design, and the stories and objects connected with innovators and visionaries. The Museum would launch its first web site in 1995.

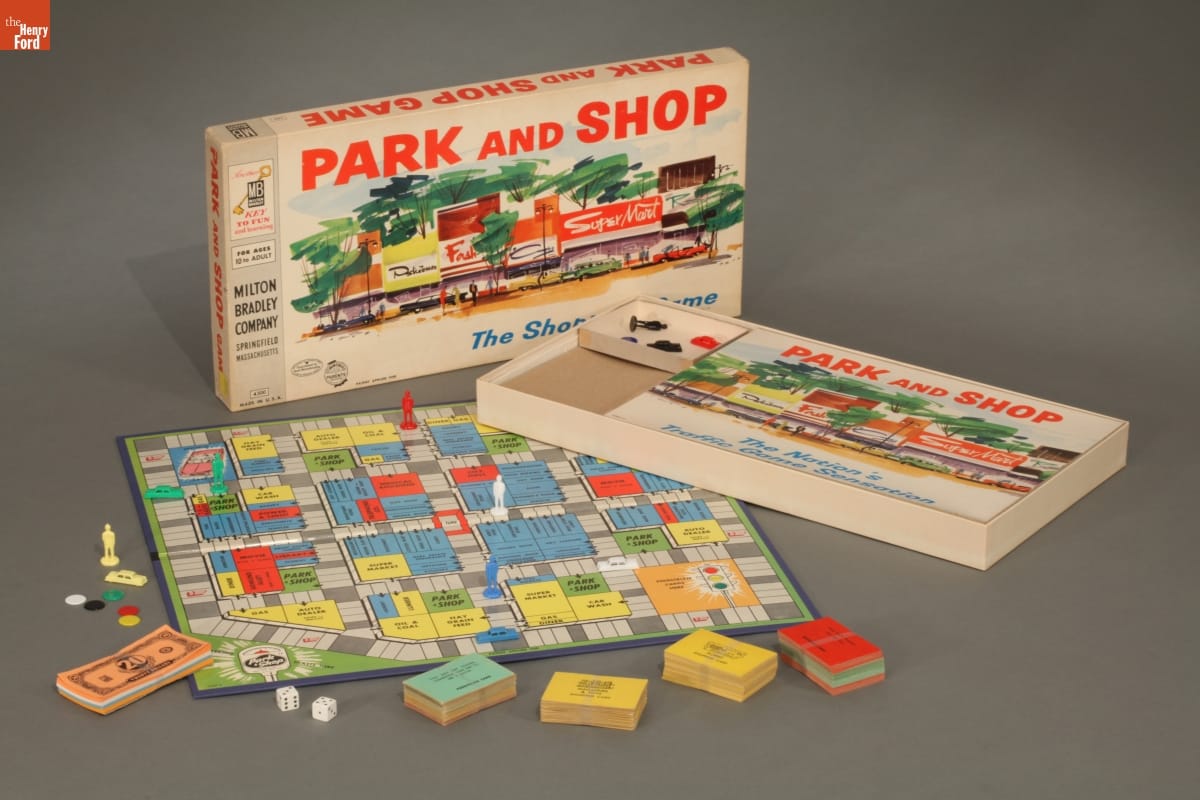

In the 1990s, collecting objects that reflected social and technological history of the second half of the 20th century increasingly became a focus. This 1960 Park and Shop game--representing a typical shopping center of the era, complete with parking lot--mirrored the rapid suburbanization of the post-World War II era as people moved from cities into the surrounding new suburbs. This game also immersed children in an adult world of shopping and consumerism. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

In the 1990s curators sought out Arts and Crafts era objects—especially those made by women—such as this charming silver and enameled jam dish and spoon, made about 1905 by silversmith Mary Winlock. Winlock was educated at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in the 1890s, and in 1903 she joined the Handicraft Shop, an artist cooperative, where she sold her distinctive enameled silver and jewelry. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

The Henry Ford's auto racing collection covers all of the most popular racing types in the United States, and it includes several landmark cars. None may be more significant than "Old 16," winner of the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup. This legendary Locomobile was the first American car to win America's first great international race, and it served notice that American-built cars were every bit as good as their European counterparts. Never restored, "Old 16" still looks much as it did at the time of that victory. We intend to preserve the car just as it is -- a rare and important survivor from motorsport's earliest years. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

During the 1990s, the museum leadership actively sought to represent more diverse American voices at Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. In response, a collections task force called for an increase in the racial, ethnic, and geographic diversity of the collections. Curators purchased images, like this one, that depicted the lives of African Americans, Jews, and immigrant populations. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

The Henry Ford's collection of mid-20th century design expanded as the century came to a close. In 1992, the Herman Miller furniture company donated a substantial collection of material designed by Alexander Girard, the Director of Design of Herman Miller's textile division from 1952-1973. Girard's incredible eye for color, texture, and whimsy helped transform the aesthetic of the modern movement. - Katherine White, Associate Curator

In the 1990s, the museum assessed its holdings and developed guidelines for future collecting. The acquisition of a group of pictorial lunchboxes in 1999 reflected a new focus on post-World War II America. Introduced in 1950, pictorial lunchboxes relate to mass media, merchandising, and the Baby Boomer generation. Curators selected lunchboxes representing current events and popular culture, especially TV shows and movies. -Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Large machine designed to harvest a delicate crop - the mass-produced and processed tomato. Tomato genetic research in California made the machine viable but this machine was sold in Ohio to a northern Illinois truck farming family. The story is essential to conveying the massive scale required to put canned tomatoes on grocery store shelves. - Debra Reid, Curator of Agriculture and the Environment

#Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum, THF90

Celebrating Ninety: Collecting in the 1980s

Construction at Firestone Farm in Greenfield Village, January 1985. THF138461

Guided by the 1980s mission-based phrase, “Stories of a Changing America,” Greenfield Village took on new life and Henry Ford Museum exhibits explored new topics. These included the acquisition of the Firestone farmhouse and creation of its living history program (1985), the “Automobile in American Life” exhibit (1987), and the “Made in America” exhibit (1992). During the 1980s and 1990s, museum staff placed new attention on accurate research, creative program planning, and engaging public presentations.

Additions the collections: 1980s

Elizabeth Parke Firestone donated a large segment of her stunning wardrobe in 1989, including custom-made garments created for her by prominent American and European couturiers. Firestone was an early client of French designer Christian Dior, who had just caused a sensation introducing his “New Look” to a post-WWII world, emphasizing slim waists and rounded feminine features. Firestone visited Dior’s Paris salon in 1946 and commissioned this dress, made for her daughter Martha’s wedding to William Clay Ford. - Jeanine Head Miller, Curator of Domestic Life

This type of lamp is typically called a "Television Lamp." It was made to sit atop a television console and to provide a low level of illumination, sufficient to keep one's eyes from being "harmed" by watching the small TV screens of that time (1946-1960). This marks a change in collecting as curators sought out objects that provided insight into social history. - Charles Sable, Curator of Decorative Arts

For 50 years Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation generally presented artifacts in a traditional typological format. Tractors, airplanes, furnishings -- you name it -- sat in tidy rows where visitors were left to trace an item's technological evolution. That all began to change in the 1980s as the museum refocused on social history. No exhibit signaled this shift more dramatically than "The Automobile in American Life," opened in 1987. Cars were moved out of their stodgy rows and instead placed alongside contextual items like maps and travel literature, menus from quick-service restaurants, and replicated roadside lodgings. This Holiday Inn "Great Sign" was one of the more visible artifacts acquired for the new show. - Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

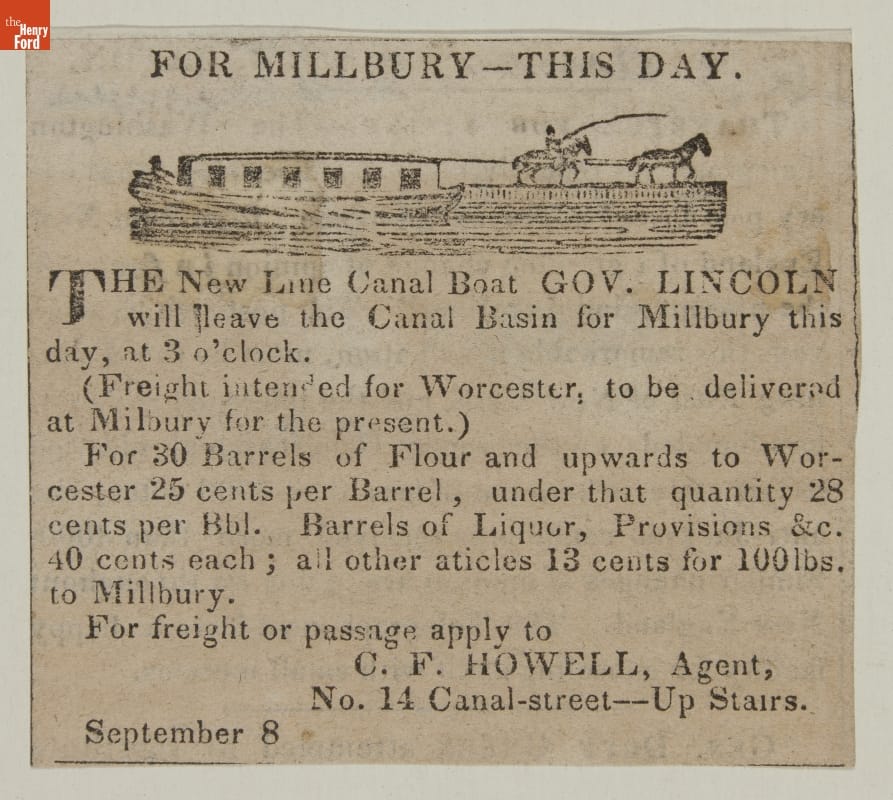

In 1982, Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village purchased the Seymour Dunbar Collection from Chicago's Museum of Science & Industry. The collection consists of over 1,700 prints, drawings, maps, and other items documenting various modes of travel from 1680 to 1910. Dunbar compiled this material while researching his four-volume history of travel in the U.S., which was published in 1915. - Andy Stupperich, Associate Curator, Digital Content

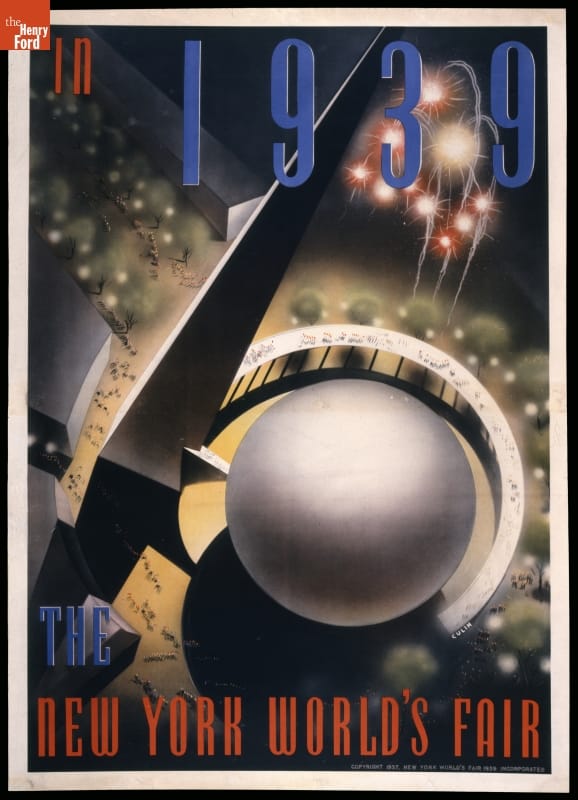

Reflecting a new emphasis on social history, museum staff developed interpretive exhibits that integrated objects from across collections categories to examine special themes. “Streamlining America” explored an influential mid-20th-century ideology and design style. This striking poster, selected for the exhibit, embodies the streamlined environment of the 1939-40 New York World’s Fair. - Saige Jedele, Associate Curator, Digital Content

Harold K. Skramstad, Jr., president of The Edison Institute, considered the opening of Firestone Farm a "landmark event." Why? The house, barn, and outbuildings added a living historical farm to Greenfield Village, complete with wrinkly Merino sheep collected to sustain the type and increase interpretive potential. - Debra A. Reid, Curator, Agriculture and the Environment

Henry Ford Museum, Greenfield Village, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford, THF90