Posts Tagged by debra a. reid

Healthy Food to Build Healthy Communities

What measures do you use to judge whether food is “healthy”? What connections do you see between healthy food and healthy communities? Today the concept of “food security” links nutritious food to individual and community health. This blog features historical resources in the collections of The Henry Ford that help us explore the meaning of “food security.” Many relate to the work of Black agricultural scientist George Washington Carver with Black farm families in and around Tuskegee, Alabama, between the 1890s and 1940s.

What Does "Food Security" Mean to You?

A big meal often symbolizes food security. You can almost smell the roast goose (once preferred to turkey) and taste the fresh apples, oranges and bananas in this centerpiece on a family’s holiday table!

Family Seated at Dining Table for a Holiday Meal, circa 1945. THF98738

But does having a big meal on special occasions mean that a person, a family, or a community is “food secure”?

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) explains that a person is “food secure” if they have regular access to safe and nutritious food in amounts required for normal growth and development and in quantity and calories needed to maintain an active and healthy life.

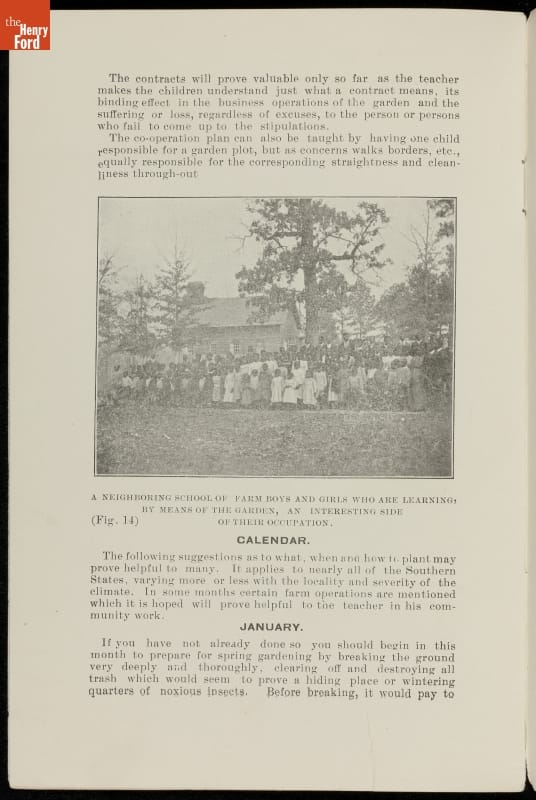

Students at this South Carolina school all appear healthy. This implies that they have access to a quantity of nutritious food necessary for normal growth. It also implies that they consume it consistently which helped keep them healthy and better able to complete their schoolwork.

School Teacher and Her Students, Pinehurst Tea Plantation, Summerville, South Carolina, circa 1903. THF115900

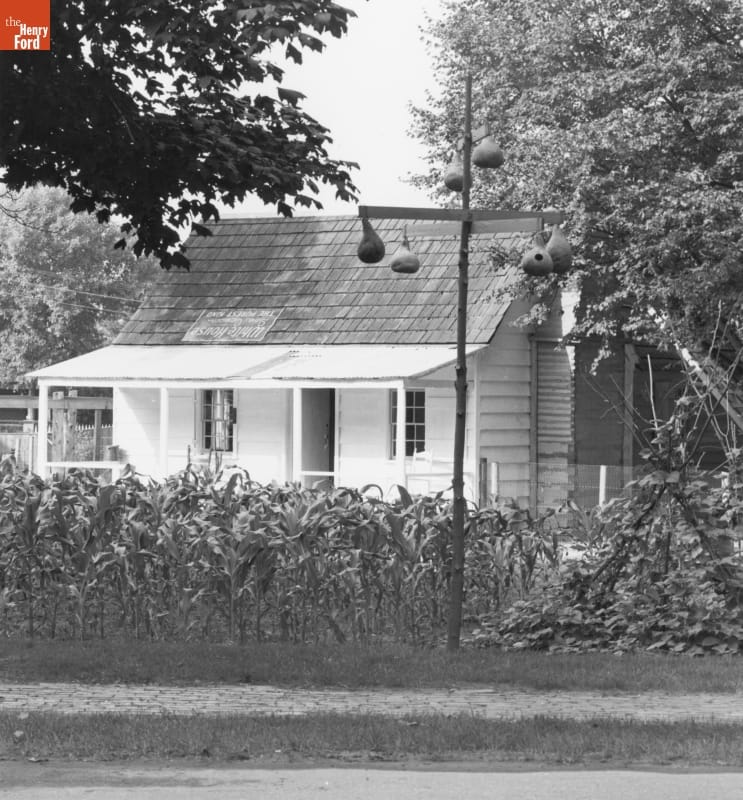

Historically, many farm families raised much of the food they needed to survive, including meat, vegetables, grains, and fruit. The Mattox family farmed their own land, and they dedicated time and energy to tending their garden and raising their own beans and sweet corn (as pictured in this photograph). Being responsible for your own food supply required careful planning and hard work year-round because families had to grow, process, preserve, and then prepare and consume what they (and their livestock) ate. As long as everything went according to plan, and no disasters arose, a family might be food secure.

Mattox Family Home in Greenfield Village, 1991. THF45319

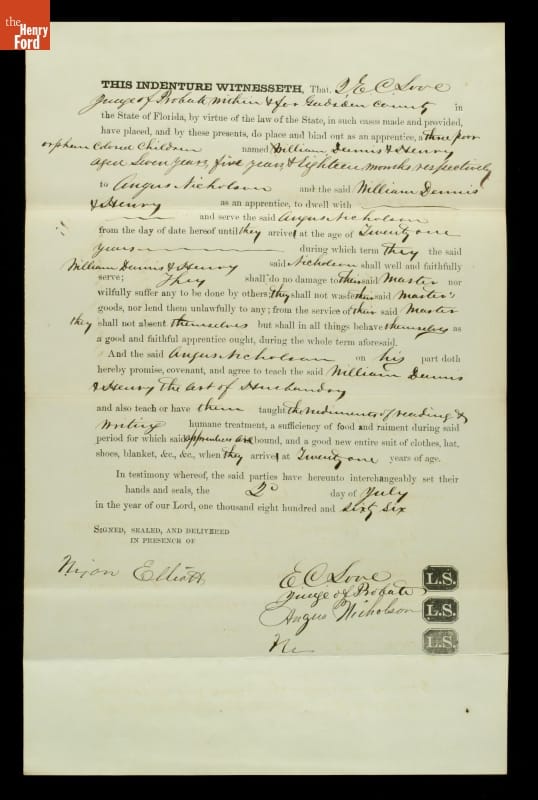

Many factors led to food insecurity. This indenture for three orphaned children, William (7 yrs old), Dennis (5 yrs old) and Henry (18 months old), specified that they receive “a sufficiency of food.” What did “sufficiency” mean? Consuming calories might provide energy to work, but calories alone did not (and do not) ensure a healthy life. Furthermore, being unfree made these indentured children dependent on someone else who might have other ideas about what “sufficiency of food” meant.

Indenture for "...Colored Children Named William, Dennis & Henry," July 20, 1866. THF8563

Cotton and Food Insecurity

Southern farm families often grew cotton as their cash crop. Farm families could not eat cotton though the seed yielded byproducts used in livestock feed, and oil that became a popular cooking ingredient. Landowners and tenant farmers could strategize how much cotton to grow, and could plant corn to feed their hogs, and could dedicate land for a garden. Yet, many families across the rural South, Black and white alike, farmed cotton, and they received a share of the crop they grew as payment for a year of labor. Owners expected these sharecroppers to focus their energy on the cash crop – cotton - and not spend valuable labor on raising their own food. Instead, families became even more economically insecure by buying inexpensive food on credit.

Picking Cotton, Louisiana, 1883-1900. THF278896

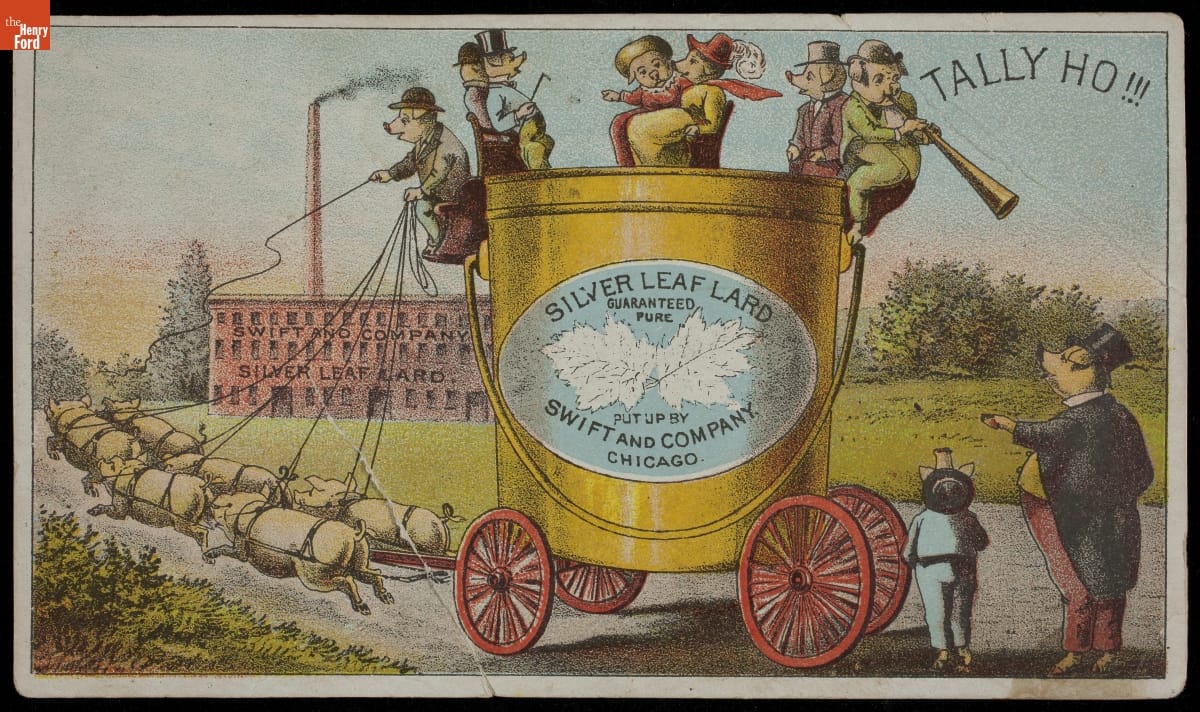

Many sharecroppers and agricultural laborers in the South lived on a diet of meat (pork), meal (cornmeal) and molasses (processed from either sugar cane or sorghum) – the 3M diet. While pork in its many forms (including lard sandwiches) and cornbread with molasses provided much needed calories, the 3M diet did not deliver nutrients needed to maintain health. Niacin deficiencies led to the debilitating disease, pellagra, which afflicted impoverished people across the South and beyond.

Trade Card for Silver Leaf Lard, Swift & Company, 1870-1900. THF225588

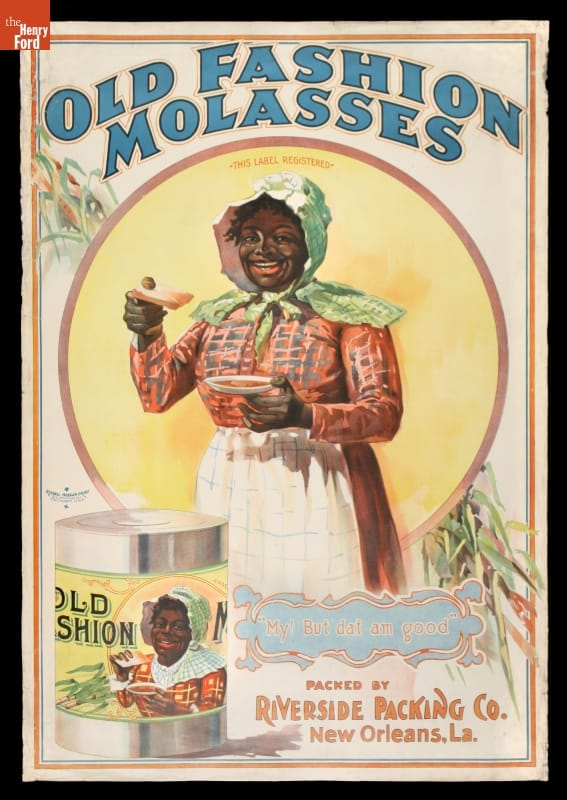

Inadequate supplies of food, and diets lacking in nutrients, undermined food security. Racism also undermined access to adequate foods. Graphic arts advertising southern staples often reinforced racist stereotypes rather than reality – that Black women often held positions of authority as Black cooks who prepared meals for others who could afford fresh foods and a varied and nutritious diet.

Advertising Poster, "Old Fashion Molasses," circa 1900. THF8044

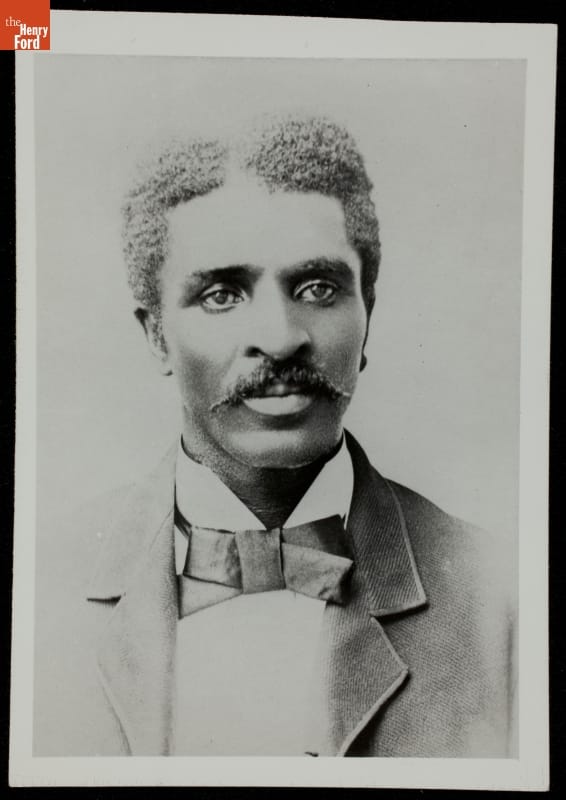

Improving rural health required a revolution that reduced the dependency on cotton and increased the types of crops grown for market. George Washington Carver, the first Black American to hold an advanced degree in agricultural science, used his knowledge to try to convince farmers to improve soils to increase cotton yields, but to also raise additional crops such as sweet potatoes and peanuts.

George Washington Carver's Graduation Photo from Iowa State University, 1893. THF214111

George Washington Carver’s Work with Peanuts

Many associate Carver with peanut butter, but his relationship to peanuts far exceeds peanut butter.

A man in Montreal, Canada, secured a U.S. Patent for peanut candy – a paste sweetened with sugar – in 1884. At that time George W. Carver had been living for five years in Kansas working as a cook and laborer. Between 1886 and 1888, after being refused entry into a college in Kansas, Carver homesteaded near Beeler, Kansas.

Alabama, the location of Tuskegee Institute, where Carver went to work in 1896, ranked fourth in peanut production in 1900 behind Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. Farmers in these states raised most of the raw product that Northern food processors like H.J. Heinz dry roasted and ground into peanut butter. This Heinz peanut-butter packaging features a blond blue-eyed girl in a grain field holding lilacs. This did not accurately represent southern farm families raising the high-quality crop that Heinz depended on for its “choicest peanuts.”

Trade Card for H.J. Heinz Company, “Mama’s Favorites,” circa 1905. THF215296

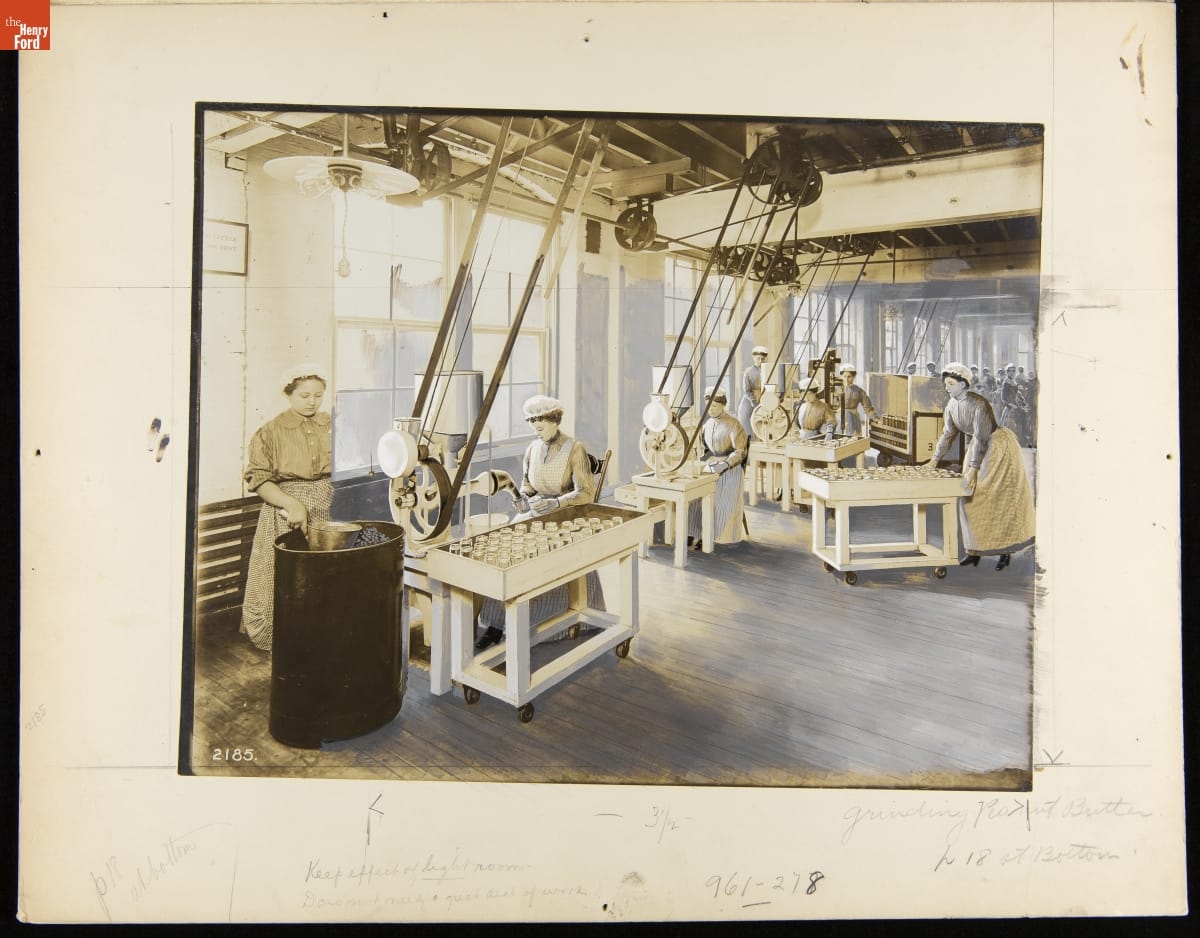

As consumer demand for peanut butter increased, production increased. Nutritionists understood the value of peanuts and of peanut butter as an inexpensive source of plant-based protein, fats, minerals and vitamins. Farm families could eat their own home-grown peanuts but could also find a ready market for them.

Women grinding peanuts into peanut butter at Heinz. THF292973

Tuskegee, Alabama was located just north of the peanut-growing region of southeastern Alabama. Carver set about to convince Black landowning farmers in and around Tuskegee to take advantage of the market opportunity. Orchestrating a more complete overhaul of cotton-dependent Alabama agriculture required convincing white landowners to free sharecroppers from requirements to grow only cotton. Others sought a revolution in civil rights through legal means. Even though many criticized the self-help message, families who ate better could channel new-found energy toward securing civil rights and social justice.

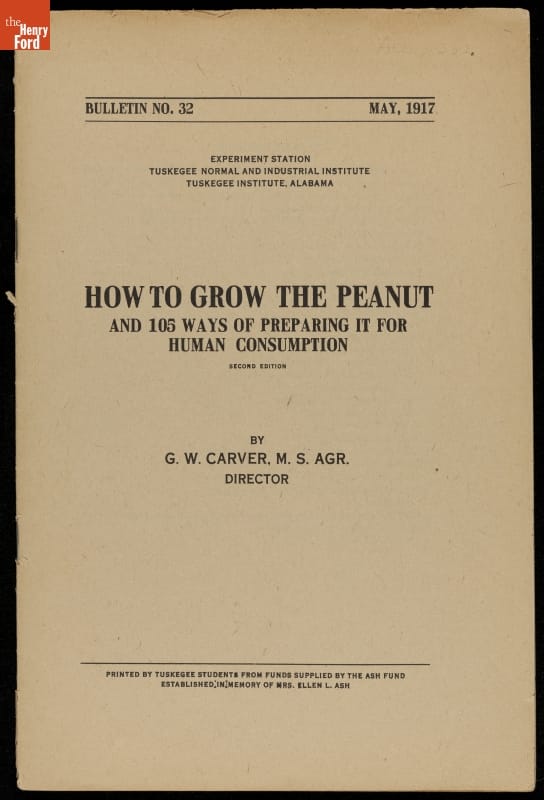

Carver appealed to his constituents in writing. He linked concerns about health and nutrition to economic independence in his May 1917 pamphlet, “How to Grow the Peanut.”

Bulletin, How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption, 1917. THF213329

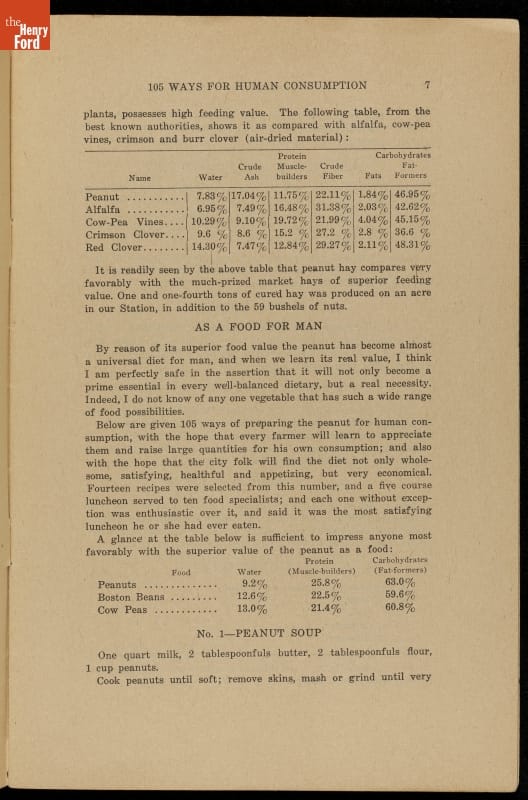

Carver described the peanut as having “limitless possibilities.” The “nuts possess a wider range of food values than other legumes.” THF213331

Carver described 105 ways to prepare the peanut – ground, boiled, roasted, and as a main ingredient in soups, salads, candy, and replacement for chicken, and other meats. THF213335

Crop Innovations

Carver applied his life-long fascination with plants to identify crops in addition to the peanut that had the potential to displace cotton. He used this weeder to collect specimens. He studied their molecular composition, extracted byproducts, and devised new uses for them.

Weeder Used by George Washington Carver at Greenfield Village, 1942; Gift of Henry and Clara Ford. THF152234.

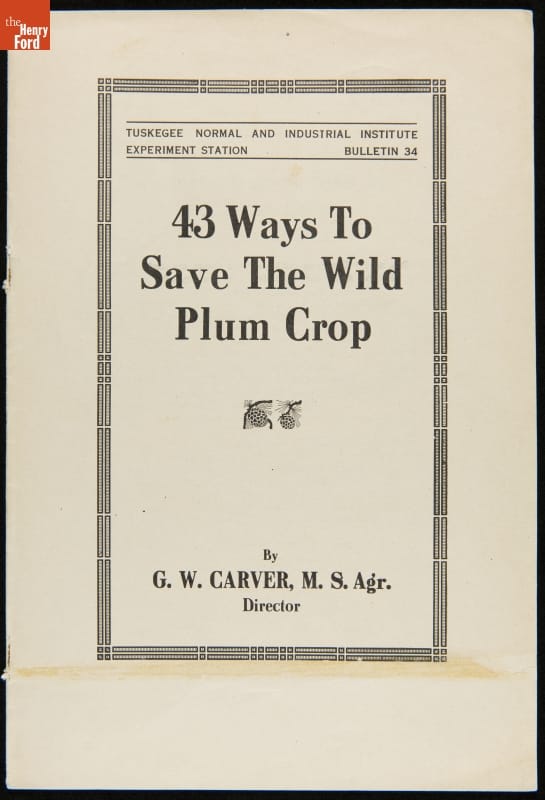

Carver promoted crops through short publications that stressed financial and food security.

Some crops occurred naturally, the wild plum, for instance, which landowning farmers might have on their property but that they undervalued as a food source.

Bulletin, “43 Ways to Save the Wild Plum Crop,” 1917. THF288049

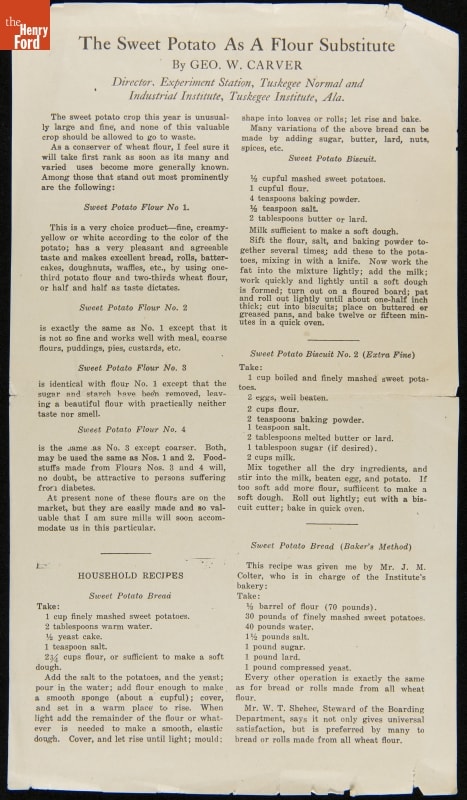

During World War I, Carver promoted crops that Alabama farmers grew, but that could be processed into alternatives to wheat flour. THF290275

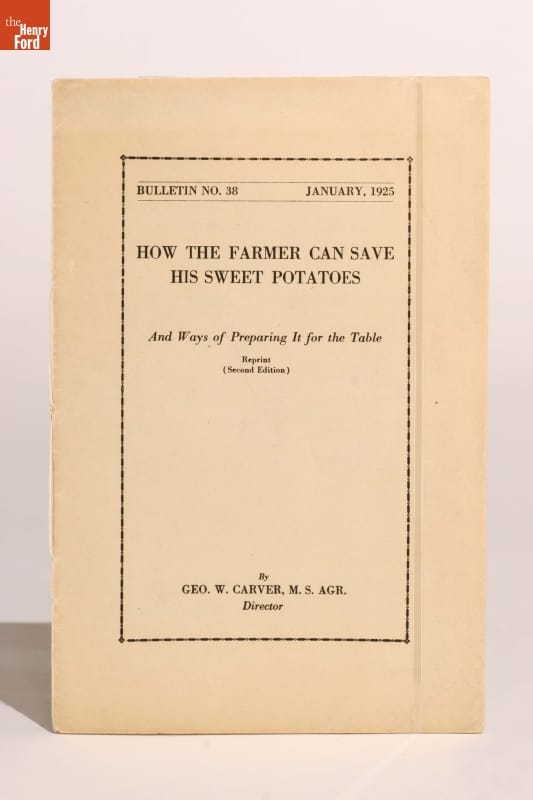

During the 1920s, Carver urged farmers to grow even more crops that they could eat, such as sweet potatoes.

How the Farmer Can Save His Sweet Potatoes, 1925. THF37735

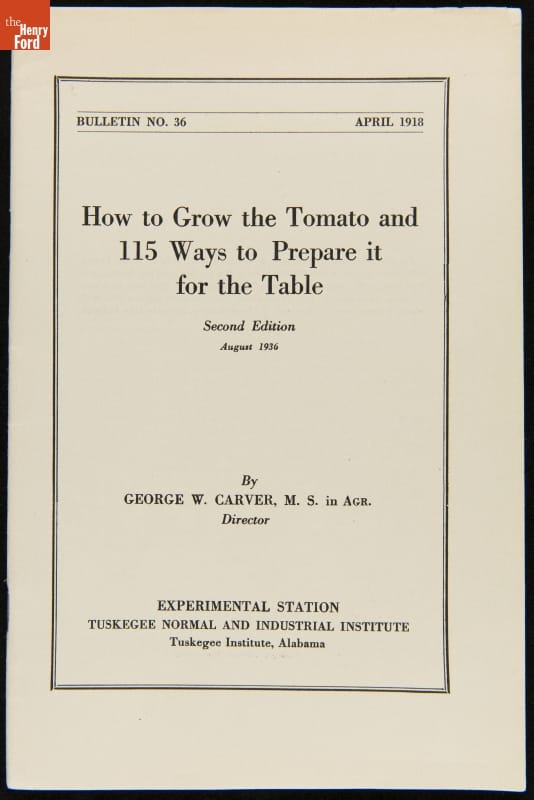

During the 1930s, as economic conditions worsened during the Great Depression, Carver published a pamphlet focused on growing the tomato, a vitamin- and mineral-rich food source.

Bulletin, “How to Grow the Tomato and 115 Ways to Prepare it for the Table,” 1936. THF288043

Carver, Food Byproducts, and Food Security

Carver’s research into plant byproducts and new foods from farm crops caught the attention of Henry Ford.

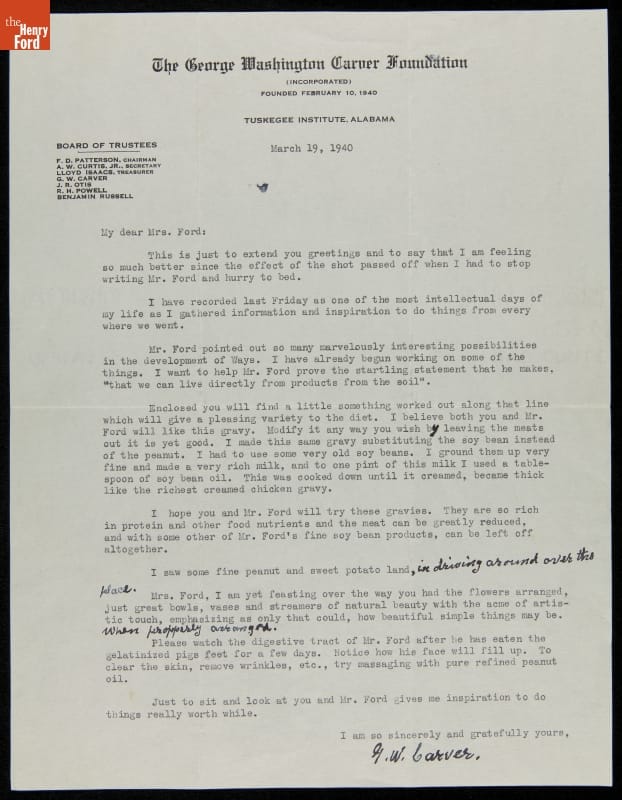

Carver and Clara and Henry Ford corresponded about topics as practical as gravy made from soy and peanut flour, and as personal as digestive systems.

Letter from George Washington Carver to Clara Ford, March 19, 1940. THF213553

Henry Ford recognized Carver’s inspiration by naming the Nutrition Laboratory in his honor on 21 July 1942.

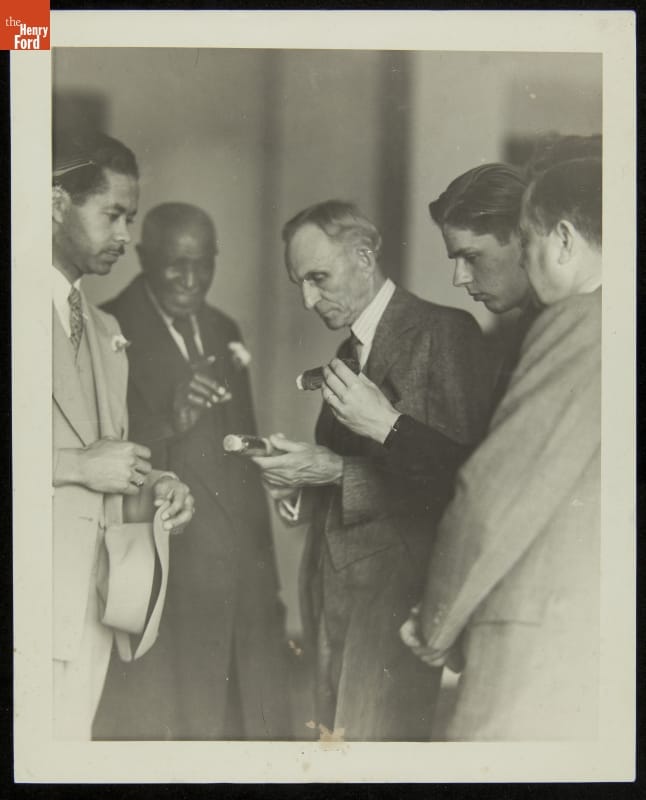

George Washington Carver and Edsel Ford at the Carver Nutrition Laboratory, Dearborn, Michigan, 1942. THF213823

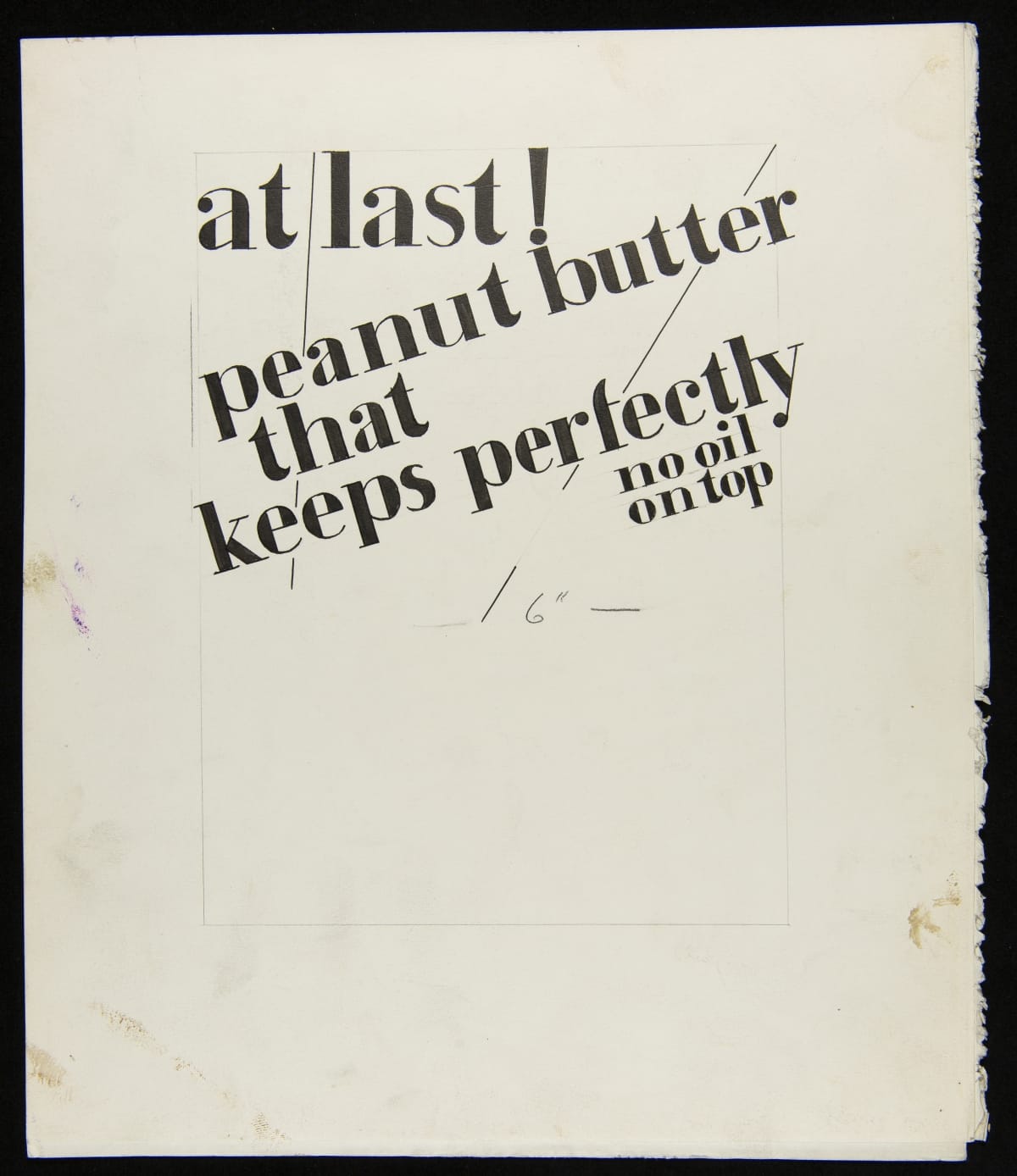

Peanut Oil: A Byproducts Many Uses

Carver explained that peanut oil (separated from peanut paste) was “one of the best-known vegetable oils.” You can see oil, sitting atop the peanut paste, if you look for “natural peanut butter” at your local grocery store. Food chemists experimented with how to prevent the oil from separating from the ground peanut paste. Preventing separation requires hydrogenation, which changes the chemical composition of unsaturated fats and turns them into saturated fats. Heinz drafted advertisements to promote the new hydrogenated peanut butter to consumers as this example indicates.

At Last! No oil on top. THF292249

The varied uses of peanut oil that Carver promoted increased market opportunities for impoverished farmers which increased their food security. To that end, Carver experimented with peanut oil as a rub to relieve the discomfort that polio patients suffered. While science could not link the peanut oil itself to positive benefits, the process of messaging the oil into the patient reduced pain by manipulating the muscles.

Photographic print, Austin Curtis, George Washington Carver, Henry Ford, Wilbur Donaldson and Frank Campsall Inspect Bottles of Peanut Oil, Tuskegee Institute, March 1938. THF213794

Healthy Communities

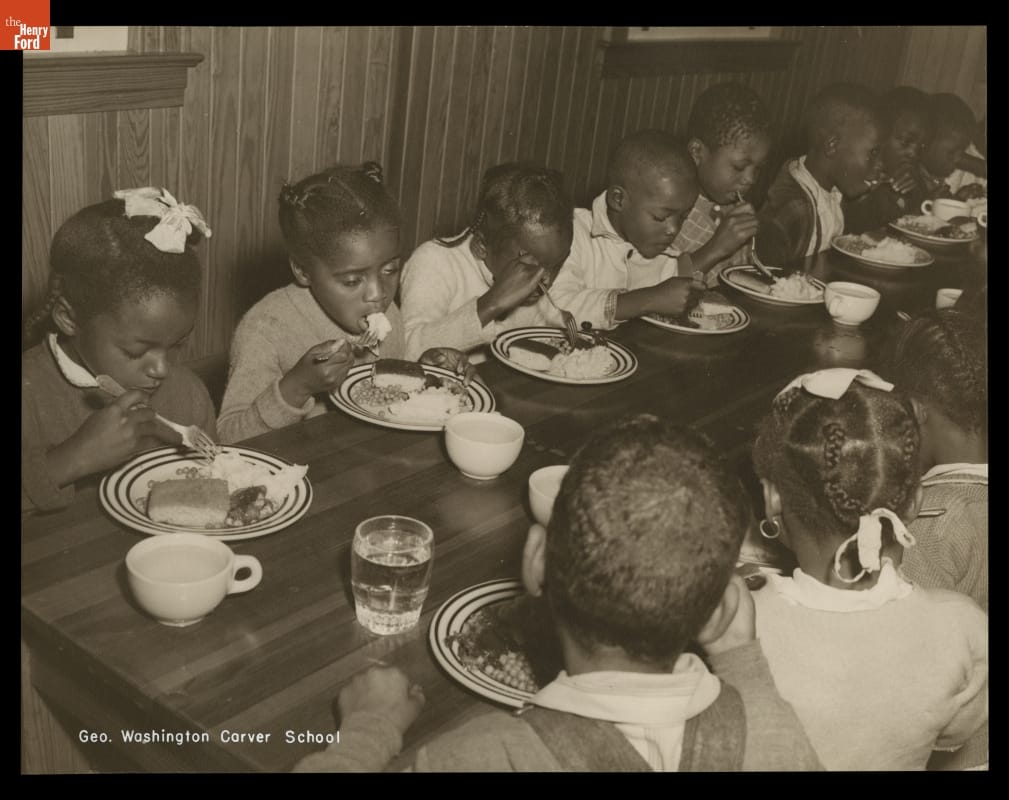

Building healthy communities started with individuals but grew through collective effort. Farm families, schools, businesses, church groups, and investors each committed resources to the cause. National intervention furthered local goals. The 1946 National School Lunch Act increased access to good food for all school children, not just those who could help themselves.

Photographic Print, Cafeteria at George Washington Carver School, Richmond Hill, Georgia, circa 1947. THF135671

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food insecurity, George Washington Carver, food, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, African American history, #THFCuratorChat

How Does Your Vegetable Garden Grow?

Do you raise vegetables to feed yourself? If the answer is “Yes,” you are not alone. The National Gardening Survey reported that 77 percent of American households gardened in 2018, and the number of young gardeners (ages 18 to 34) increased exponentially from previous years. Why? Concern about food sources, an interest in healthy eating, and a DIY approach to problem solving motivate most to take up the trowel.

The process of raising vegetables to feed yourself carries with it a sense of urgency that many of us with kitchen cabinets full of canned goods cannot fathom. Farm families planted, cultivated, harvested, processed and consumed their own garden produce into the 20th century. This was hard but required work to satisfy their needs.

Two members of the Lancaster Unit of the Woman’s National Farm and Garden Association digging potatoes, 1918. THF 288960

Seed Sources

Gardeners need seeds. Before the mid-19th century, home gardeners saved their own seeds for the next year’s crop. If a disaster destroyed the next year’s seeds, home gardeners had to purchase seeds.

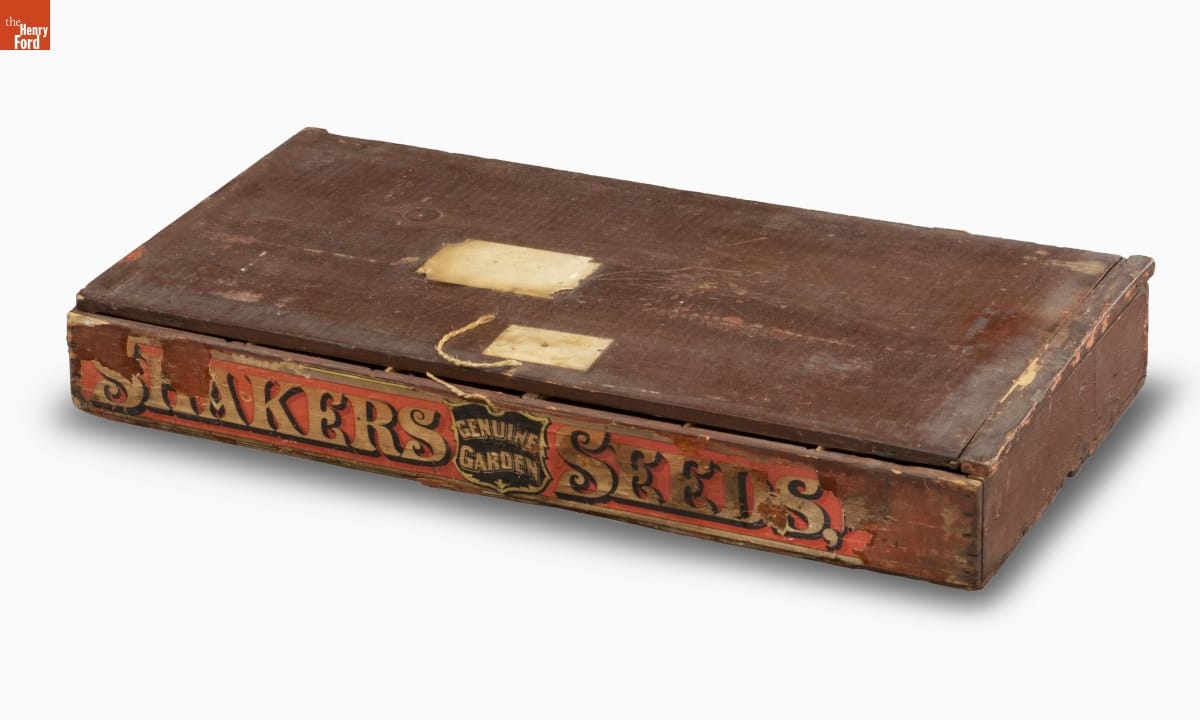

Commercial seed sales began as early as 1790 in the community of Shakers at Watervliet, New York. The Mt. Lebanon, New York, Shaker community established the Shaker Seed Company in 1794. The Watervliet Shakers first sold pre-packaged seeds in 1835, but the Mt. Lebanon community dominated the garden seed business until 1891. They marketed prepackaged seeds in boxes like this directly to store owners who sold to customers.

Shakers Genuine Garden Seeds Box, 1861-1895. THF 173513

Satisfying the demand for garden seeds became big business. Entrepreneurs established seed farms and warehouses in cities where laborers cultivated, cleaned, stored and packaged seeds. The D.M. Ferry & Co. provides a good example.

D.M. Ferry & Company Headquarters and Warehouse, Detroit, Michigan, circa 1880. THF76854

Entrepreneurs invested earnings into this lucrative industry.

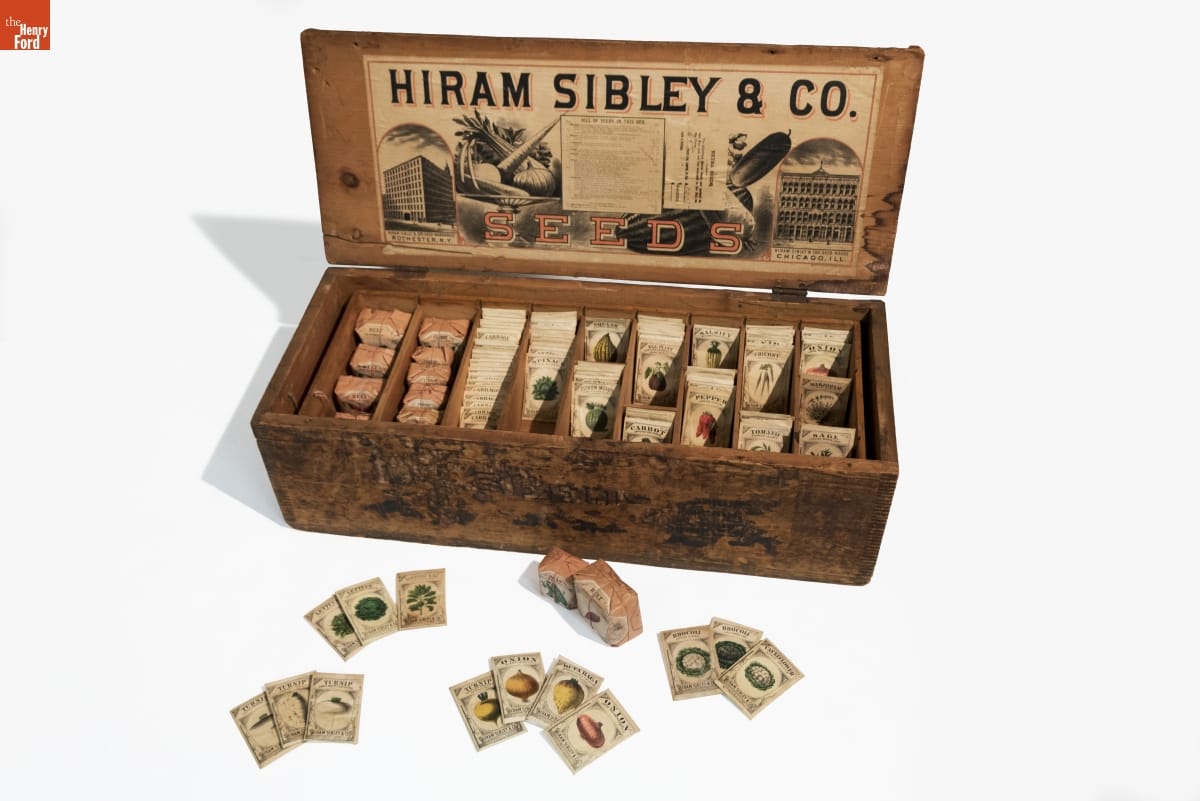

Hiram Sibley, who made a fortune in telegraphy, and spent 16 years as president of the Western Union Telegraph Company, claimed to have the largest seed farm in the world, and an international production and distribution system based in Rochester, New York, and Chicago, Illinois. Though the company name changed, the techniques of prepackaging seeds developed by the Shakers at Watervliet and direct marketing of filled boxes to store owners remained an industry standard.

Hiram Sibley & Co. Seed Box, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181542

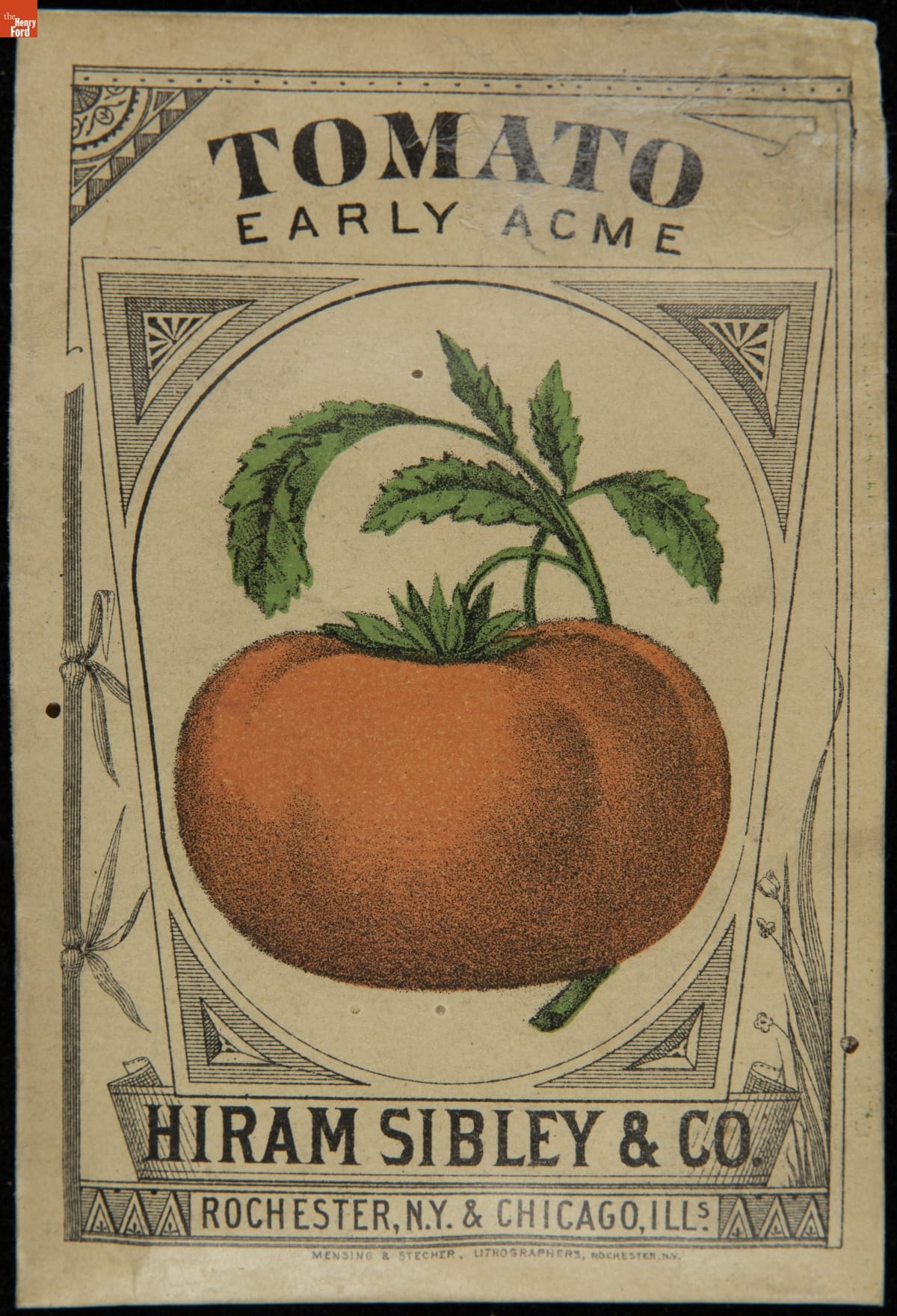

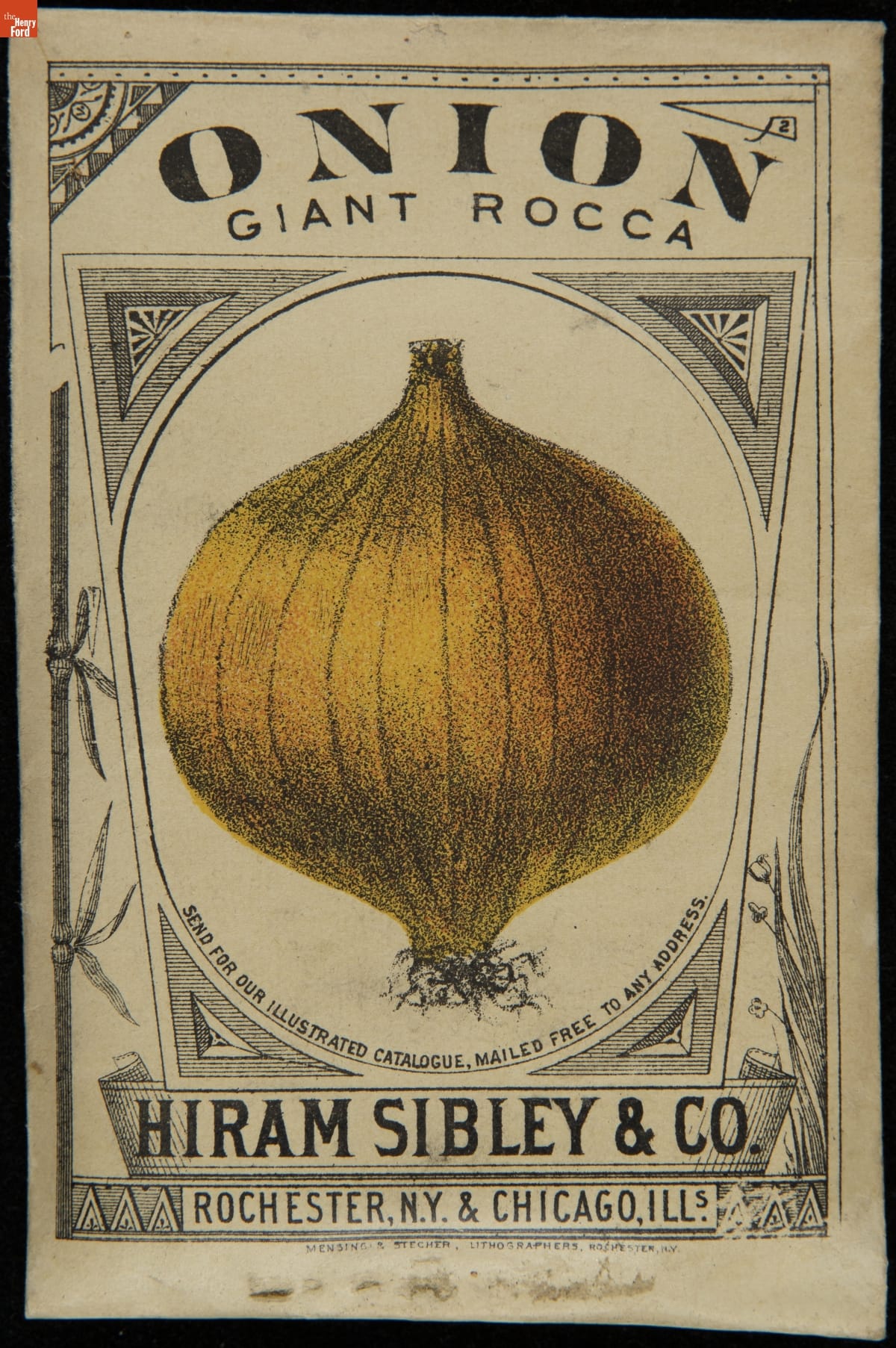

Planting gardens requires prepackaged seeds (unless you save your own!). These little packets tell big stories about ingenuity and resourcefulness. We acquired this 1880s Sibley & Co. seed box from the Barnes Store in Rock Stream, NY in 1929.

The original Sibley seed papers and packets are on view in a replica Hiram Sibley & Co seed box in the J.R. Jones General Store in Greenfield Village, which our members and guests will be able to enjoy once again when we reopen. Until then, take a virtual trip to the store by way of Mo Rocca and Innovation Nation.

Looking for gardening inspiration? Historic seed and flower packets can provide plenty! Survey the hundreds of seed packets dated 1880s to the present in our digital collections and create your own virtual garden.

The variety might astound you, from the mangelwurzel (raised for livestock feed) to the Early Acme Tomato and the Giant Rocca Onion.

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Beet Long Red Mangelwurtzel” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF181520

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Tomato Early Acme” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF278980

Hiram Sibley & Co. “Onion Giant Rocca” Seed Packet, Used in the C.W. Barnes Store, 1882-1888. THF279020

Families in cities often did not have land to cultivate, so they relied on the public markets and green grocers as the source of their vegetables.

Canned goods changed the relationships between gardeners and their responsibility for meeting their own food needs. Affordable and available canned goods made it easy for most to hang up their garden trowels. As a result, raising vegetables became a lifestyle choice rather than a necessity for most Americans by the 1930s.

Can Label, “Butterfly Brand Stringless Beans,” circa 1880. THF293949

Times of crisis increase both personal interest and public investment in home-grown vegetables, as the national Victory Garden movements of the 20th century confirm.

Victory Gardens

Man Inspecting Tomato Plant in Victory Garden, June 1944. THF273191

Victory Gardens, a patriotic act during World War I and World War II, provide important examples of food resourcefulness and ingenuity.

You can find your own inspiration from Victory Garden items in our collections – from 1918 posters to Ford Motor Company gardens during the 1930s, and home-front mobilization during World War II here.

Woman's National Farm and Garden Association at Dedham Square Truck Market, 1918. THF288964

But the “fruits” of the garden didn’t just stay at home. Entrepreneurial-minded Americans took their goods to market, like these members of the Woman's National Farm & Garden Association and their "pop-up" curbside market in Dedham, Massachusetts, in 1918.

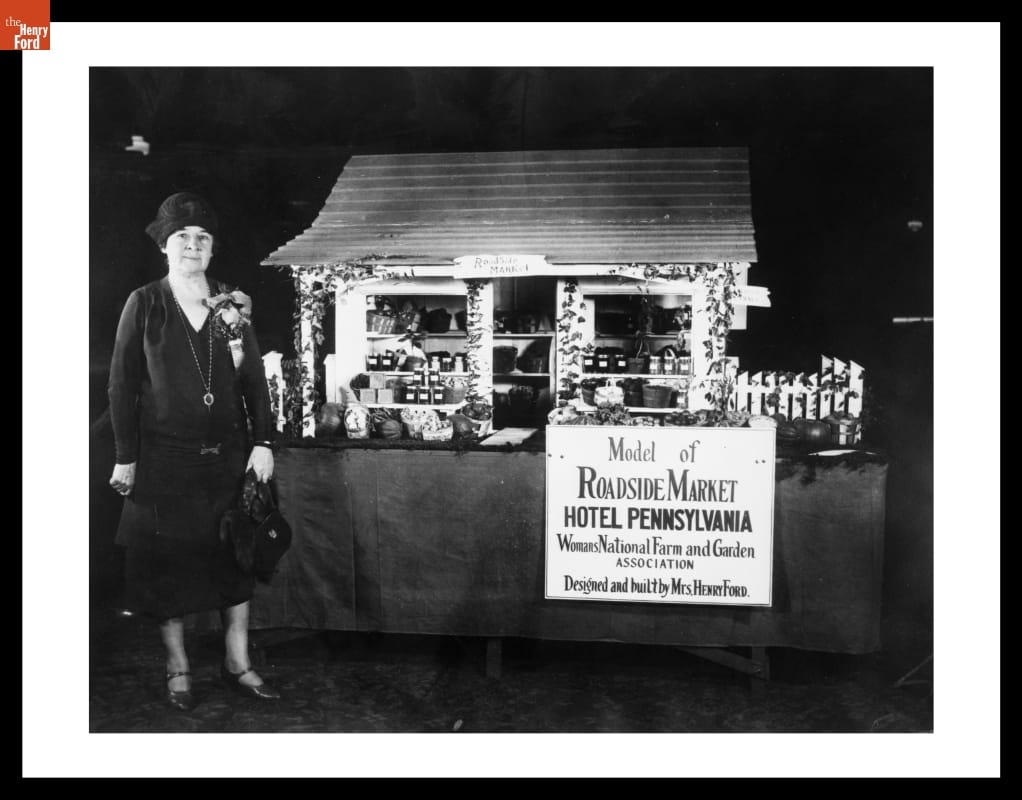

Clara Ford with a Model of the Roadside Market She Designed, circa 1930. THF117982

Clara Ford, at one time a president of the Women’s National Farm and Garden Association, also believed in the importance of eating local. Read more about her involvement with roadside markets here.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

food, agriculture, gardening, #THFCuratorChat, by Debra A. Reid

Celebrating Earth Day

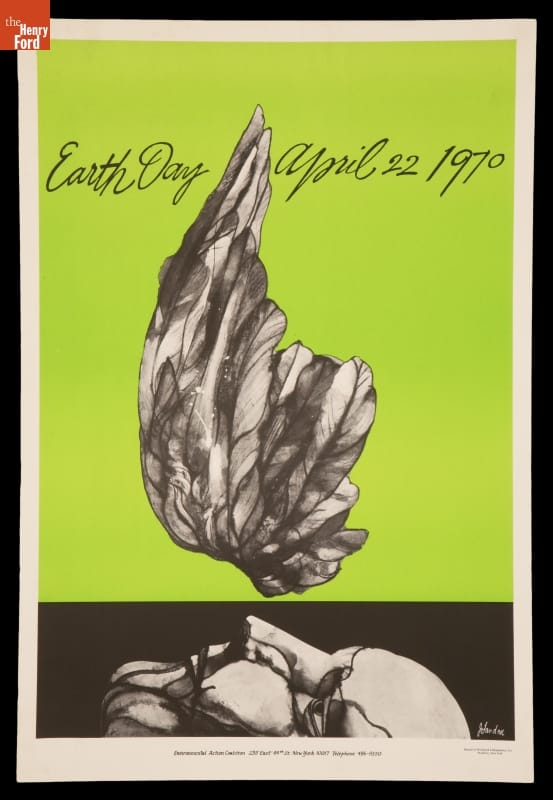

As we celebrate Earth Day, do you know which iconic symbol for the environmentalism movement came first? The bird wing design on an Earth Day poster or the “Give Earth a Chance” button? If you thought it was the button, you’re correct.

Give Earth a Chance Button, 1970. THF284833

Students at the University of Michigan formed ENACT (Environmental Action for Survival Committee, Inc.) in 1969. They prototyped the button and started selling it in late 1969, months before the official Earth Day on April 22, 1970. This button was reputedly worn during Earth Day 1970.

Advertising Poster, "Earth Day April 22, 1970.” THF81862

If you picked the wing, the artist that created the poster, Jacob Landau, used a stylized wing in earlier artwork. Landau, an award-winning illustrator and artist, taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He created this poster for the Environmental Action Coalition which coordinated New York Earth Day activities in 1970.

Did Earth Day launch the Age of Conservation?

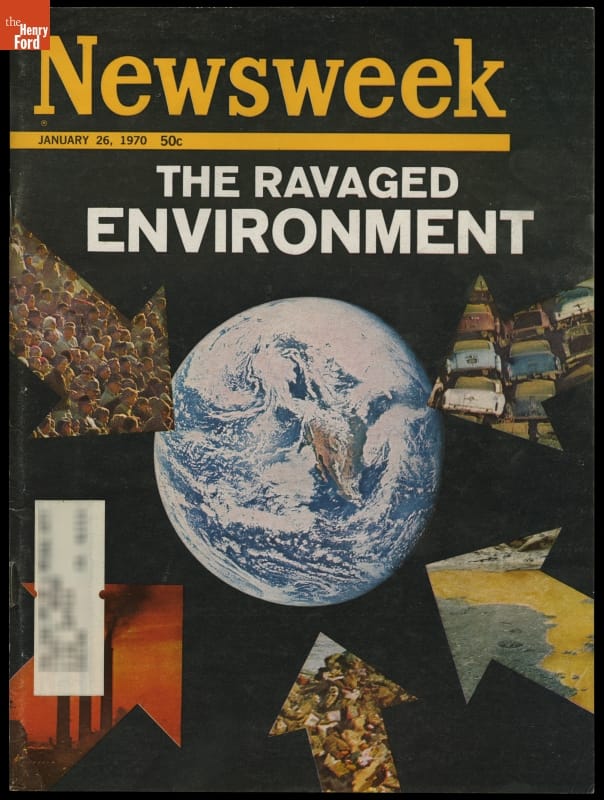

“Newsweek” Magazine. THF139548_redacted

Newsweek itemized threats that ravaged the environment in its January 26, 1970 issue. All resulted from human actions. Emissions and sewage polluted the air and water. Garbage clogged landfills. Population growth threatened to overtake available food supplies. Solving these challenges required cooperation and unity on the part of individuals as well as local, state, and national governments. Editors believed that replenishing the environment to sustain future generations could be “the greatest test” humans faced. They featured the “Give Earth a Chance” button with the caption: "Symbol of The Age of Conservation?"

What to do to save the Earth?

The overall goal of replenishing the environment to sustain future generations required action on many fronts. More than 20 million people across the United States participated in the first Earth Day. The teach-ins informed, marches conveyed the intensity of public interest, and graphic arts spoke volumes about what needed to be done.

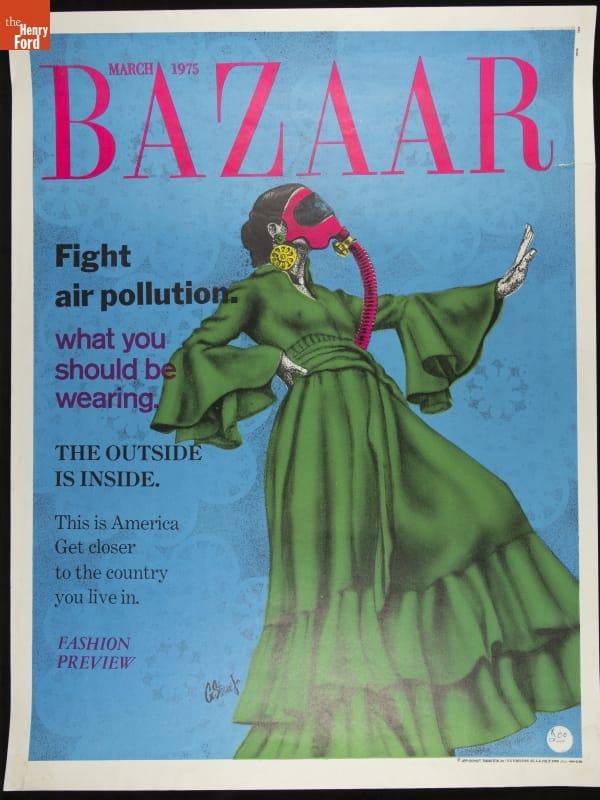

“March 1975, Bazaar, Fight Air Pollution, What You Should Be Wearing,” Poster, 1970. THF288328

This 1970 poster envisioned high fashion of the future, complete with a gas mask accessory. The moral of the story? Self-protection would not solve the problem of environmental pollution.

The Clean Air Act of 1970 empowered states and the national government to reduce emissions through regulation. This applied to industrial emissions as well as mobile sources (trains, planes, and automobiles, among others).

Interest in Recycling Grows

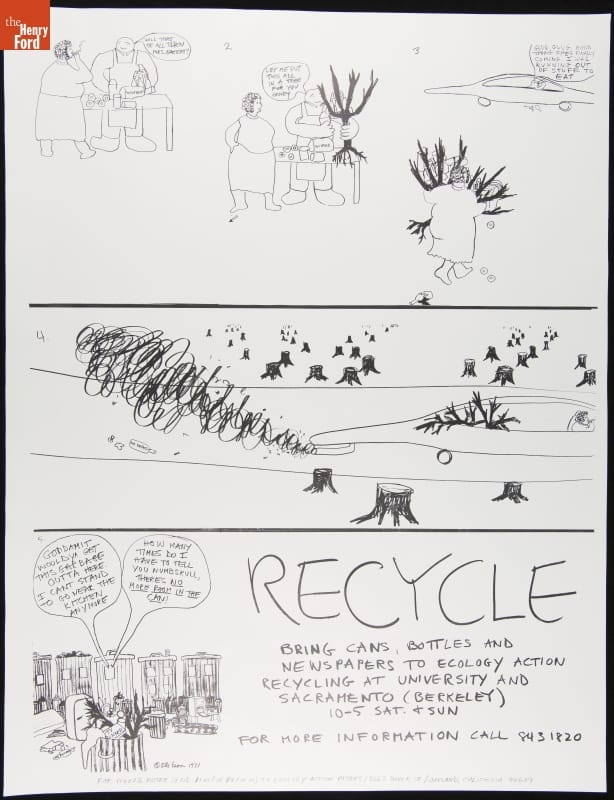

Poster by Eli Leon for Ecology Action, “Recycle” 1971. THF284835

Recycling emerged as a natural outgrowth of Earth Day, but local efforts could not succeed without explanation. First, consumers had to be convinced to save their newspapers, bottles, and cans, and then to make the extra effort to drop them off at centralized locations. This flyer showed how every-day consumer activity (grocery shopping) contributed to deforestation, littering, and garbage pile-up. Everybody could participate in the solution – recycling.

Recycling cost money, and this caused communities to balance what was good for the Earth, acceptable to residents, and possible within available operating funds. Even if customers voluntarily recycled, it still cost money to store recyclables and to sell the post-consumer materials to buyers.

Recycling Bin, Designed for Use in University City, Missouri, 1973. THF181540

City officials and residents in University City, Missouri, started curbside newspaper recycling in 1973, one of the first in the country to do so. Some argued that the city lost money because the investment in staff and trucks to haul materials cost more than the city earned from the sale, but saving the planet, not profit, motivated the effort. Eight years into the program, in 1981, city officials estimated that newspaper recycling kept 85,000 trees from the paper mill.

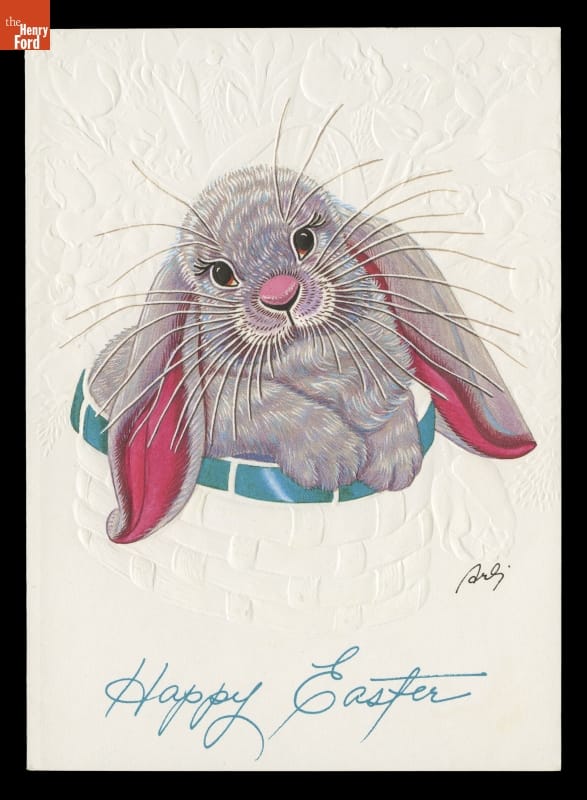

Easter Greeting Card, "Happy Easter," 1989-1990. THF114178

Today, more than 1/3 of post-consumer waste, by weight, is paper. Processing requires energy & chemicals, but recycled paper uses less water and produces less air pollution than making new paper from wood pulp. Maybe you buy greeting cards of 100% recycled paper, like this late 1980s example from our digital collections.

Environmentalism and Vegetable Gardening

Awareness of environmental issues affected the habits and actions of gardeners. Home gardening became an act of self-preservation in the context of Earth Day and environmentalism.

Lyman P. Wood founded Gardens for All in 1971, and the association conducted its first Gallup poll of a representative sample of American gardeners in 1973. It helped document the actions of gardeners, those proactive subscribers to new serials such as Mother Earth News. It confirmed their demographics and their economic investment.

Mother Earth News, 1970. THF290238

Raising vegetables using organic or natural fertilizers and traditional pest control methods became an act of resistance to increased use of synthetic chemical applications as concern about residual effects on human health increased.

How to Grow Vegetables and Fruits by the Organic Method, 1971. THF145272

Interest in organic methods remains high as concern about genetic-engineered foods polarizes consumers. The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines biotechnology broadly. The definition includes plants that result from selective breeding and hybridization, as practiced by Luther Burbank, among others, as well as genetic modification accomplished by inserting foreign DNA/RNA into plant cells. This last became commercially viable only after 1987. These definitions affect seed marketing, as this “organic” Burbank Tomato (not genetically engineered) indicates.

Charles C. Hart Seed Company “Burbank Slicing Tomato” Seed Packet, circa 2018. THF276144

What Gardening Means Today

Gardening as an act of personal autonomy

"Assuming Financial Risk," Clip from Interview with Melvin Parson, April 5, 2019. THF295329

Social justice entrepreneurs believe gardens and gardening can change lives. Learn about the work of Melvin Parson, the Spring 2019 William Davidson Foundation Entrepreneur in Residence at The Henry Ford, in this expert set. You can also learn more from Will Allen in an interview in our Visionaries on Innovation series.

Environmentalism

The 1970 “The Age of Conservation” has changed with the times, but individual acts and world-wide efforts still sustain efforts to “Give the Earth a Chance.” You can learn more about environmentalism over the decades by viewing artifacts here.

To read more about Adam Rome and The Genius of Earth Day: How a 1970 Teach-In Unexpectedly Made the First Green Generation (2013), take a look at this site.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. This post came from a Twitter chat hosted in celebration of Earth Day 2020.

20th century, 1970s, nature, gardening, environmentalism, by Debra A. Reid, #THFCuratorChat

Resilient Foods, Resourceful People

Members of the Woman's National Farm and Garden Association, 1918. THF288950

Members of the Woman's National Farm and Garden Association, 1918. THF288950

Most Americans rely on grocery stores today. Few remember the time when there was constant demand on people to produce and preserve the grain, vegetables and meat they needed to feed themselves.

Over the last few weeks, self-isolation and social distancing have brought into sharp focus the need to plan for your next meal. Do you do it yourself, heading to your cellar to extract the last potatoes or turnips from the bins, or lift the lid off the sauerkraut crock, or pull down a cured ham from the rafters? Probably not. Do you head to the local market or the grocery store and stock up on fresh supplies to see you through for a few days? Or do you dig into the back of your cupboard and pull out a boxed mix or canned goods.

There’s never been a greater time to be resourceful than now. Last week, we donated food from The Henry Ford’s restaurants and cafeteria to Forgotten Harvest to help support our community after our campus closed this month because of COVID-19.

Looking for inspiration to be resourceful in your kitchen? We've dipped into resources and stories from The Henry Ford's collections to try to help. Explore the differences between home cooking and food resourcefulness today and in the past — from farm fresh and family raised to preserved and prepackaged. These digital resources will help you find inspiration whether it’s breakfast, lunch or dinner. Sort through recipe books, dig out that potato — is it a Burbank?! — and season with that essential preservative, salt, reflect and enjoy.

What are you doing in your kitchens right now to make the most of what’s in your cabinets? Share your examples of resourcefulness by tagging your photos and ideas with #WeAreInnovationNation.

Resilient Foods, Resourceful People

Women and the Land: Agricultural Organizations of WWI

Freedom from Want

Mattox Home

Staples

A Versatile Ingredient (Salt)

What If A Potato Could Change the World of Agriculture?

Summer Staples: Tomato and Corn

Eggs

Eggs (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Historic Recipe Bank

Bread & Biscuits

Preservation & Processing Foods

Henry J. Heinz: His Recipe for Success

Canning

Refrigerators

Fresh Paper (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Supply Chains

Horse-Drawn Deliveries

Lunch Wagons: The Business of Mobile Food

Tri-Motor Flying Grocery Store

Alternative Eating & Home Cooking

Farmbot

Food Huggers (as seen on The Henry Ford’s Innovation Nation)

Individual Artifacts

Swanson Frozen Dinners, 1967

Waffle Iron

Victory Gardens

Macaroni

Bean Pot

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment. Did you find this content useful? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

COVID 19 impact, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, philanthropy, food

A Closer Look: The Champion Egg Case Maker

After the Civil War, urban populations swelled. Until this time, farm families had kept flocks of chickens and gathered eggs for their own consumption, but with increased demand for eggs in growing cities, egg farming grew into a specialized industry. Some families expanded egg production at existing farms, and other entrepreneurs established large-scale egg farms near cities and on railroad lines. Networks developed for shipping eggs from farms to buyers – whether wholesalers, retailers, or individuals operating eating establishments.

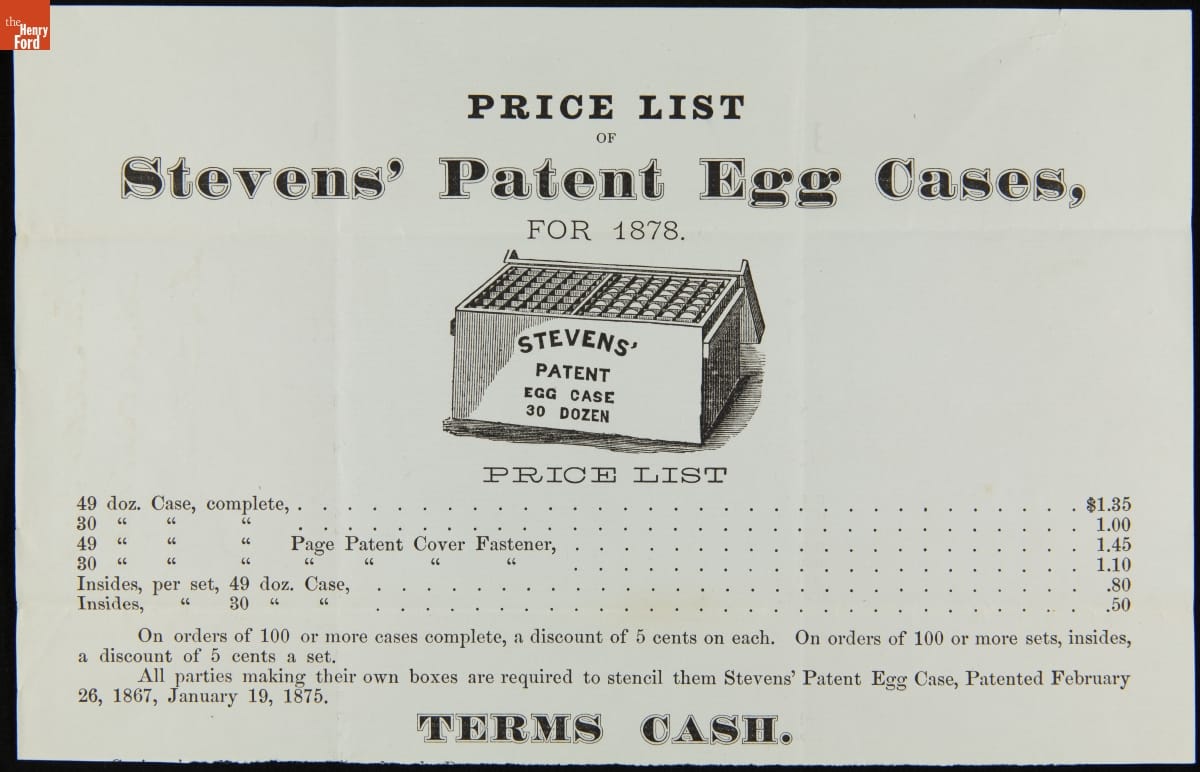

While farmers who sold eggs directly to customers carried their products to market in different ways, sellers who shipped eggs to buyers standardized their containers to ensure a consistent product. The standard egg case became an essential and enduring part of the egg industry.

Egg producers initially used different sizes and types of containers to pack eggs for market. As the egg industry developed, standardized cases that held thirty dozen (360) eggs – like this version first patented by J.L. and G.W. Stevens in 1867 – became the norm. THF277733

Egg distributors settled on a lightweight wooden box to hold 30 dozen (360) eggs. The standard case had two compartments that held a total of twelve “flats” – pressed paper trays that held 30 eggs each and provided padding between layers. Retailers who purchased wholesale cases of eggs typically repackaged them for sale by the dozen (though customers interested in larger quantities could – and still can – buy flats of 30 eggs).

The standard egg case held 12 of these pressed paper trays, or “flats,” which held 30 eggs each. THF169534

Some egg shippers purchased premade egg cases from dedicated manufacturers. Others made their own. Enter James K. Ashley, who invented a machine to help people build egg cases to standard specifications. Ashley, a Civil War veteran, first patented his egg case maker in 1896 and received additional patents for improvements to the machine in 1902 and 1925.

James K. Ashley’s patented Champion Egg Case Maker expedited the assembly of standard egg cases.

Ashley’s machine, which he marketed as the Champion Egg Case Maker, featured three vises, which held two of the sides and the interior divider of the egg case steady. Using a treadle, the operator could rotate them, making it easy to nail together the remaining sides, bottom, and top to complete a standard egg case, ready to be stenciled with the seller’s name and filled with flats of eggs for shipment.

Ashley’s first customer was William Frederick Priebe, who, along with his brother-in-law Fred Simater, operated one of the country’s largest poultry and egg shipping businesses. As James Ashley continued to manufacture his egg case machines (first in Illinois, then in Kentucky) in the early twentieth century, William Priebe found rising success as the big business of egg shipping grew ever bigger.

One of James K. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Makers, now in the collections of The Henry Ford. THF169525

James Ashley received some acclaim for his invention. Ashley’s Champion Egg Case Maker earned a medal (and, reputedly, the high praise of judges) at the St. Louis World's Exposition in 1904. And in 1908, The Egg Reporter – an egg trade publication that Ashley advertised in for more than a decade – described him as “the pioneer in the egg case machine business” (“Pioneer in His Line,” The Egg Reporter, Vol. 14, No. 6, p 77).

While the machine in the The Henry Ford’s collection no longer manufactures egg cases, it still has purpose – as a keeper of personal stories and a reminder of the complex ways agricultural systems respond to changes in where we live and what we eat.

Additional Readings:

- Henry’s Assembly Line: Make, Build, Engineer

- Ford’s Game-Changing V-8 Engine

- Steam Engine Lubricator, 1882

- The Wool Carding Machine

farming equipment, manufacturing, food, farms and farming, farm animals, by Saige Jedele, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture

Freedmen’s Bureau: Exercising Citizenship

President Abraham Lincoln signed The Freedmen’s Bureau Act on March 3, 1865. That Act created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands as part of the War Department. It provided one-year of funding, and made Bureau officials responsible for providing food, clothing, fuel, and temporary shelter to destitute and suffering refugees behind Union lines and to freedmen, their wives, and children in areas of insurrection (in other words, within the Confederate States). The legislation specified the Bureau’s administrative structure and salaries of appointees. It also directed the Bureau to put abandoned or confiscated land back into production by allotting not more than 40 acres to each loyal refugee or freedman for their use for not more than three years, at a rent equal to six percent of its 1860 assessed value, and with an option to purchase. The Bureau assumed additional duties in response to freed people’s goals, namely building schools, negotiating labor contracts, and mediating conflicts.

Lincoln supported the Bureau because it fit his plan to hasten peace and reconstruct the nation, but after Lincoln’s assassination, support wavered. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1866 provided two years of funding. During 1868, increasing violence and for a return to state authority undermined the goals of freed people and the Bureau that worked for them. The Freedmen’s Bureau Act of 1868 authorized only the educational department and veteran services to continue. All other operations ceased effective January 1, 1869.

Collections at The Henry Ford help document public perceptions of the Freedmen’s Bureau as well as actions taken by Bureau advocates. Letters, labor contracts, and newspapers indicate the contests that played out as the Bureau tried to introduce a new model of economic and social justice and civil rights into places where absolute inequality based on human enslavement previously existed. The Bureau did not win the post-war battle for freedmen’s rights. Congress did not reauthorize the Bureau, and it ceased operations in mid-1872.

The Beginning

Bureau appointees went to work at the end of the Civil War in 1865 to serve the interests of four-million newly freed people intent on exercising some self-evident truths itemized in the Declaration of Independence:

That all men are created equal

That they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights

That among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.

Engraved Copy of the 1776 Declaration of Independence, Commissioned by John Quincy Adams, Printed 1823.

With freedom came responsibility to sustain the system of government that “We the People” constituted in 1787, and that the Union victory over secession reaffirmed in 1865. Little agreement over the best course of action existed. The national government extended the blessings of liberty by abolishing slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865. It established the Freedmen’s Bureau which advocated for the general welfare of newly freed people.

Book, "The Constitutions of the United States, According to the Latest Amendments," 1800. THF 155864

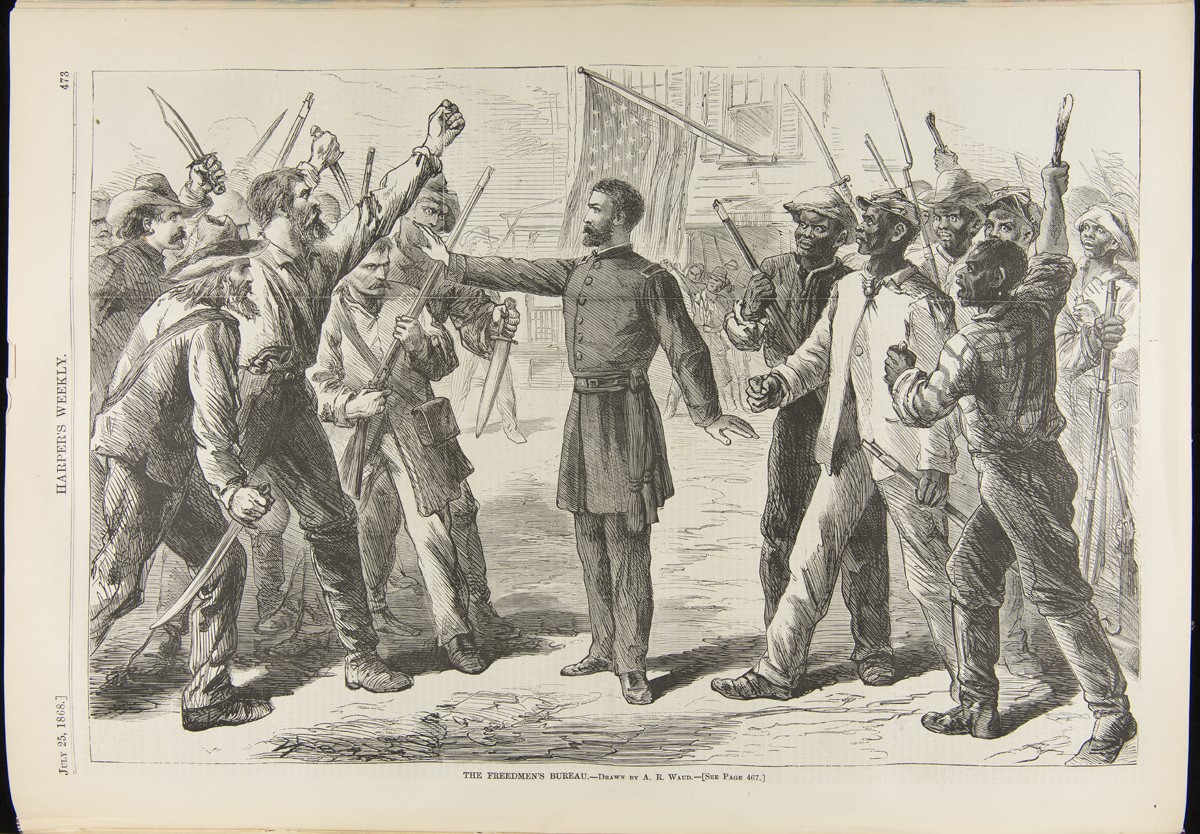

Expanding liberty and justice came at a price, both economic and human. Every time freed people exercised new-found liberty and justice, others resisted, perceiving the expansion of another person’s liberty as a threat to their own. The Bureau operated between these factions, as an 1868 illustration from Harper’s Weekly depicted. The newspaper claimed that the Bureau was “the conscience and common-sense of the country stepping between the hostile parties, and saying to them, with irresistible authority, ‘Peace!’.”

“The Freedmen’s Bureau,” Harper’s Weekly, July 25, 1868, pg. 473. 2018.0.4.38. THF 290299

Economics

Building a new southern economy went hand in hand with expanding social justice and civil rights. Concerned citizens and commanding officers knew that African Americans serving in the U.S. Colored Troops had money to save. They started private banks to meet the need. The U.S. Congress responded with "An Act to Incorporate the Freedman's Savings and Trust Company." Lincoln signed the legislation on March 3, 1865, the same day he signed “An Act to Establish a Bureau for the relief of Freedmen and Refugees.” Agents of the public Freedmen’s Bureau worked closely with staff at the private Freedman’s Bank because freed people needed the economic stability the bank theoretically provided.

At least 400,000 people, one tenth of the freed population, had an association with a person who opened a savings account in the 37 branches of the savings bank that operated between 1865 and 1874. This included Amos H. Morrell, whose daughter’s heirs resided in the Mattox House. Soldiers listed on the Muster Roll of Company E, 46th Regiment of United States Colored Infantry, also appear in records of the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. Charles Maho, a private in Company E, 46th USCT, opened an account on August 13, 1868. He worked in a tobacco factory at the time. His brother in arms, James Parvison/Parkinson, also a private, opened an account on December 1, 1869 and his estranged wife, Julia Parkerson opened an account on May 14, 1870.

Mattox Family Home, circa 1880

Freedmen’s Bureau officials encouraged deposits into the Freedmen’s Bank. This helped freed people become accustomed to saving the coins they earned, literally the coins that symbolized their independence as wage earners. Sadly, Bureau officials often assured account holders that their investments were safe. The deposits were not protected by the national government, however, and when the bank closed in 1874 it left depositors penniless and petitioning for return of their investments.

One-cent piece. Minted in 1868. THF 173625 (front) and THF 173624 (back)

Three-cent piece (made of nickel). Minted in 1865. THF 173623 (front) and THF 173622 (back).

The U.S. Congress authorized the Bureau to collect and pay out money due soldiers, sailors, and marines, or their heirs. Osco Ricio, a private in Company E, 46th U.S. Colored Infantry, who enlisted for three years in 1864, but was mustered out in 1866, made use of this service in his effort to secure $187 due him.

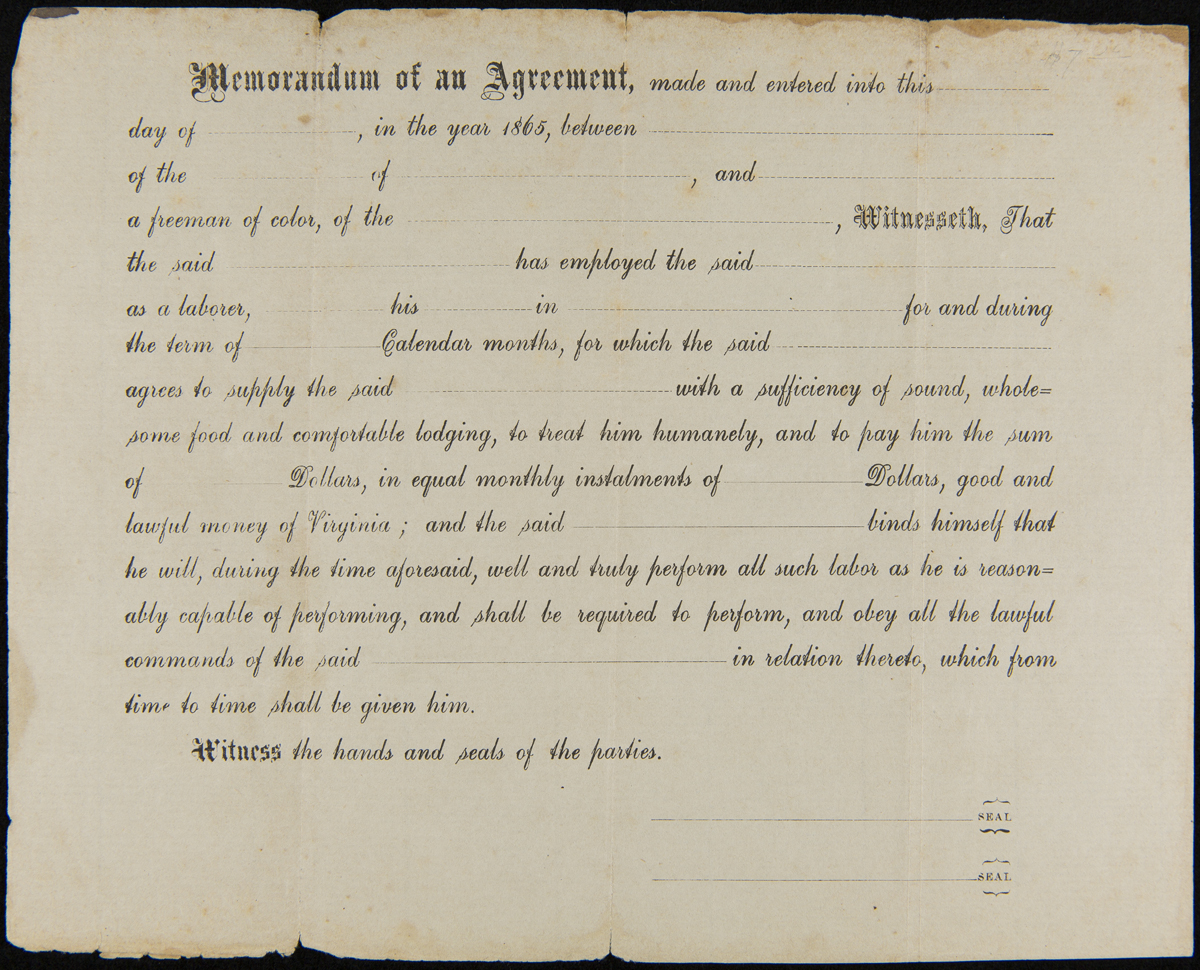

Freedmen’s Bureau staff mediated between freed people and employers, negotiating contracts that specified work required, money earned, and protection afforded if employers reneged on the agreement. A blank form, printed in Virginia in 1865, included language common to an indenture – that the employer would provide “a sufficiency of sound, wholesome food and comfortable lodging, to treat him humanely, and to pay him the sum of _____ Dollars, in equal monthly instalments of ____ Dollars, good and lawful money in Virginia.”

Freedman's Work Agreement Form, Virginia, 1865 Object ID 2001.48.18. THF 290704

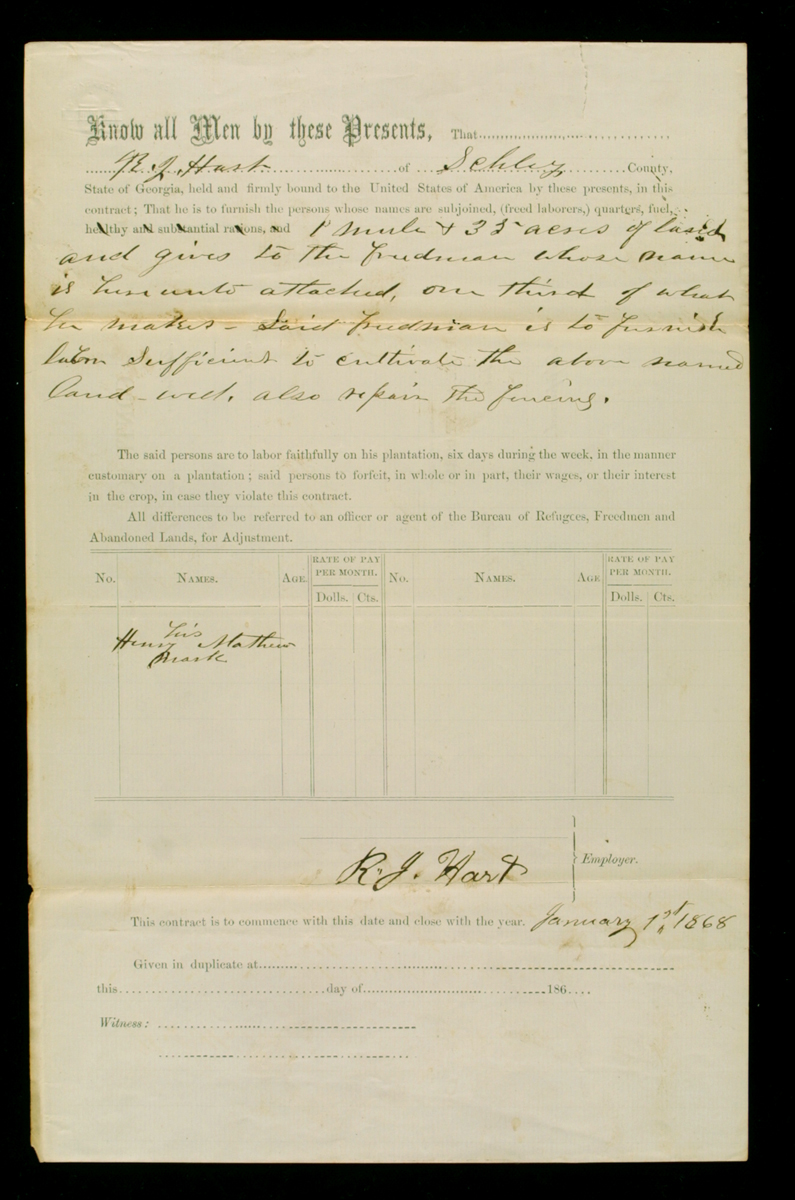

Another pre-printed form reinforced terms of enslavement, that the work should be performed “in the manner customary on a plantation,” even as it confirmed the role of Freedmen’s Bureau agents as adjudicator. Freedman Henry Mathew, and landowner R. J. Hart, in Schley County, Georgia, completed this contract which legally bound Hart to furnish Mathew “quarters, food, 1 mule, and 35 acres of land” and to “give. . . one-third of what he [Mathew] makes.” This type of arrangement became the standard wage-labor contract between landowners and sharecroppers, paid for their labor with a share of the crops grown on the land.

Freedman's Contract for a Mule and Land, Dated January 1, 1868. THF 8564

Many criticized sharecropping as another form of unfree labor rather than as a fair labor contract. Close reading confirms the inequity which often took the form of additional work that laborers performed but that benefitted owners. In the case of Hart and Mathew, Mathew had to repair Hart’s fencing which meant that Mathew realized only one-third return on his labor investment in the form of a crop perhaps more plentiful because of the fence. Hart claimed the other two-thirds of the crop plus all of the increased value of fencing.

Education

Freed people wanted access to education to learn what they needed to make decisions as informed and productive citizens.

Harper’s Weekly, a New York magazine, often featured freedmen’s schools that resulted from a cooperative agreement between the Freedmen’s Bureau and the American Missionary Association (AMA), based in New York. A reporter informed readers on June 23, 1866 that “the prejudice of the Southern people against the education of the ‘negroes’ is almost universal.” Regardless, freed people needed schools, teachers, and institutes to train teachers. The Freedmen’s Bureau and its partners committed their resources in support of this cause.

Commentary accompanying an illustration of the “Primary School for Freedmen” indicated that the school building was dilapidated and owned by someone who wanted rid of the school, but the students were eager to learn and as capable as other students of their age in New York public schools.

“Primary School for Freedmen, in Charge of Mrs. Green, at Vicksburg, Mississippi, Harper’s Weekly, June 23, 1866, pg. 392 (bottom), story on pg. 398. THF 290712

School curriculum often emphasized agricultural and technical training. The “Freedmen’s Farm School,” located near Washington, D.C., also known as the National Farm-School, taught orphans and children of U.S. Colored Troops reading, writing and arithmetic, standard primary school subjects. Students also cultivated a one-hundred-acre farm. The combination compared to a new effort launched with the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 to create a system of colleges, federally funded but operated at the state level to train students in agricultural and mechanical subjects. The combination could help students realize the American dream – owning and operating their own farm. While the system of land-grant colleges grew steadily during Reconstruction, the freedmen’s schools faced opposition locally and at the state level. Increasingly educators turned to philanthropists to fund education for freed people.

Struggles

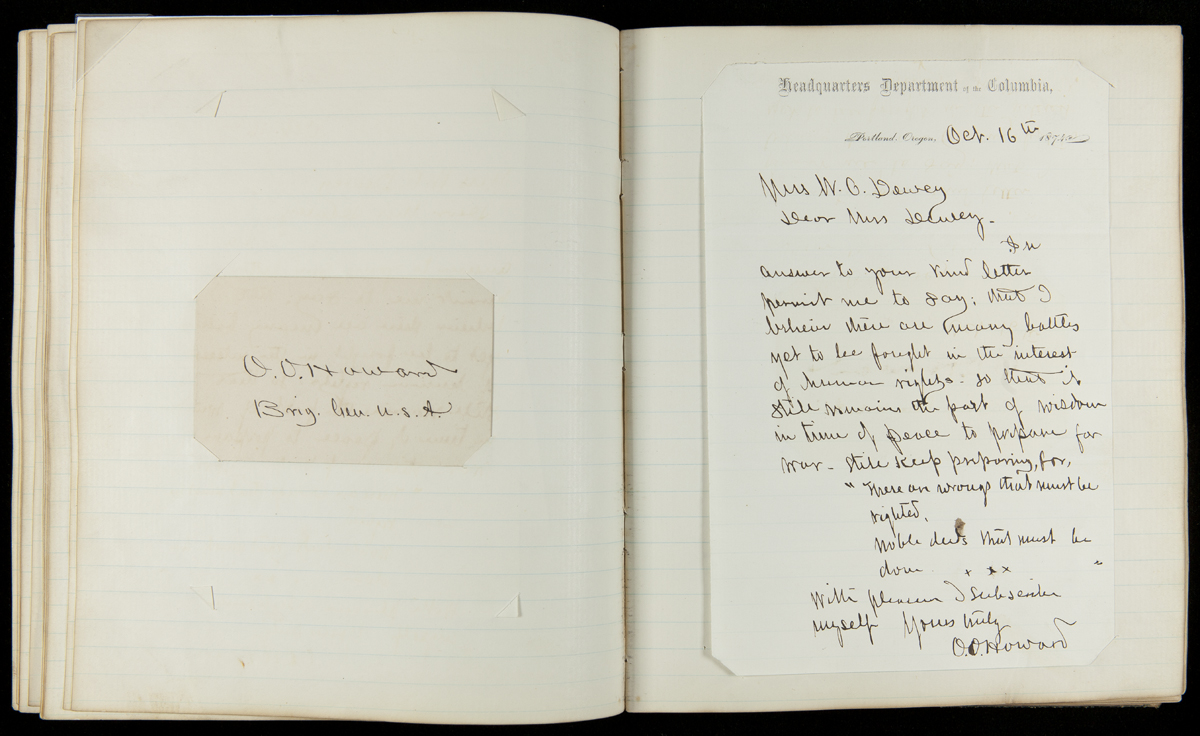

The individuals appointed to direct the Freedmen’s Bureau often had military experience. Brigadier General Oliver Otis Howard served in the Union Army and gained a reputation as a committed abolitionist if not a strong officer. President Andrew Johnson appointed him the first Commission of the Bureau, and he remained in that position until the Bureau closed in 1872. Two years later Howard lamented lost opportunities: “I believe there are many battles yet to be fought in the interest of human rights”….“There are wrongs that must be righted. Noble deeds that must be done.”

Many shared Howard’s frustrations with the lack of public support for freed people’s goals. They also resented the obstructions that thwarted those goals. Newspaper reporting, such as the regular features in Harper’s Weekly, emphasized the good work of the Freedmen’s Bureau, but reporting also threatened projects aimed at sustaining the momentum.

Henry Wilson, a Republican Senator from Massachusetts, sought equality for African Americans. He took a correspondent to the Republican, a newspaper in Springfield, Massachusetts, to task for publishing misinformation about the extent of congressional fundraising for political purposes, and for downplaying the need for sharing facts with voters, especially the 700,000 Southerners newly enfranchised after ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. Wilson explained that hundreds of thousands of documents, possible through the congressional fundraising, could educate voters about issues and prepare them for the upcoming election. Without donations from U.S. congressmen, Wilson believed such efforts would fail.

The End

The short life but complicated legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau leaves much to ponder. The Bureau, as a part of the War Department, and then an independent national agency, mediated local conflict and supported local education. This occurred at an exceptional time as the Union began rebuilding the nation in 1865. Then, the Republican party interpreted the U.S. Constitution as a mandate for the national government to protect civil rights broadly defined. The Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868, incorporated newly freed people as full citizens. Most believed that the Bureau had no more work to do, and Congress did not reauthorize it after July 1872. Those who favored the Bureau lamented its abrupt end and believed that much remained to be done to open the American experiment in equal rights to all.

Debra Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

Sources and Further Reading

- African American Records: Freedmen’s Bureau, National Archives and Records Administration

- Carpenter, John A. Sword and Olive Branch: Oliver Otis Howard (1999)

- Cimbala, Paul A. The Freedmen's Bureau: Reconstructing the American South after the Civil War (2005)

- Foner, Eric. Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1988).

- Litwack, Leon F. Been in the Storm So Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979).

- McFeely, William S. Yankee Stepfather: General O.O. Howard and the Freedmen (1994).

- Osthaus, Carl R. Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud: A History of the Freedman's Savings Bank (1976)

- Oubre, Claude F. Forty Acres and a Mule: The Freedmen’s Bureau and Black Land Ownership (2012).

- Washington, Reginald. “The Freedman's Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research,” Federal Records and African American History (Summer 1997, Vol. 29, No. 2)

1870s, 1860s, 19th century, Civil War, by Debra A. Reid, African American history

Small Objects with Big Stories

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

Timber Scribe: A small tool, a timber scribe, helps inform us about resourcefulness and entrepreneurship.

The Oxford English Dictionary confirms use of the term “timber scribe” by 1858 as “a metal tool or pointed instrument for marking logs and casks.” Another tool, a “race-knife” (also spelled rase knife) performed a similar function, “marking timber,” but the tools differed in detail.

The race knife had a “bent-over, sharp lip for scribing,” according to Edward H. Knight who compiled the Practical Dictionary of Mechanics, a nearly 8,000-page behemoth containing 20,000 subjects and around 6,000 illustrations, published in 1877. The timber scribe included two pieces with bent-over sharp lips as well as a point. The combination made it possible to scribe Arabic numbers, not just gouge Roman numerals, into logs and casks and timber, as shown below.

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

This tool has a wooden handle, a brass band that helped stabilize the wooden end where the forged steel was inset into the wooden handle, and the steel point with a cutter/gouge and separate “bent-over sharp lip”/gouge Dimensions: Length 7.25 inches; Height 2 inches; Width 1 inch. Object ID: 2017.0.34.625

Simply stated, a timber scribe included the components of the race knife. Lumbermen, shipbuilders, house wrights and carpenters, coopers, and surveyors, all used the timber scribe to make uniform marks on wood, but they could also use the elongated cutter/gouge to make free-hand marks. They used the race knife to make free-hand marks.

Appearances mattered. The timber scribe at The Henry Ford combines three natural materials – iron/steel, brass, and wood – all processed and refined in ways that make the tool pleasing to the eye, and useful to the woodsman or craftsman. The maker chamfered the edges of the wooden handle and scribed the brass collar.

An 1897 catalog from a Detroit hardware distributor, the Charles A. Strelinger Company, advertised a “rase knife or timber scribe.” The company sold three variations: a large size (though the catalog provided no dimensions), a small size, and a pocket rase knife. The large timber scribe included all three steel components (point with cutter gouge and “bent-over sharp lip” gouge) while the small version included just two of the three (point and gouge). The pocket rase knife likely consisted of just the gouge, which folded into the wooden handle of the knife, as seen below.

Rase Knife or Timber Scribe. Detail from Wood Workers’ Tools: Being a Catalogue of Tools, Supplies, Machinery, and Similar Goods used by Carpenters, Builders, Cabinet Makers, Pattern Makers, Millwrights, Carvers, Ship Carpenters, Inventors, Draughtsmen, and [also] all “Wood Butchers” not included in Foregoing Classification and in Manufactories, Mills, Mines, etc., etc. Detroit Michigan: Charles A. Strelinger & Company, 1897, page 662. In the collection of the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

The tool in The Henry Ford's collection compares to the large timber scribe illustrated in Strelinger & Company’s 1897 catalog. The tool’s dimensions (7.25 inches long) inform us about the size of a “large” scribe.

Charles A. Strelinger was born in Detroit in 1856. The 1897 catalog Charles A. Strelinger Company indicated that the company had 30 years of experience in manufacturing and selling tools, supplies and machinery. Strelinger’s approach to advertising his wares through print media indicated how little change occurred in the tool business. The front page of the catalog had a blank space to write in the date, and, as he explained in “This Year’s Catalogue”: “our 1895 catalogue is also our 1896-’97-’98, and perhaps, 1899 catalogue. If we were selling Seeds and Plants, Ladies’ Hats and Bonnets, Patent Medicines, etc., we would, doubtless, find it necessary to issue a new catalogue every year, but our goods are of a stable nature, changes are comparatively few, and we are not warranted to going to the expense of printing a new book every year.”

The timber scribe and the Strelinger Company catalog confirm the need for specialized tools that serve many in various wood-working trades. The Company was resourceful in advertising, because the hand tools in woodworking were remarkably standardized by the late-nineteenth century and remained useful despite industrialization.

Debra A. Reid is Curator, Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford.

The Henry Ford received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) in 2017 to support a three-year project to conserve, rehouse, and digitize thousands of objects. This is work, supported through IMLS’s Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, will continue over three years as The Henry Ford consolidates offsite collections into a new location on campus. The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via THF's Digital Collections.”

A series of blogs shares the stories of small items that tell big stories of innovation, ingenuity, and resourcefulness, and that relate to other collections and interpretation at The Henry Ford.

Solving a Collections Mystery with IMLS

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

Susan Bartholomew, Collections Specialist here at The Henry Ford, is busy cataloging objects from The Henry Ford's Collections Storage Building (CSB). A three-year grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) Museums for America Collections Stewardship project, supports conserving, rehousing, and digitizing thousands of objects currently housed in several bays of the CSB.

As the grant narrative explains, the IMLS funding supports a “critical element in a major institutional project: the consolidation of The Henry Ford's off site collections into a new location on campus.” The work “will improve the physical condition of the project artifacts through conservation treatment, rehousing, and removal to improved environments.” Finally, IMLS funding “will facilitate collections access through the creation of catalog records and digital images, available to all via The Henry Ford's digital collections.”

Occasionally Susan comes upon an artifact that needs additional explanation to accurately catalog it, such as this one. Here's what we knew upon examination:

- It's 16" long, 7" wide

- Has a smooth wooden handle

- Is bent and welded iron

- There's a ringed brass flange positioned to reduce wear where the metal is imbedded into the organic material.

The questions we then ask: What is this instrument? What purpose does it serve?

We turned to our horse experts with the Ford Barn team in Greenfield Village to help us understand its use.

A steady diet of oats, grass, and hay wears a horse’s teeth down as they age. Persistent grinding of food can leave sharp burrs or edges on the outside of their molars. Untreated, this causes pain when the horse chews, and they lose weight.

Farmers and veterinarians used this instrument (called a “gag” or speculum) to hold a horse’s mouth open as they floated the horse’s teeth to balance their bite. Floating helps a horse maintain a healthy bite in their senior years.

A person (farmer or veterinarian) would insert the “gag” into the horse’s mouth, holding it by the handle. Then, the farmer/veterinarian would pull downward on the handle which “encouraged” the horse’s mouth to open. The oval area provided a window through which to place the float (a rasp used to file down the sharp edges).

The device proved useful when treating younger horses with other dental issues, too. Today caring for aging horses still requires floating and balancing their teeth. Caregivers still use a speculum to hold the horse’s mouth open, and to keep their head steady during floating and balancing, but the instruments today have padding to reduce stress on the horse’s jaw during the procedure.

Thanks to the IMLS for providing the invaluable funding to help make this exploration of animal care possible.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Jim Slining is Curator of Museum Collections at Tillers International.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, IMLS grant, healthcare, farm animals, by Jim Slining, by Debra A. Reid, agriculture, #Behind The Scenes @ The Henry Ford

Winter Nature Studies

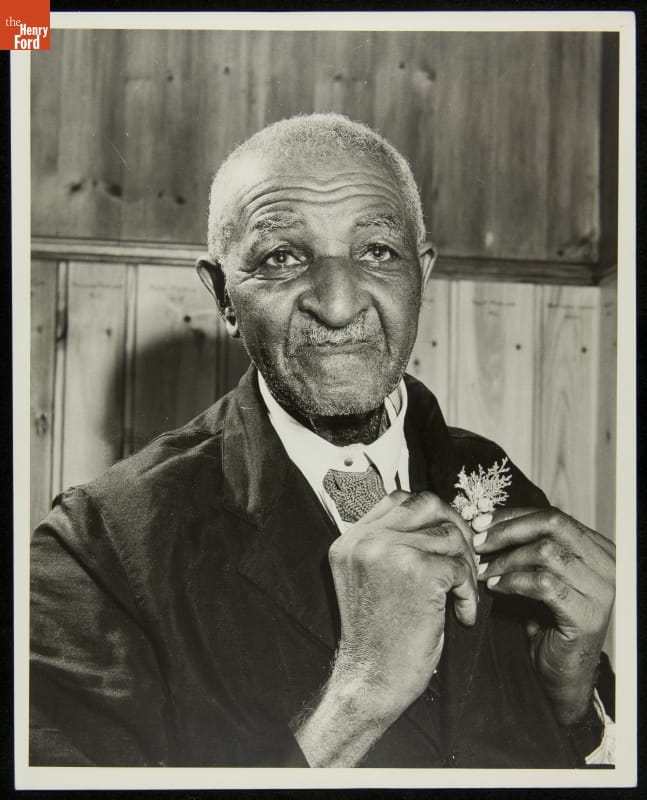

THF213753 / George Washington Carver at Dedication of George Washington Carver Cabin, Greenfield Village, 1942.

On this day in 1946, George Washington Carver Recognition Day was designated by a joint act of the U.S. Congress and proclaimed by President Harry S. Truman. Carver died just three years earlier on this day in 1943.

Immediately, public officials and the news media began to celebrate his life and create lasting reminders of his work in education, agricultural science, and art. Carver, mindful of his own legacy, had already established the Carver Foundation during the 15th annual Negro History Week, on February 14, 1940, to carry on his research at Tuskegee. It seems fitting to pay respects to Carver on his death day by taking a closer look at the floral beautis that Carver so loved, and that we see around us, even during winter.

Carver recalled that, “day after day I spent in the woods alone in order to collect my floral beautis” [Kremer, ed., pg. 20]. He believed that studying nature encouraged investigation and stimulated originality. Experimentation with plants “rounded out” originality, freedom of thought and action.

THF213747 / George Washington Carver Holding Queen Anne's Lace Flowers, Greenfield Village, 1942.

Carver wanted children to learn how to study nature at an early age. He explained that it is “entertaining and instructive, and is the only true method that leads up to a clear understanding of the great natural principles which surround every branch of business in which we may engage” (Progressive Nature Studies, 1897, pg. 4). He encouraged teachers to provide each student a slip of plain white or manila paper so they could make sketches. Neatness mattered. As Carver explained, the grading scale “only applies to neatness, as some will naturally draw better than others.”

Neatness equated to accuracy, and with accuracy came knowledge. Farm families could vary their diet by identifying additional plants they could eat, and identify challenges that plants faced so they could correct them and grow more for market.

Carver understood how the landscape changed between the seasons, and exploring during winter was just as important as exploring during summer. Thus, it is appropriate to apply Carver’s directions about observing nature to the winter landscape around us, and to draw the winter botanicals that we see, based on directions excerpted from Carver’s Progressive Nature Studies (1897). (Items in parentheses added to prompt winter-time nature study - DAR and DE, 3 Jan 2018.)

- Leaves – Are they all alike? What plants retain their leaves in winter? Draw as many different shaped leaves as you can.

- Stems – Are stems all round? Draw the shapes of as many different stems as you can find. Of what use are stems? Do any have commercial value?

- Flowers (greenhouses/florists) – Of what value to the plant are the flowers?

- Trees – Note the different shapes of several different trees. How do they differ? (Branching? Bark?) Which trees do you consider have the greatest value?

- Shrubs – What is the difference between a shrub and a tree?

- Fruit (winter berries) – What is fruit? Are they all of value?

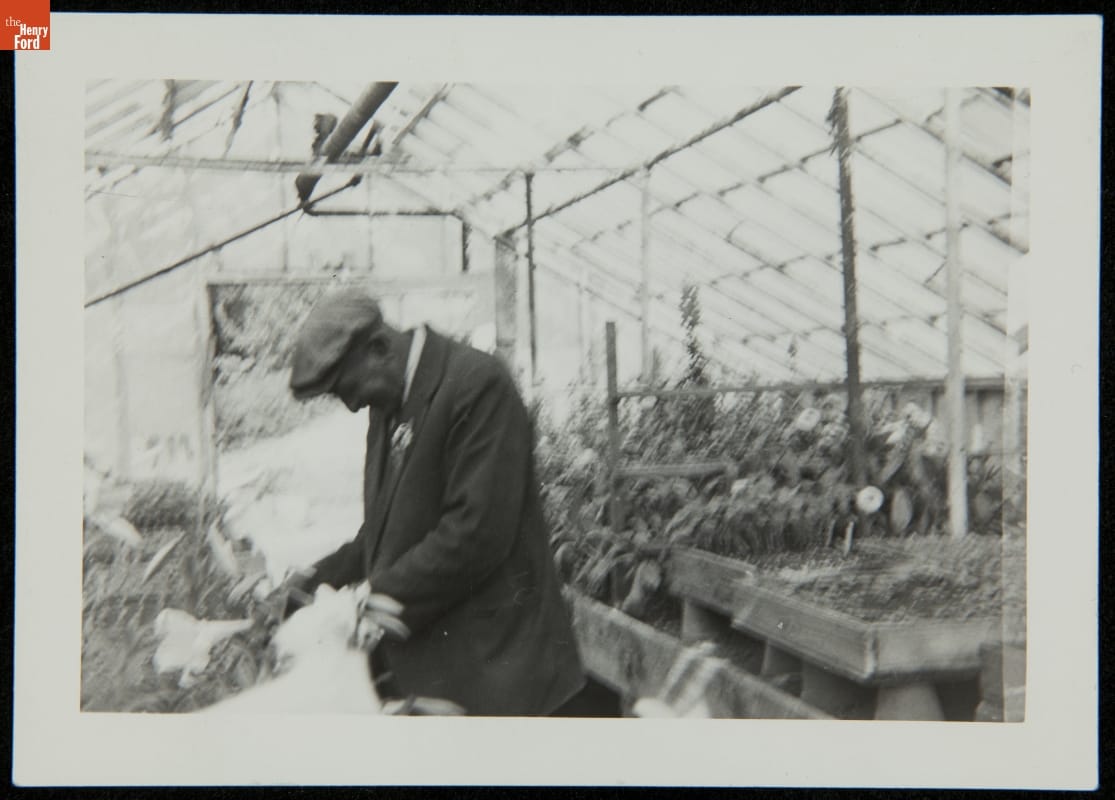

Carver worked in greenhouses and encouraged others to use greenhouses and hot beds to start vegetables earlier in the planting system. The sooner farm families had fresh vegetables, the more quickly they could reduce the amount they had to purchase from grocery stores, and the healthier the farm families would be.

THF213726 / George Washington Carver in a Greenhouse, 1939.

In 1910, Carver included directions for work with nature studies and children’s gardens over twelve months. Selections from “January” suitable for nearly all southern states” included:

- Begin in this month for spring gardening by breaking the ground very deeply and thoroughly

- Clear off and destroy trash (plant debris) that might be a hiding place for noxious insects.

- Cabbages can be put in hot beds, cold frames, or well-protected places.

- Grape vines, fruit trees, hedges and ornamental trees should receive attention (pruning, fertilizing)

- Both root and top grafting of trees should be done.

THF213314 / Pamphlet, "Nature Study and Children's Gardens," by George Washington Carver, circa 1910.

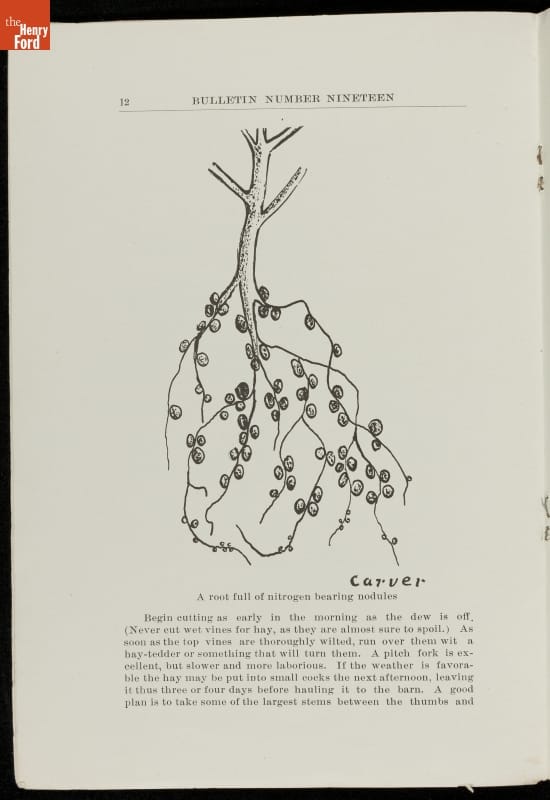

Carver illustrated his own publications, basing his botanical drawings on what he observed in his field work. He conveyed details that his readers needed to know, be they school children tending their gardens, or farm families trying to raise better crops.

THF213278 / Pamphlet, "Some Possibilities of the Cow Pea in Macon County, Alabama," by George Washington Carver, 1910 / page 12.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

Edible wild botanicals, also known as weeds, appeared in late winter. Carver encouraged everyone from his students at Tuskegee to Henry Ford to consumer more wild greens year round, but especially in late winter when greens became a welcome respite from root crops and preserved meats which dominated winter fare. His pamphlet, Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace, prepared during World War II, featured numerous drawings of edible wild botanicals, also called weeds. Americans could contribute to the war effort by diversifying their diets with these greens that sprouted in the woods during the late winter and early spring. Carver illustrated each wild green, including dandelion, wild lettuce, curled dock, lamb’s quarter, and pokeweed. Following the protocol used in botanical drawing, he credited the source, as he did with several illustrations identified as “after C.M. King.” This referenced the work of Charlotte M. King, who taught botanical drawing at Iowa State University during the time of Carver’s residency there, and who likely influenced Carver’s approach to botanical drawing. King’s original of the “Small Pepper Grass” drawing appeared in The Weed Flora of Iowa (1913), written by Carver’s mentor, botanist Louis Hermann Pammel.

THF213586 / Pamphlet, "Nature's Garden for Victory and Peace," by George Washington Carver, March 1942.

To learn more about Carver, consult these biographies:

- Hersey, Mark D. My Work is that of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. George Washington Carver: A Biography. Santa Barbara, Cal.: Greenwood, 2011.

- Kremer, Gary R. ed. George Washington Carver in His Own Words. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1987.

- McMurry, Linda O. George Washington Carver, Scientist and Symbol. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

To read more about Carver and Nature Study, see:

- Carver, G. W. Progressive Nature Studies. (Tuskegee Institute Print, 1897), Digital copy available at Biodiversity Heritage Library, https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/98621#page/132/mode/1up

- Harbster, Jennifer. “George Washington Carver and Nature Study,” blog, March 2, 2015, https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2015/03/george-washington-carver-and-nature-study/

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment at The Henry Ford. Deborah Evans is Master Presenter at The Henry Ford.

winter, nature, George Washington Carver, education, by Debra A. Reid, by Deborah Evans, art, agriculture, African American history

Ford Radio and Fordlandia

Henry Ford used wireless radio to communicate within Ford Motor Company (FMC) starting after October 1, 1919. This revolutionary new means of communication captured Ford’s interest because it allowed him to transmit messages within his vast operation. By August 1920, he could convey directions from his yacht to administrators in FMC offices and production facilities in Dearborn and Northville, Michigan. By February 1922, Ford’s railroad offices and the plant in Flat Rock, Michigan were connected, and by 1925, the radio transmission equipment was on Ford’s Great Lake bulk haulers and ocean-going vessels. Historian David L. Lewis claimed that “Ford led all others in the use of intracompany radio communications” (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 311).

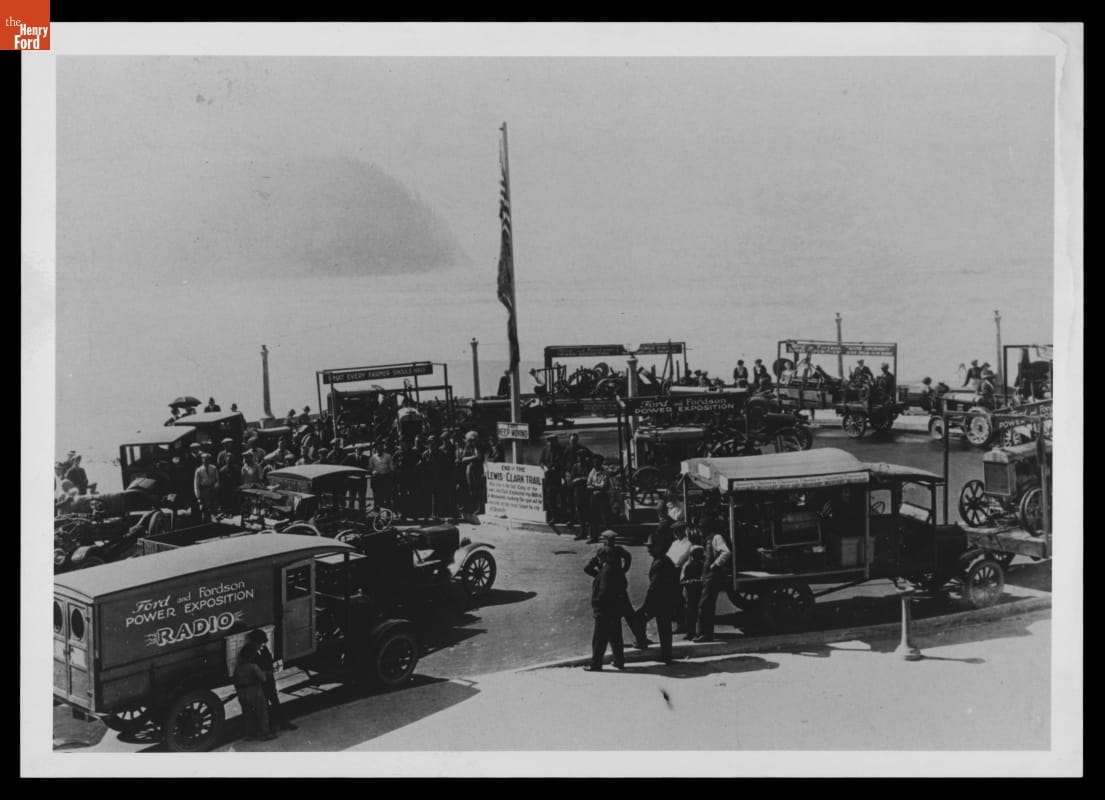

Ford Motor Company also used radio transmissions to reach external audiences through promotional campaigns. During 1922, FMC sales branches delivered a series of expositions that featured Ford automobiles and Fordson tractors. An article in Motor Age (August 10, 1922) described highlights of the four-month tour of western Oregon:

“The days are given over to field demonstrations of tractors, plows and implements, while at night a radio outfit that brings in the concerts from the distant cities and motion pictures from the Ford plant, keep an intensely interested crowd on the grounds until the Delco Light shuts down for the night.”

The Ford Radio and Film crew that broadcast to the Oregon crowds traveled in a well-marked vehicle, taking every opportunity available to inform passers-by of Ford’s investment in the new technology – radio – and the utility of new FMC products. Ray Johnson, who participated in the tour, recalled that he drove a vehicle during the day and then played dance music in the evenings as a member of the three-piece orchestra, “Sam Ness and his Royal Ragadours.”

Ford and Fordson Power Exposition Caravan and Radio Truck, Seaside, Oregon, 1922 . THF134998

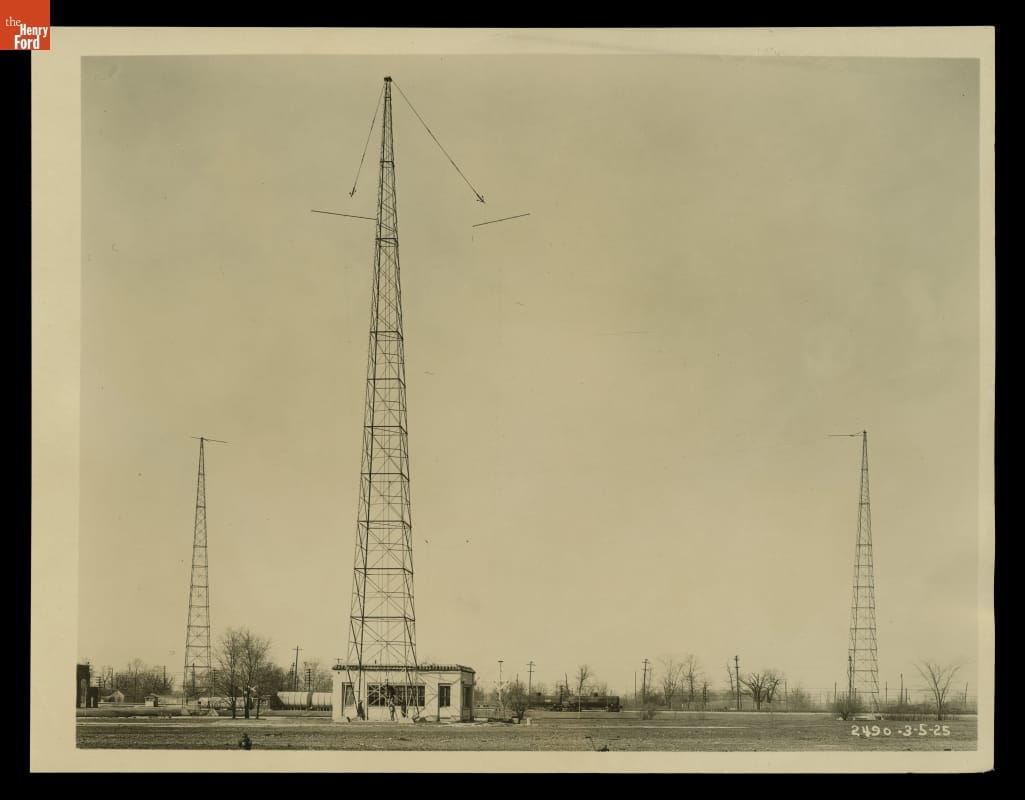

In 1922, Intra-Ford transmissions began making public broadcasts over the Dearborn’s KDEN station (call letters WWI) at 250-watts of power, which carried a range of approximately 360 meters. The radio station building and transmission towers were located behind the Ford Engineering Laboratory, completed in 1924 at the intersection of Beech Street and Oakwood Boulevard in Dearborn.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, March 1925. THF134748

Staff at the station, conveying intracompany information and compiled content for the public show which aired on Wednesday evenings.

Ford Motor Company Radio Station WWI, Dearborn, Michigan, August 1924. THF134754

The station did not grow because Ford did not want to join new radio networks. He discontinued broadcasting on WWI in early February 1926 (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 179).

Ford did not discontinue his intracompany radio communications. FMC used radio-telegraph means to communicate between the head office in Dearborn and remote locations, including, Fordlandia, a 2.5-million-acre plantation that Ford purchased in 1927 and that he planned to turn into a source of raw rubber to ease dependency on British colonies regulated by British trade policy.

Brazil and other countries in the Amazon of South American provided natural rubber to the world until the early twentieth century. The demand for tires for automobiles increased so quickly that South American harvests could not satisfy demand. Industrialists sought new sources. During the 1870s, a British man smuggled seeds out of Brazil, and by the late 1880s, British colonies, especially Ceylon (today Sri Lanka) and Malaysia, began producing natural rubber. Inexpensive labor, plus a climate suitable for production, and a growing number of trees created a viable replacement source for Brazilian rubber.

British trade policies, however, angered American industrialists who sought to establish production in other places including Africa and the Philippines. Henry Ford turned to Brazil, because of the incentives that the Brazilian government offered him. His goals to produce inexpensive rubber faced several hurdles, not the least of which was overcoming the traditional labor practices that had suited those who harvested rubber in local forests, and the length of time it took to cultivate new plants (not relying on local resources).

Ford built a production facility on the Tapajós River in Brazil. This included a radio station. The papers of E. L. Leibold, in The Henry Ford’s Benson Ford Research Center, include a map with a key that indicated the “proposed method of communication between Home Office and Ford Motor Company property on Rio Tapajos River Brazil.” The system included Western Union (WU) land wire from Detroit to New York, WU land wire and cable from New York to Para, Amazon River Cable Company river cable between Para and Santarem, and Ford Motor Company radio stations at each point between Santarem and the Ford Motor Company on Rio Tapajós. Manual relays had to occur at New York, Para, and Santarem.

Map Showing Routes of Communication between Dearborn, Michigan and Fordlandia, Brazil, circa 1928. THF134693

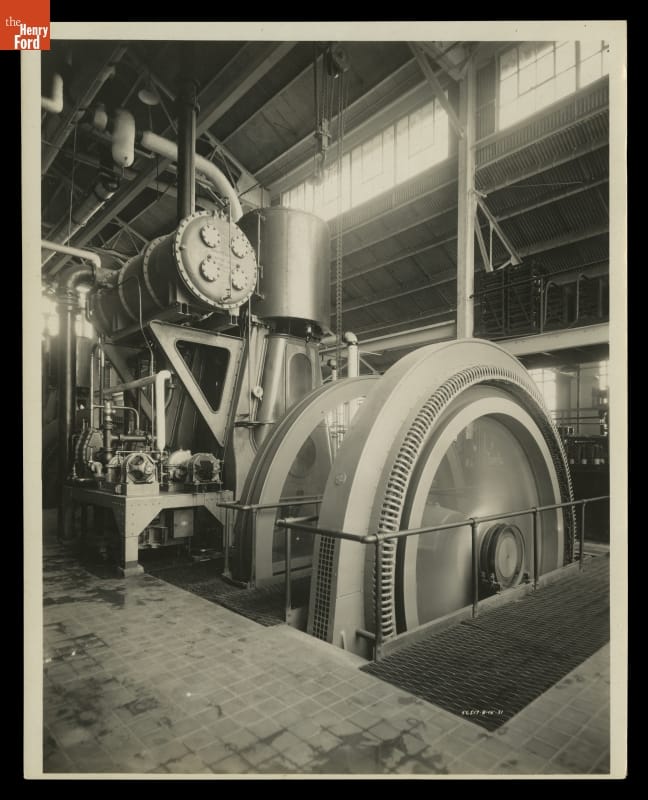

Ford officials studied the federal laws in Brazil that regulated radio and telegraph to ensure compliance. Construction of the power house and processing structures took time. The community and corporate facilities at Boa Vista (later Fordlandia) grew. By 1931, the power house had a generator that provided power throughout the Fordlandia complex.

Generator in Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134711

Power House and Water Tower at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134714

Lines from the power house stretching up the hill from the river to the hospital and other buildings, including the radio power station. The setting on a higher elevation helped ensure the best reception for radio transmissions.

Sawmill and Power House at Fordlandia, Brazil, 1931. THF134717

Workers built the radio power house, which held a Delco Plant and storage batteries, and the radio transmitter station with its transmission tower. The intracompany radio station operated by 1929.

Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134697

Radio Transmitter House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134699

Storage Batteries in Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134701

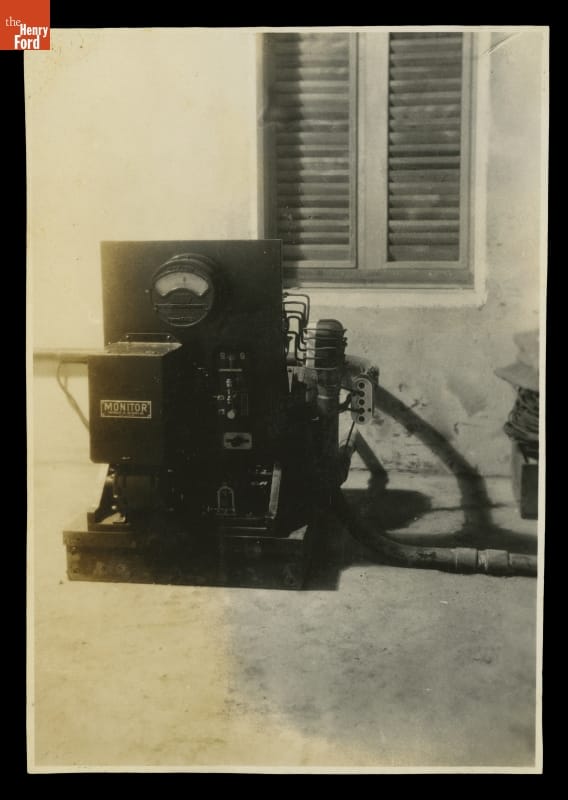

Delco Battery Charger for Radio Power House, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134703

Radio Power House Motor Generator Set, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134705

The radio power house is visible at the extreme left of a photograph showing the stone road leading to the hospital (on an even higher elevation) at Fordlandia.

Stone Road Leading to Hospital, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134709

Radio Transmitter Station, Fordlandia, Brazil, 1929. THF134707

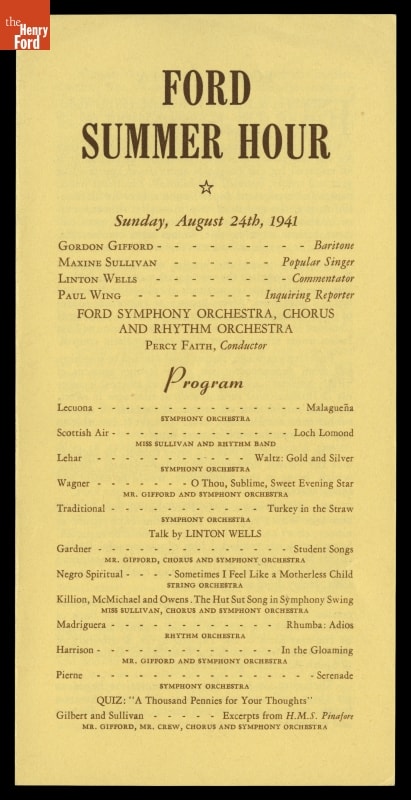

Back at FMC headquarters in Dearborn, Ford announced in late 1933 that he would sponsor a program on both NBC and CBS networks. The Waring show aired two times a week between 1934 and 1937, when Ford pulled funding. Ford also sponsored World Series broadcasts. The most important radio investment FMC made, however, was the Ford Sunday Evening Hour, launched in the fall of 1934. Eighty-six CBS stations broadcast the show. Programs included classical music and corporate messages delivered by William J. Cameron, and occasionally guest hosts. Ford Motor Company printed and sold transcripts of the weekly talks for a small fee.

On August 24, 1941 Linton Wells (1893-1976), a journalist and foreign correspondent, hosted the broadcast and presented a piece on Fordlandia.

Program, "Ford Summer Hour," Sunday, August 24, 1941. THF134690

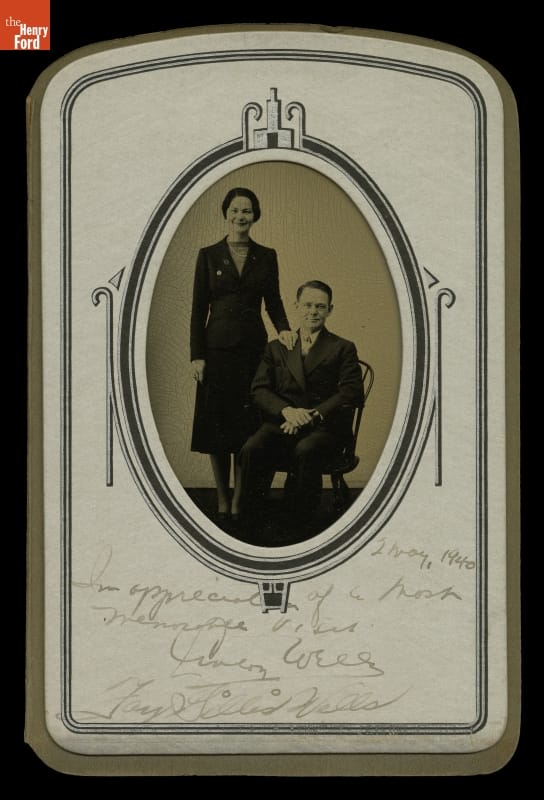

Linton Wells was not a stranger to Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village, he and his wife, Fay Gillis Wells, posed for a tintype in the village studio on 2 May 1940.

Tintype Portrait of Linton Wells and Fay Gillis Wells, Taken at the Greenfield Village Tintype Studio, circa 1940. THF134720

This radio broadcast informed American listeners of the Fordlandia project, in its 16th year in 1941. Wells summarized the products made from rubber (by way of an introduction to the importance of the subject). He described the approach Ford took to carve an American factory out of an Amazonian jungle, and the “never-say-quit” attitude that prompted Ford to re-evaluate Fordlandia, and to trade 1,375 square miles of Fordlandia for an equal amount of land on Rio Tapajós, closer to the Amazon port of Santarem. This new location became Belterra. Little did listeners know the challenges that arose as Brazilians tried to sustain their rubber production, and Ford sought to grow its own rubber supply.

By 1942, nearly 3.6 million trees were growing at Fordlandia, but the first harvest yielded only 750 tons of rubber. By 1945, FMC sold the holdings to the Brazilian government (The Public Image of Henry Ford, 165).

The Ford Evening Hour Radio broadcasts likewise ceased production in 1942 after eight years and 400 performances.

Learn more about Fordlandia in our Digital Collections.

Debra A. Reid is Curator of Agriculture and the Environment; Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication and Information Technology; and Jim Orr is Image Services Specialist at The Henry Ford.

Sources

- Relevant collections in the Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford, Dearborn, Michigan.

- Grandin, Greg. Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City. Picador. 2010.

- Lewis, David L. The Public Image of Henry Ford: An American Folk Hero and His Company. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 1976.

- Frank, Zephyr and Aldo Musacchio. “The International Natural Rubber Market, 1870-1930.″ EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 16, 2008.

South America, 20th century, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, technology, radio, Michigan, Henry Ford, Fordlandia and Belterra, Ford Motor Company, communication, by Kristen Gallerneaux, by Jim Orr, by Debra A. Reid