Posts Tagged by kristen gallerneaux

Highlights from CES 2017

The Henry Ford sponsored the 2017 CES Innovation Awards, visible here.

If you explore the Consumer Electronic Show “by the numbers,” the tallies show an influx of 177,000 people into one small area of Las Vegas. Over the course of four days, the visiting population (equivalent to that of a small city) attempts to make its way through nearly 2.5 million square feet of exhibitions presented by almost 4000 different companies. By no means to be shrugged off is the 35 miles of walking I did over the five days that I was there; despite all of this trekking across three separate venues, I failed to see everything.

For those unfamiliar with the event, CES is a global trade show produced by the Consumer Technology Association. Every January, established companies and young startups alike launch and demonstrate the latest in consumer technology. At this event, some of the biggest names in innovation display alongside next-generation technology developers.

Many artifacts from The Henry Ford’s collections, including those above, were first launched at CES.

In 2017, CES reached its 50th anniversary. To celebrate this milestone, an exhibition of devices first introduced to the public at the show were on display. The list of technology unveiled at CES over the years is impressive: Sony’s U-matic VCR (1970), the Sony/JVC personal Camcorder (1981), Philips’ CD player (1981)—as well as a lineage of media formats like the laserdisc (1978), CD (1981), DVD (1996), and Blu-Ray (2004). Many items that were introduced to the marketplace at CES also appear in The Henry Ford’s collections: Atari’s version of Home Pong (1975), the Commodore 64 (1982), the Nintendo Entertainment System (1985), the Sony Walkman (1980), and many cellphones from the 1980s that seem laughably large to us now such as the Motorola “brick phone” and wearable StarTAC flip-phone.

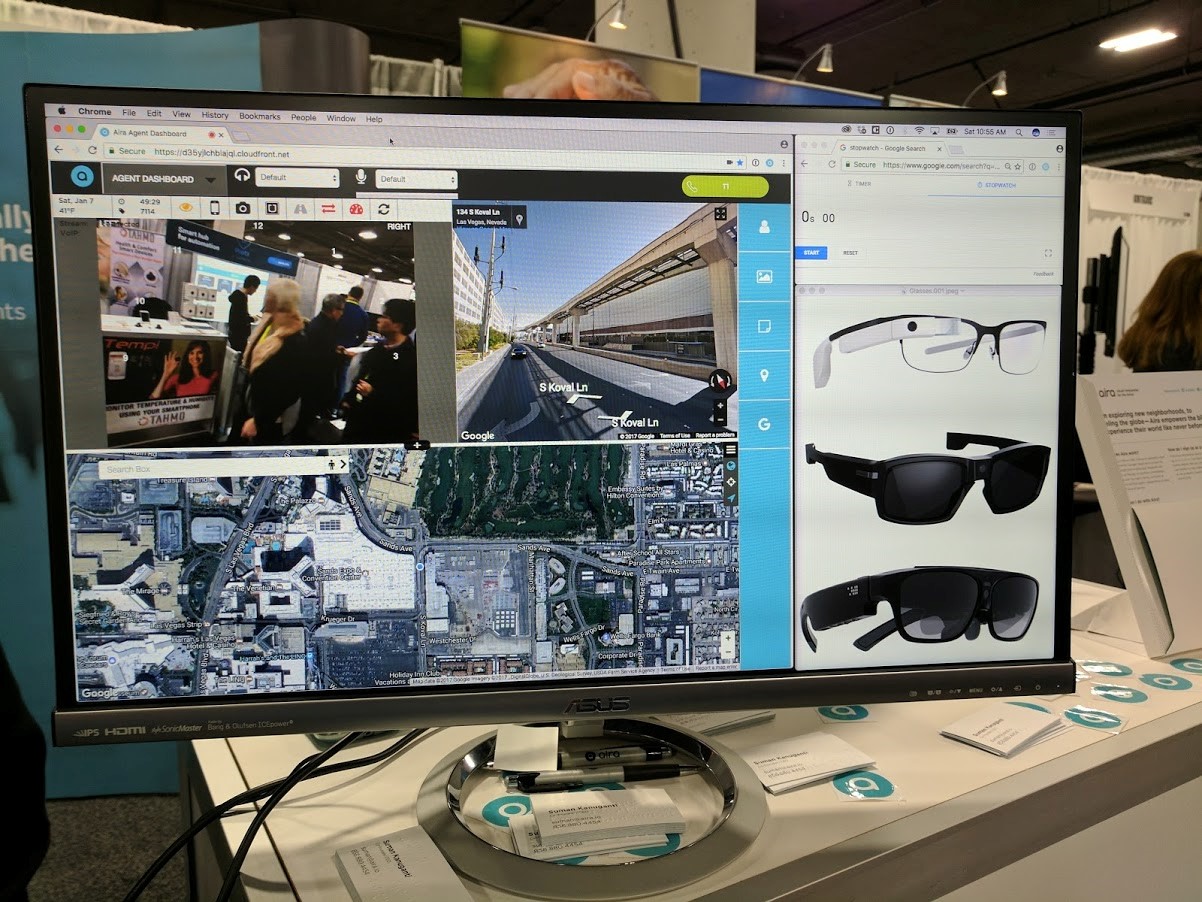

The Aira service is a digital visual interpreter for the blind.

The Henry Ford also sponsored the CES 2017 Innovation Awards—“an annual competition honoring outstanding design and engineering in consumer technology products.” Several winners in the Accessibile Tech category were of interest, given The Henry Ford’s archival collections documenting a visit from Helen Keller, blind workers at the Ford Rouge, TTY/TDD devices, or vibrating alarm clocks for the deaf and hard of hearing. The Aipoly application uses artificial intelligence and a smartphone camera to help the blind identify objects around them; the Aira service is a similar real-time visual interpreter that makes use of wearable devices like Google Glass to do the same. The ReSound ENZO2 hearing aid also makes use of the Bluetooth technology embedded in smartphones, allowing people to adjust noise cancellation levels in crowded area from an app on their phone—or to stream phone calls and music directly to their assistive devices.

The REMI smart alarm clock helps children to develop healthy sleep patterns. (Image courtesy of Urbanhello)

Increased awareness of digital citizenship and responsibility were also evident in the Innovation Awards—an important theme that will continue to affect our technology collections as we continue to grow them. The XooLoo Digital Coach rethinks parental controls over teen’s technology use. Rather than simply limiting content, this application allows parents to ethically participate and learn about the patterns of use in their children’s digital lives. The app does many things, such as log the amount of time spent on websites and social media, allows parents to turn off digital access during mealtimes—yet respects privacy by not exposing messages or geo-tracking. Other examples include the Motorola Moto-Mods series, which allows a Moto Z phone to transform into a boombox or a big screen projector—turning the solitary viewing or listening of media stored on smartphones into outward, shared experiences. The pleasant-looking Remi smart alarm clock by UrbanHello visually trains children how to create better sleep routines, which results in healthy growth, moods, and learning. Its glowing face flips from sleepy to happy mode, indicating when it is acceptable for a child to get out of bed; additional custom programming tells children when to brush teeth, plays calming music or can act as a monitoring device.

The Navdy heads-up display allows drivers to see basic information linked from cell phone apps through a transparent screen on their dashboard. (Image courtesy of Navdy)

Continue Reading

Reaching for Mars

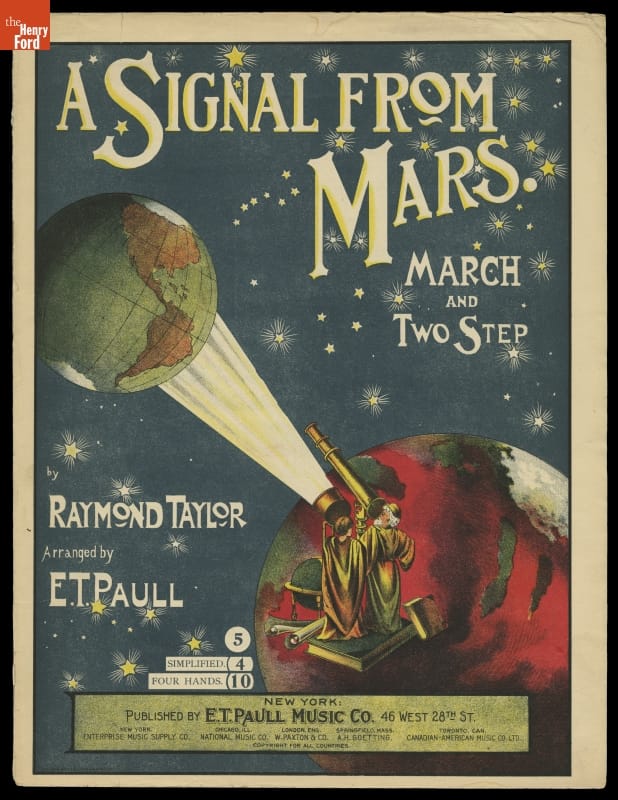

Raymond Taylor and E.T. Paull’s “A Signal From Mars March and Two-Step,” 1901 imagines two inhabitants of Mars using a signal lamp to communicate with Earth. THF129403

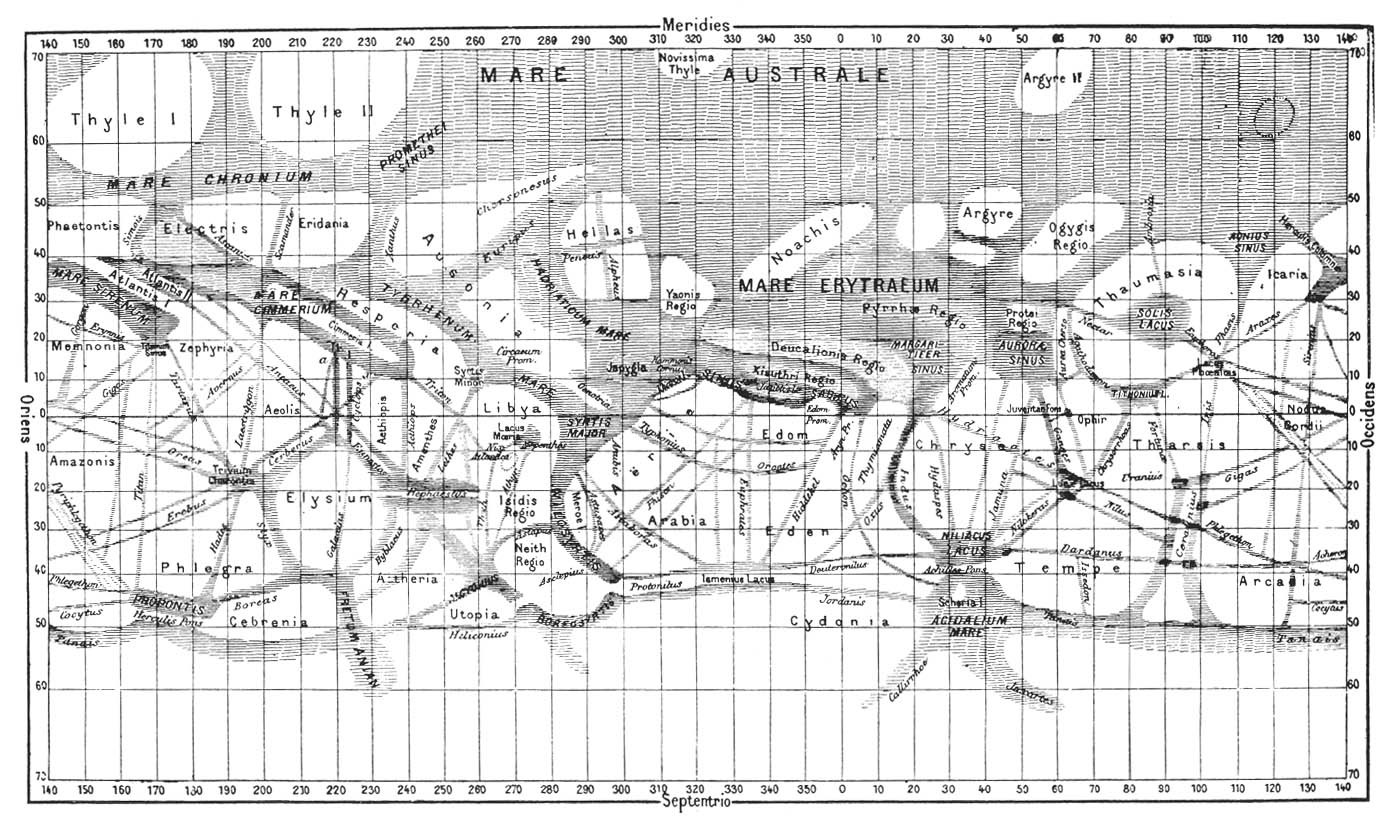

The concept of "life on Mars" and "Martian Fever" was not incited in the pages of the tabloid magazine Weekly World News—but actually reaches much further back to 1877—with Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli. The astronomer himself was not to blame: a single word in his report—canali, which is Italian for “channels”—was misinterpreted to mean "canal" once translated into English. In Schiaparelli’s time, telescopes became more advanced and powerful, allowing him to make detailed maps of the planet’s surface. At the time of this mapping, Mars was in “opposition,” bringing the planet into close alignment with Earth for easier observation. While creating his maps, however, Schiaparelli fell victim to an optical illusion. He perceived straight lines crisscrossing the surface of the planet, which he included in his records, assigning them the names of rivers on Earth. These were the canali—and the source of a misunderstanding which morphed into a self-perpetuating legend about intelligent, ancient, canal-building Martian lifeforms.

Giovanni Schiaparelli’s Map of Mars (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons).

Much to Schiaparelli’s annoyance, the American astronomer Percival Lowell continued to pursue this "life on Mars" theory. Beginning in 1895, Lowell published a trilogy of books about the “unnatural features” he saw through his telescope in Flagstaff, Arizona. He created his own maps of the planet, much of which Schiaparelli believed to be pure fantasy. In reality, the imagery Lowell was seeing was likely caused by diffraction illusion in his equipment. Lowell was not alone in popularizing the concept of an intelligent Red Planet. The astronomer, psychical researcher, and early science fiction writer Camille Flammarion published The Planet Mars in 1892, which collected his archival research and historic literature exploring the idea of an inhabited planet. In 1899, Nikola Tesla claimed to have tapped into intelligent radio signals from Mars; in 1901 the director of Harvard’s Observatory Edward Charles Pickering claimed to have received a telegram from Mars.

In 1901—the year that Raymond Taylor and E.T. Paull’s "A Signal from Mars" sheet music was published—"Mars Fever" had officially taken hold, as scientists and enthusiasts alike actively explored the potential for two-way communication with Mars. This piece of music, made in tribute to the planet, is a prime example of the exoticism of science, space travel, and speculation about the limits of technology (along with a few missteps) colliding with future-forward, popular, and artistic culture. Amazing Stories, September 1950. THF344586

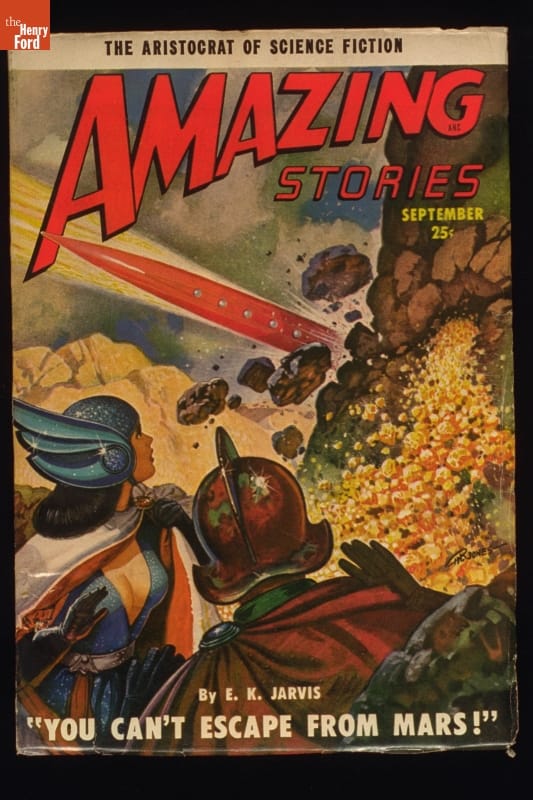

Amazing Stories, September 1950. THF344586

Speculative thinking about Mars did not end in 1901—it has continued to provide a source of inspiration and exploration for both popular and scientific cultures. The Red Planet and its hypothetical inhabitants often appeared in early pulp and science fiction magazines like Amazing Stories and Astounding Stories. The first issue of Amazing Stories was published in April 1926 by inventor Hugo Gernsback, and was the first magazine to be fully dedicated to the genre of science fiction. Gernsback himself is credited as the “father” of science fiction publishing—or, as he called it, “scientification.” The magazine introduced readers to far-reaching fantasies with journeys to internal worlds like Jules Verne’s “Trip to the Center of the Earth,” and explorations of other dimensions and galaxies, time travel, and the mysterious powers of the human mind. Throughout its publication of over 80 years, Amazing Stories included many fictional accounts of Mars, including H.G. Wells’s “War of the Worlds,” Cecil B. White’s “Retreat to Mars,” pictured here, E.K. Jarvis’s “You Can’t Escape from Mars!”

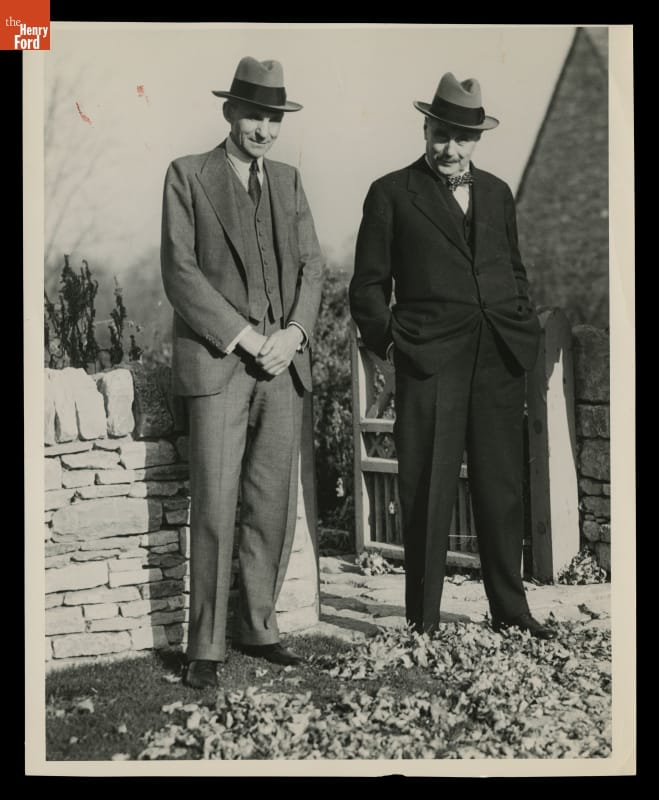

Standing left to right are H.G. Wells and Henry Ford at Cotswold Cottage, Greenfield Village, 1931. This photograph was taken 7 years before the infamous 1938 radio broadcast of Wells’s War of the Worlds. This radio-play used media as an all-too-effective storytelling device, inciting a public panic about an alien invasion in the process. THF108523

Standing left to right are H.G. Wells and Henry Ford at Cotswold Cottage, Greenfield Village, 1931. This photograph was taken 7 years before the infamous 1938 radio broadcast of Wells’s War of the Worlds. This radio-play used media as an all-too-effective storytelling device, inciting a public panic about an alien invasion in the process. THF108523

In 1924, with Mars once again in opposition to Earth, a new round of astronomical experiments and observations emerged. In order to test theories of advanced cultures inhabiting the planet, the inventor Charles Francis Jenkins and astronomer David Peck Todd were commissioned by the US military to conduct a study to “listen to Mars.” For the purposes of this experiment, Jenkins created an apparatus called the “radio photo message continuous transmission machine,” capable of creating visual records of radio phenomena on a long strip of photographic paper. Jenkins’s device was connected to an ordinary SE-950 NESCO radio receiver, serving as the “listening ear” in this experiment. Any incoming signal would trigger a flash of light on the paper, creating black waveform-like lines and thus revealing any chatter of alien radio waves.

The Army and Navy proceeded to silence radio activity for short periods over the three days of Mars’s closest course, believing that anyone who was bold enough to defy military-ordered radio silence would surely be extraterrestrial in origin. The Chief of US Naval Operations, Edward W. Eberle, sent this telegram on August 22nd:

7021 ALNAVSTA EIGHT NAVY DESIRES COOPERATE ASTRONOMERS WHO BELIEVE POSSIBLE THAT MARS MAY ATTEMPT COMMUNICATION BY RADIO WAVES WITH THIS PLANET WHILE THEY ARE NEAR TOGETHER THIS END ALL SHORE RADIO STATIONS WILL ESPECIALLY NOTE AND REPORT ANY ELECTRICAL PHENOMENON UNUSUAL CHARACTER AND WILL COVER AS WIDE BAND FREQUENCIES AS POSSIBLE FROM 2400 AUGUST TWENTY FIRST TO 2400 AUGUST TWENTY FOURTH WITHOUT INTERFERRING [sic.] WITH TRAFFIC 1800[1]

Radio Receiver, Type SE-950, Used by Charles Francis Jenkins in Experiment Detecting Radio Signals from Mars. THF156814

When the paper was developed, the researchers were surprised to find that it contained images. These graphics were interpreted by the public to be “messages” composed of dots and dashes and “a crudely drawn face” repeating down the thirty-foot length of film. Jenkins, however, feared that his machine would be perpetrated as a hoax, so when the films were released he did so with this caveat: “Quite likely the sounds recorded are the result of heterodyning, or interference of radio signals.” While the popular press used these images as confirmation of life on Mars (in fact, this 1924 experiment has appeared as “evidence” in the tabloid, Weekly World News), the scientific community provided logical explanations: static discharge from a passing trolley car, malfunctioning radio equipment, or the natural symphonic radio waves produced by Jupiter. The SE-950 radio used by Jenkins in this experiment is now part of The Henry Ford’s collection: a simple rectangular wood box with knobs and dials that easily hides its deeper history as part of an experiment to communicate with Mars.

From Schiaperelli to Lowell; from the adventure tales of H.G. Wells to the first science fiction magazines of Hugo Gernsback; from a curious piece of turn-of-the-century sheet music to an even stranger experimental radio—Mars has acted as an inspirational and problematic site for creative and scientific pursuits alike. In July of 1964, the fly-by images gathered by the spacecraft Mariner 4 put an end to the most far-flung theories about the planet. As Mariner 4 transmitted images back to Earth, there were no signs of canals, channels—or a populated planet. And finally, in recent years, technological innovation has allowed our knowledge of Mars to grow at a rapid pace, with NASA’s on-planet rover missions and SpaceX’s Falcon and Dragon vehicle programs. Martians or not, despite the fact that the Red Planet lingers an average of 140 million miles away from Earth, it continues to broadcast an inspirational signal of astounding strength, which reaches straight into the human imagination.

Kristen Gallerneaux is the Curator of Communication and Information Technology, The Henry Ford.

([1] Telegram from the Secretary of the Navy to All Naval Stations Regarding Mars, August 22, 1924, Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, 1784-2000, ARC Identifier 596070, National Archives and Records Administration.)

20th century, 19th century, technology, space, radio, popular culture, communication, by Kristen Gallerneaux

History Currently in the Making

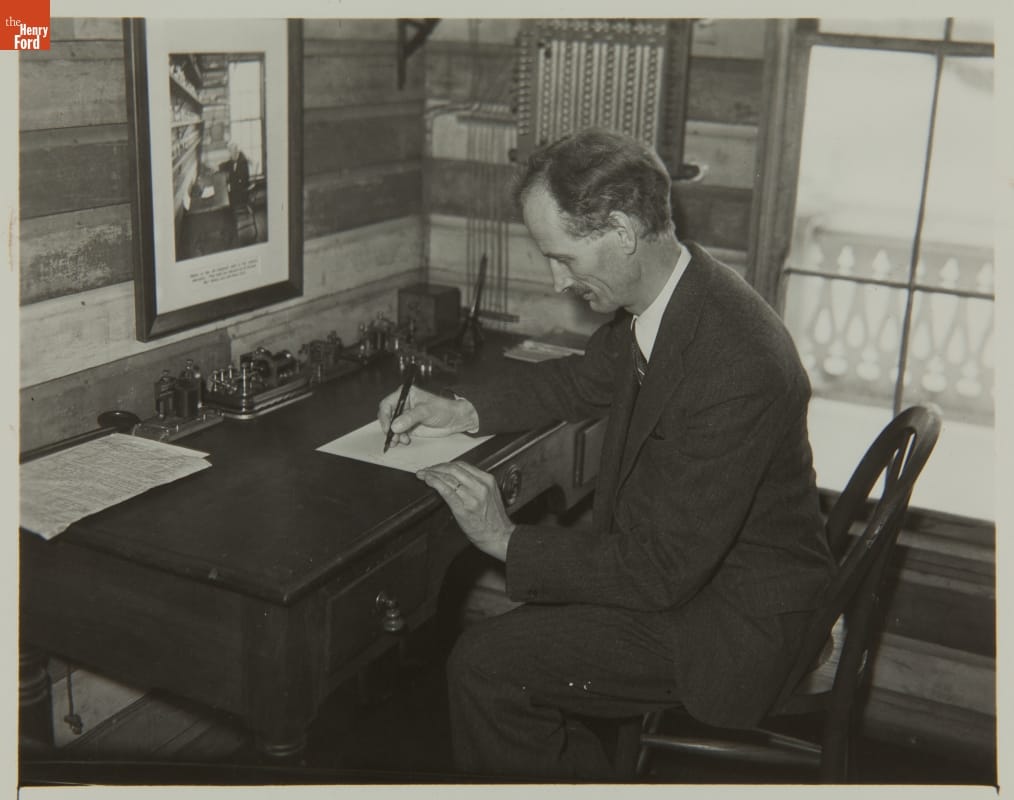

Balloonist Jean Piccard Visiting Menlo Park Laboratory in Greenfield Village, November 1933. THF231520

Earlier this week, Bertrand Piccard, great-nephew of Jean Piccard, finished a team attempt to fly the first solar-powered airplane to successfully circumnavigate the world by landing where the journey started in Abu Dhabi. The Piccard family name is one well known in the collections of The Henry Ford - our collection contains a shortwave radio receiver, custom-built by William Duckwitz for ground communication during the Piccard Stratosphere Flight. The knobs, wires and tubes are typical of a DIY ethos. In 1934, a lightweight metal gondola—carrying the husband and wife exploration team Jean and Jeanette Piccard—rose up from the ground at Ford Airport. The gondola was carried aloft by a hydrogen-filled balloon, (safely) crash-landing over 250-miles away later that day, in Cadiz, Ohio.

Who was manning the gondola below the hydrogen-filled balloon? Jeannette Piccard, a streetwise woman with impressive credentials. She was the first woman to be licensed as a balloon pilot and became the first American woman to enter the stratosphere and, technically speaking, space. Piccard once said: “When you fly a balloon, you don’t file a flight plan; you go where the wind goes. You feel like part of the air. You almost feel like part of eternity, and you just float along.”

To see more artifacts related to Jean and Jeannette Piccard’s stratosphere flight, take a look at our digital collections. You can learn more about Bertrand Piccard’s solar-powered airplane mission here.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

Broken Toys and Lots of Noise

At Maker Faire Detroit 2016, Drew Blanke—more formally known as “Dr. Blankenstein”—will arrive, trailing a rolling suitcase full of broken toys and noise-making creations along behind him. Over the weekend of July 30-31, 2016, Blanke will hold workshops to teach people how to “up-cycle electronics into one-of-a-kind 21st century art.” He asks that guests interested in participating in the workshop bring along broken electronics from home—to “open them, inspect them, and learn from them.” He will also have a few of his own creations available for hands-on demonstrations.

This will be Dr. Blankenstein’s first appearance at Maker Faire Detroit, but he is no stranger when it comes to providing engaging circuit-bending workshops. Kristen Gallerneaux, curator at The Henry Ford, first encountered Blanke at Moogfest 2014, where she saw him demonstrate a musical calculator programmed to play a song by the band Kraftwerk. What else could the song have been, but Pocket Calculator? For fans of synthesized music, his homage was a crowd-pleaser. Blanke has also appeared at World Maker Faire in Queens, NY, and returned to Moogfest 2016 to provide a series of all-ages hands-on workshops.

On Sunday, July 31st, at 2:45pm, Dr. Blankenstein will give a talk in the museum’s Drive-In Theatre called “Circuit Bending & the Art of Electronic Discovery: Open It, Inspect It, LEARN IT!”

Our Curator of Communications and Information Technology, Kristen Gallerneaux, caught up with Dr. Blankenstein for an interview.

How did your love of synthesized music begin? Are there any historic innovators that you would say are direct inspirations on what you do, and how you think about sound design?

I am not sure the exact moment when I began to love synthesizers, but I can tell you it most certainly started in the early 1980s. It wasn’t as much a love for the instrument at first as it was the wonderful sounds they were able to make. I think of music from films such as Tron, Close Encounters of the Third Kind & Breakin’, sound effects and theme songs from TV shows such as Nightrider, CHiPs and Star Trek, and 1980s music such as Kraftwerk, New Wave and early Rap all left a huge impact on me. I can’t leave out Michael Jackson and breakdance music either, I was a mini Breakdancer at the time thanks to Mom & Michael Jackson. Older dancers called me Kid Fresh (LOL). All of these elements created a need to know more about how these sounds were created. I knew there was something different about them versus say a guitar, flute or drums etc. Even at the young age of 5, I knew I wanted to know more.

As for inspirational innovators that I have been influenced by in my later years, I would have to point to Bob Moog and Herb Deutsch. The work I do and the work they did (although similar in nature) is much different in style, but I connect deeply with the passion and creativity that was alive between the two of them. It’s almost like the Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak of the synthesizer world, both such amazing and inspiring American dream stories. It’s almost impossible to not be inspired by them.

Dr. Blankenstein is pictured here demonstrating one of his creations to Herbert Deutsch, co-inventor of the Moog synthesizer.

You have called yourself a “circuit manipulator / designer, artist, and professional Maker”—how do these things work together and influence one another?

That’s a fantastic question! I am a big preacher of the concept of “if you want to know more about it, then jump right into it and try it out”. In my experience it’s more difficult to learn from a chalkboard than by exploring / reading and practicing a new interest you are excited by. I am excited by technology and the power it gives me to express myself. As time has gone on since the early 80s, it has only gotten easier and easier to get involved with whatever evolving technology excited me at the time. Especially now with the Internet and all the fantastic resources available to learn from (YouTube, Instructables, kits and How-To websites, etc.), plus the constantly dropping prices on great development gear such as 3D printers and Arduino /RaspberryPi, it’s never been easier to learn about something new and get involved. I kind of saw this happening early on in the game, say about 1995 or so. This allowed me to really explore many different aspects of technology and art. More importantly it gave me the time needed to make it all fit together nicely as it does now. I started in graphic arts / web design and electronic music performance / production. I later would sell big name instruments for a couple of major retailers. I owned a marketing company which allowed me to hone in on even more technical skills such as video editing, text writing and promotion. In the end, every single part of that comes into play with my work in Dr. Blankenstein. To me, it’s proof that if you don’t know exactly what road will take you where you are going, any and every road you pick will take you there. You just need to be passionate about what you are doing.

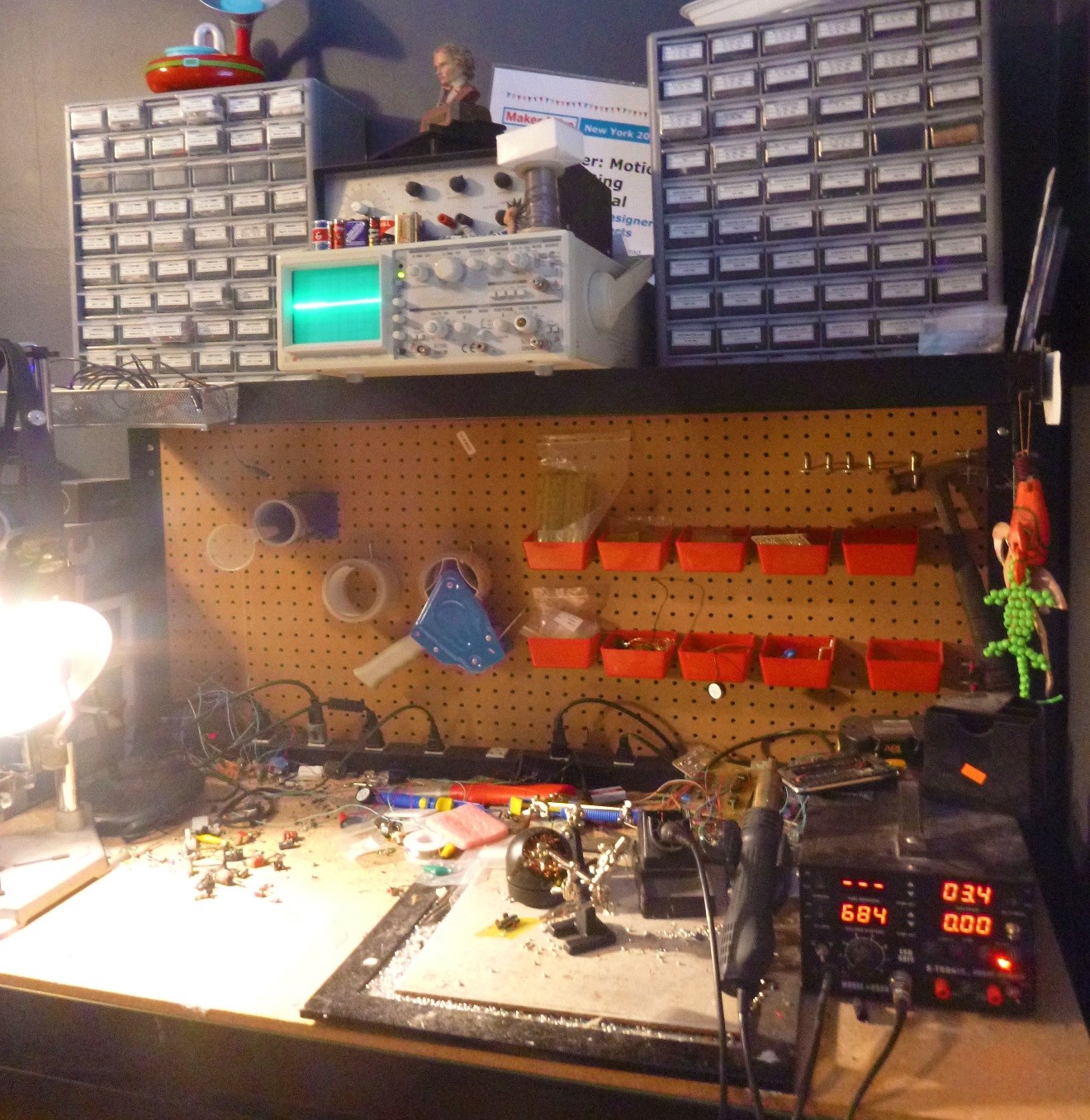

A view of Dr. Blankenstein’s workbench

Can you tell us a bit about your journey to learning the electronics end of things—things you learned that help you make/manipulate/creatively “break” the things that you do? Did you learn this formally at a school, or on your own by way of tinkering?

Well, it really started around 1986 or so when my father started doing HeathKits again. HeathKit was a company that started in the late 1940s and went out of business in the early 90s. Their basic idea was, “Why buy something at top dollar, when you can build it yourself for less?” It was a great way to learn about electronics and save some money on a gadget you wanted, but didn’t want to pay a lot for (some of their more popular / famous kits were the “HERO” robot used by Mr. Wizard and reportedly built by Steve Jobs in the early 1970s, a VHS Video Tape Recorder, or a color TV). My father was building the kits again (he was building a programmable analog musical doorbell kit), and he had built them as a child himself. Of course, I wanted in on the fun as well. My father would let me solder a resistor or two into place and explain the color coding system to me. He later would buy me an A.M. (not F.M, only A.M.) radio kit for me to complete myself, which I did (minus a few errors fixed by my father).

That was when my love for wanting to know what was inside machines grew, almost as much love for what the machine did itself was needing to know how it worked. At this point, I remember opening up many of my childhood toys to “see how they worked”. I was not always able to put them back together, but I ALWAYS managed to learn something in the process. This is a very important point to be made, one that I try to drive home in all of my workshops. It’s important if we as humans want to stay creative to make sure to look inside a machine and learn how it works. It connects you even deeper to all the hard work that went into making that device possible, develops a newfound respect for the world around you, and in the best case scenario (for what I do)… gets you excited to learn more about how things work and how to make something / or modify it yourself!

I’m a grassroots engineer, street taught… some would call me a hacker. It’s possible to be all of the above and more (it’s actually likely in many cases)! I am not saying that Engineering isn’t a wonderful thing to go to school for, and to follow as a career… it is and you should! I’m saying, you can be a Doctor, a Plumber or a Pizza maker and still be a fantastic Engineer. The most important part is the will / need to learn and the wonder to experiment and explore the world around and how it works.

A view of Dr. Blankenstein’s workbench.

Can you tell us about how you go about being a Maker in your day-to-day life? Do you have a workshop at home, or do you use any kind of organized Maker spaces?

I do have a shop in my Queens, New York apartment. It’s a tight space, but it’s rather amazing what can be done from it. One half is my computer workstation, and the other half is made up of two Maker workbenches. One bench I use mostly for circuitry which has my main soldering iron / rotary tool setup / oscilloscope / drill press etc. The other bench I use more for assembling my final products. So here you will find a lot of screw drivers, wrenches, extra screws / nuts and bolts etc. I try to keep the two areas separated so that my final pieces don’t accidentally get damaged by production tools (hot soldering irons, spinning drills) or metal scraps etc. I don’t use any organized Maker Spaces at this time, I wish there were more in my area. In New York, a lot of them seem to be in the Brooklyn area. Maybe I should start one for Queens!

Collaboration is a key attribute within the Maker community. Do you have a network of friends who are also involved in circuit bending or making sound-based work? Are there any online resources where someone might find such a community?

I wish I was working with more people than I am at the moment, because I do agree with you 100%. Collaboration is key to the Maker movement / community. That being said, it’s something easier said than done. As you get older, and you get more involved in your own work, it sometimes gets more difficult to find the time between your everyday work / life to make the connections one should be making when working on a lot different kinds of projects. I hate to sound like my parents here, but this is why SCHOOL is amazing and SO important. I can say to the younger Makers out there, as an adult… you will never have a better opportunity to connect and collaborate with great like minds than you will in middle / high school and college. So do what your parents say and take full advantage of it, you will thank us for it later. I do work with some other Makers out there from time to time, one of whom is Tim Sway… the amazing woodworker / instrument maker. We have collaborated on a few projects to date you can find out there if you search the web. There are a few other people I have been talking to lately that I hope to be working with in the near future as well. Lastly, that is why Maker Faire is such an amazing concept. All of us who work on our projects day after day, week after week, month after month, can finally come out in the daylight, meet follow Makers and show off ( and check out other people’s work) our hard work and collaborate.

Dr. Blankenstein’s “GoogaMooga”—his submission to the “Circuit Bending Challenge” at Moogfest 2012.

Can you talk about an especially challenging project, where the outcome was totally worth all of the effort you put in to it? Have you had any amazing accidental discoveries or spectacular failures?

It’s hard to talk about challenging projects and massive learning experiences without talking about the GoogaMooga (a 30min video of me building it can be found on my YouTube channel), my submission for the Moogfest 2012 “Circuit Bending Challenge” hacking contest. I had just gotten back into circuitry full time as was determined to be picked as part of the Top 3 to go to Asheville and compete. Did I have the skill level need to do so? Well, that was an entirely different story all together.

The idea was to use three 10 second voice recorders used to say Happy Holidays to Grandma and Grandpa in a custom greeting cards and turn them into an epic (contest winning) sampler / synthesizer. No problem, right!?! ;) Well I knew what I wanted to do, but the hard part was figuring out how to make it all work together. First I tried to etch a custom PCB mixer I planned on running all 3 sample units through. That was a total failure, a waste of sensitive time (the contest deadline was in days) and money. Plus, I had no idea how to run three separate 4.5volt samplers off one 9V power supply. The concept of a voltage divider chip / components hadn’t been revealed to me yet. So, I wound up running each of the mini voice sampler units off their own power supplies. Which pretty much meant loading the piece with NINE AA batteries and a 9V power supply to run the pile of LED lights I added and an FX section. Sounds crazy right? Later I would find out, even though I did just about everything completely wrong... I followed rule #1 in engineering, MAKE IT WORK! First and foremost, it must work… it may not look amazing on the inside, but make it work. In case you are wondering what rule #2 is, it’s always try to learn something new from your mistakes… I most certainly did as well. Guess what? I was picked to be part of the Top 3 of the contest and a relationship that still exists to this day was forged between Moogfest and myself. There isn’t much in life that will be easy or work perfectly when you first start doing it, just remember that everyone goes through it… and keep pushing through to your goals.

What is the benefit of making your own instruments, rather than exclusively playing commercially-purchased instruments? Are there any “quirks” to playing these types of things in front of an audience?

As for benefits, I suppose that depends on the artist who is using the instrument. I would guess the same can be said about “quirks” when performing with them. It really depends on the artist using it, how they are using it and what their final vision for their sound is. Meaning, an instrument can be built perfectly… in a way that it performs perfectly next to a commercially purchased instrument, but some would say, “Where’s the fun in that?” Some people look for pieces that are one-of-a-kind or unpredictable on purpose, it really depends on how the piece was built, and who is using it in what way. Playing a circuit bent piece live on the spot in front of a crowd, versus sampling cool sounds from it and using it in a computer written composition will get MUCH DIFFERENT results from the same exact instrument. I think someone who realizes that, will get the most out of a boutique instrument or something they built themselves.

Dr. Blankenstein is pictured above giving one of his custom guitar pedals to musician Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz of the Beastie Boys.

Do you think it is important for young people and new adult audiences to know about the “guts” of what powers everyday technology? What can we learn by taking things apart?

I think it’s beyond important. I’m a big believer that modern culture has people in the mode of “get the newest model” without really thinking about if their current model still does the trick for them. It seems to be a harmless habit to be in, but I don’t believe it’s harmless at all. Besides creating an amazing amount of exponentially growing yearly e-waste and wasting money… maybe even worse is that it makes us solely consumers. We need to be makers, innovators and thinkers… like the men and women whose devices / creations fill the halls of the Henry Ford Museum. Each one of them wanted to make it better than the last one, and with good reason… not just because they HAD TO have the newest model.

When we think about how things work, when we look inside and see what we can learn / recycle or reuse from it… or if nothing else take a look inside at all the hard work that goes into creating these devices. We gain respect for the item, we are amazed by it, we learn more from it… we are less impressed by the company who made it and if it’s the newest model and we are more impressed by what it does. We are impressed by what it does, and that we (the human race) have been able to make it happen in the last 80 years or so! We are amazing, we build amazing things!

What can people expect to learn at your Maker Faire workshop?

I love to show people how simple it is to get involved in circuitry! I like explaining to folks that with the knowledge of just a few easy to follow electronic principles, Circuit Bending very low cost battery powered electronics is actually rather easy, educational and rewarding (changing resistance to modify pitch, swapping out speakers for audio outputs, adding colorful LEDS, changing power sources etc.).

Most people have stuff laying around their house that would be thrown / given away that can easily be modified into one-of-a-kind Circuit Bent creations. The best part is, you have no choice but to get better and better at it and learn more about electronics as you go along. So, I hope to show folks some good examples of what that looks like when you are done with it, what it sounds like, and how they can get started to do the same thing at home (on a very small project budget).

Is there anything you are particularly excited to see at the museum?

There are so many things I am excited to see at the museum, in fact the entire concept of a museum like The Henry Ford excites me beyond belief. Talk about a museum that a Maker like me can really enjoy! Not that I don’t love my native fine art, science centers, or natural history museums here in New York, but a museum dedicated to invention, ingenuity and inspiration… that’s a place I can spend an entire week at. I will actually be staying a few days after the Maker Faire to make sure I don’t miss anything great. From what I see online, it’s just not possible to see the entire campus in 2 days (most certainly when the Maker Faire is going on).

What I am MOST EXCITED to see? It’s hard to have to pick, but I would have to say the communications and information technology artifacts in the museum. I just HAVE TO see the original Apple 1 computer and of course my friend Herb Deutsch’s original Moog Synthesizer prototype! I get goose bumps just typing that sentence. I’m excited to come see you Michigan—see you at the Detroit Maker Faire 2016!

by Kristen Gallerneaux, technology, music, Maker Faire Detroit

Image Courtesy of Moogfest.com

From May 18-22, Moogfest 2016—a festival dedicated to “the synthesis of music, art, and technology”—took place in Durham, North Carolina. While you may not have heard of Moogfest itself, you have almost certainly heard the sound of the synthesizer that is the namesake of the festival. If you’ve ever driven on the freeway nodding along to the Beatles “Here Comes the Sun,” or Kraftwerk’s “Autobahn,” you’ve heard the Moog. If you’ve rocked out to Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s “Lucky Man,” or danced to Blondie’s “Heart of Glass” or (keeping it local to Detroit) Parliament’s “Flash Light”—you know what the Moog sounds like. And if you grew up as a child of the 1980s, watching John Carpenter’s classic horror films—that soundtrack that punctuated the dread of Halloween? It was played on a Moog by Carpenter himself. My point is, the Moog has permeated our culture—its influence is everywhere, in plain earshot.

The Henry Ford is the repository for the original Moog prototype, pictured here. THF 156695

One of the reasons Moogfest is so important is because it raises awareness of the instrument’s impact. Not only is the Moog an essential innovation within the timeline of electronic instruments, it has also continued to influence the soundscapes of modern music. Another unique aspect of the festival is that its organizers give as much weight to organizing a carefully curated roster of lectures, workshops, and sound installations as they do in selecting the bands that play. From gatherings in small rooms where musicians lay their creative processes bare—to future-forward lectures about diverse topics like Afrofuturism, technoshamanism and radical radio—Moogfest’s speaker programming gives those interested in music, art, and technology the chance to be absorb new ideas about the history of technology.

This occasionally leads to interesting collisions and exchanges of ideas. Festival-goers might see a demonstration of IBM’s Watson project (a cognitive computing system), and later that day, hear Gary Numan play his groundbreaking 1979 Replicas album in its entirety. They might attend a workshop about “the internet of things,” and then take in a slice of a four-hour-long “durational performance” by analog synthesizer composer, Suzanne Ciani. Or for the truly committed—one might even participate in a “sleep concert” by Robert Rich, where the musician lulls participants to sleep with sound and influences their dreams from midnight until 8am the following morning.

Dave Tompkins, AUDINT, and Kristen Gallerneaux presenting their sonic research. The “mission patches” shown at center were discussed by AUDINT and represent cases in military history where sound was essential to the success of the mission: The Ghost Army, Operation Wandering Soul, and The Phantom Hailer.

While I have previously attended this festival as a spectator, this year I was honored to take part in Moogfest as an invited “Future Thought” speaker, where I helped to organize an event called Spatial Sound & Subhistories. The event opened with a presentation about some of The Henry Ford’s own sound and communications history artifacts—including the prototype Moog synthesizer. Writer Dave Tompkins gave a riveting talk about his book-in-progress, about the effect of the natural landscape on Miami Bass and hip-hop music. The event was capped off by a tour through “can’t believe this is real” sound history by the UK-based collective AUDINT, who began their discussion with the WWII-era “Ghost Army.”

Dorit Chrysler demonstrates the theremin in an adult workshop.

I also managed to take in a few events at the festival. On Thursday, I hit the ground running by participating in a theremin workshop led by world-renowned thereminist, Dorit Chrysler. Her resume is impressive, having played with the bands Blonde Redhead, Cluster, ADULT., Dinosaur Jr., and many others. Chrysler also founded KidCool Theremin School, which provides educational workshops to increase awareness of the instrument. After spending an enjoyable hour hearing stories about the theremin’s history and dipping my toes in the water of learning to play (but not too well), I’m very happy to say that KidCool Theremin School will be joining us at The Henry Ford for Maker Faire Detroit to offer a series of workshops and performances. Stay tuned for more details!

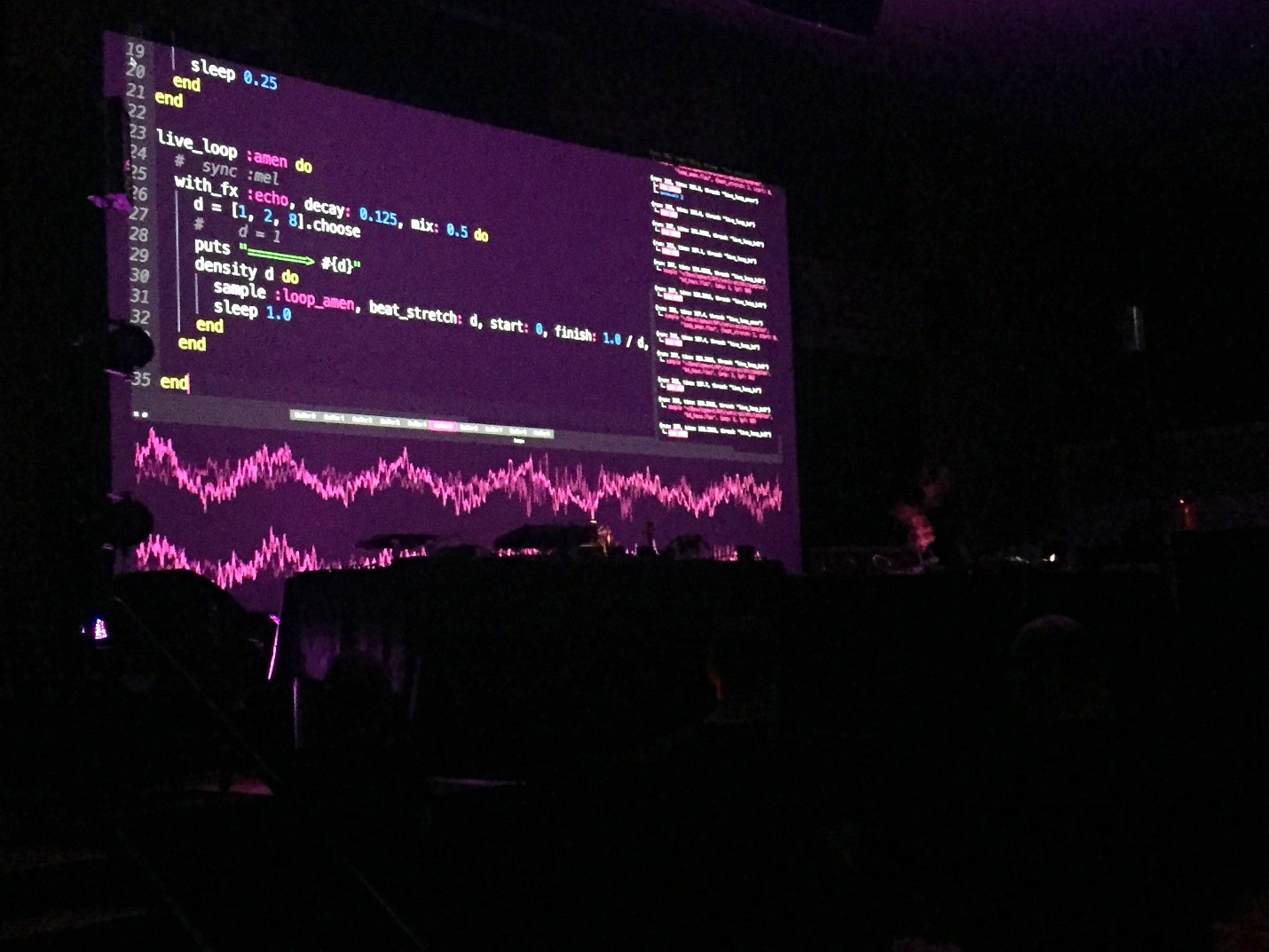

Sam Aaron makes electronic music using live Sonic-Pi coding.

The overlap between sound, art, and the technology used to make it has become indistinguishable in some cases. In this image, Sam Aaron is using Sonic Pi—a software program he created—to create live-coded synth music. As computer code swept quickly upwards on the projections behind the musician and the music changed with each command, it became obvious that Aaron was exposing the audience to the process he was using to manipulate sound. While my initial reaction was that this mode of music-making must be amazingly difficult, Sonic Pi was in fact developed as an entry point to teach basic coding in the classroom.

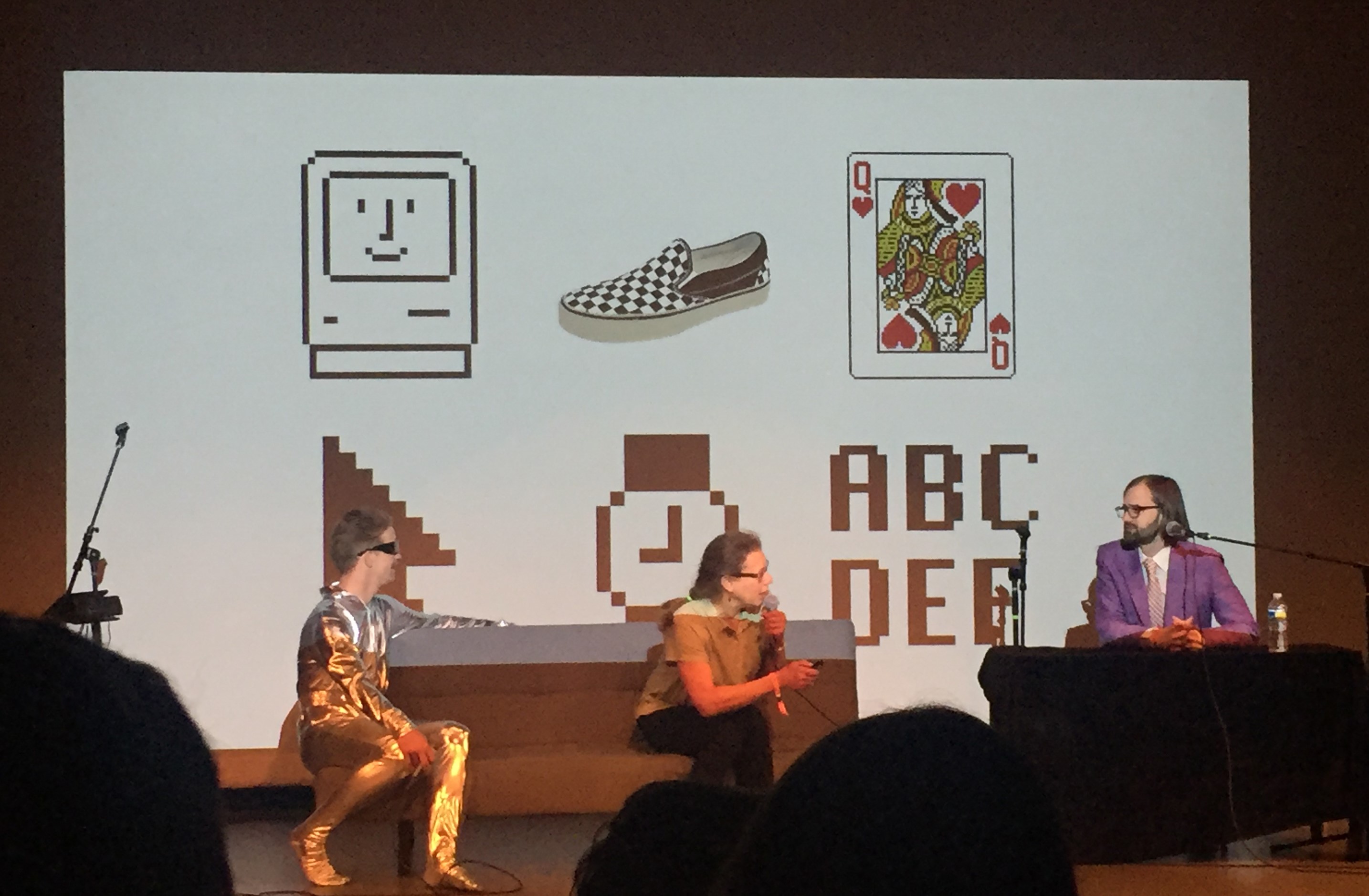

Ryan Germick talks about developing the Pegman icon for Google’s Street View.

At the “Arts & Smarts” event, Google Doodle team leader Ryan Germick played host to something that fell somewhere between a stand-up comedy and technology talk show—complete with a “robot” named “Jon Bot” (actually Germick’s brother in a silver space-age suit). Through a stream of constant self-effacement and hilarious jokes, Germick talked about the origins of the icons he created during his career at Google. As the artist behind the Google Maps “Pegman” icon in Street View, Germick now leads the team responsible for over 4000 Google Doodles—including an accurate version of a Moog synthesizer in celebration of inventor Bob Moog’s birthday.

Susan Kare talks about her career designing digital icons.

Keeping with the talk show format, Germick also interviewed a few other guests. Susan Kare, an artist and graphic designer responsible for “creating every icon you’ve ever loved” gave a retrospective tour through her career as a pioneer of pixel art and digital icons. While working at Apple, she created the “Chicago” and “Geneva” typefaces, as well as the “sad” and “happy” Mac graphics—and the Command key on Apple keyboards.

Virtual Reality designer Manuel Clément has worked on many projects at Google, including the self-driving car project.

Next, Manuel Clément, Senior Virtual Reality Designer at Google, spoke about his early life in computing and his work on platforms like Flash in the 1990s, Google Chrome, Doodles, a Self-Driving car program, and Cardboard. Clément showed the outcome of a new prototyping team called Google Daydream, who are testing issues of social interaction, motion, and scale in virtual reality. He reminded the audience that VR is about “experiencing the impossible,” yet he is aware of its current limitations. In reference to an intense bout of app experiments, Clément asked: “What is VR good for? Maybe it’s good for nothing. But how about we build 60 things over 30 weeks and figure it out?”

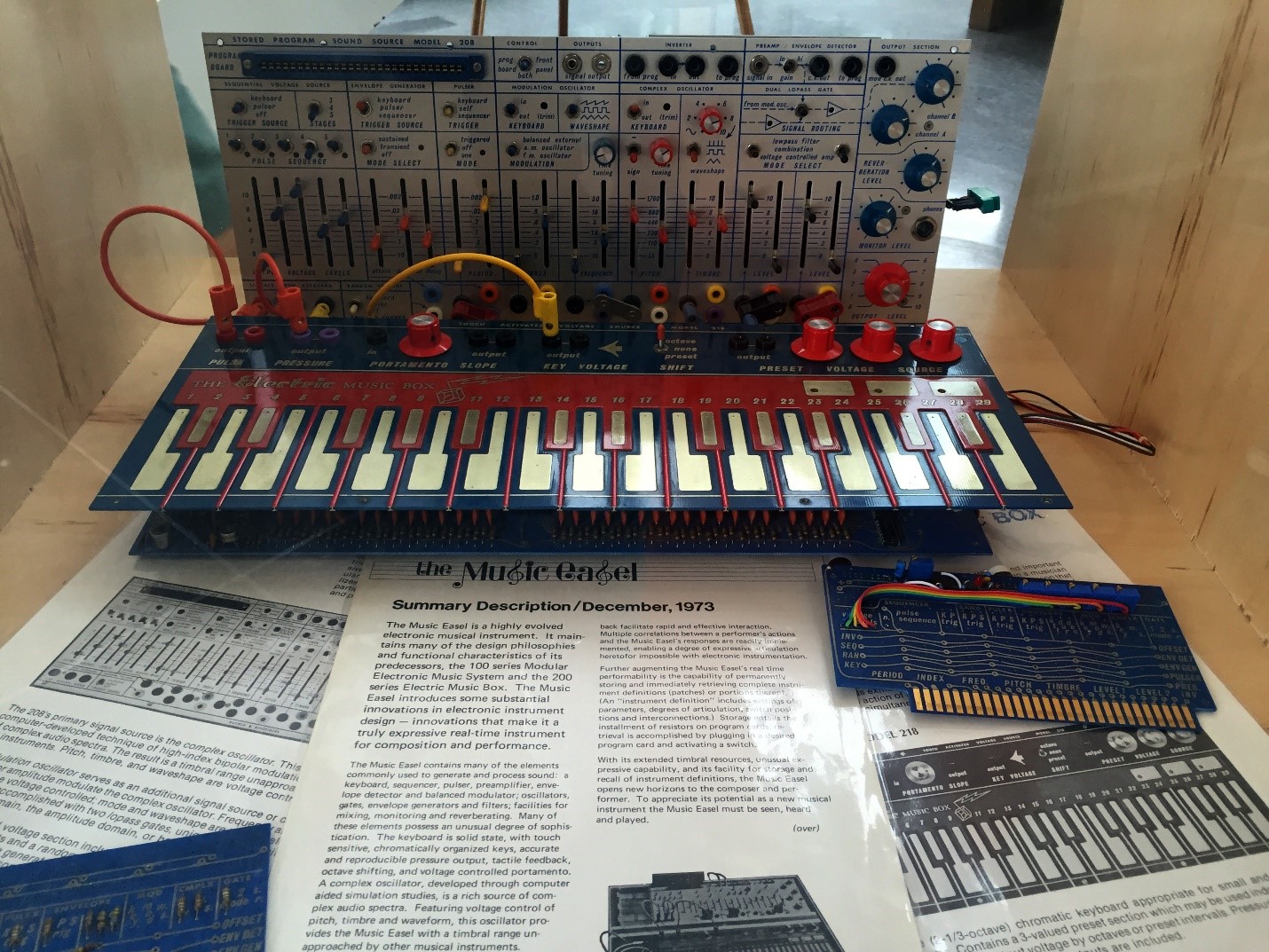

An exhibit celebrating the legacy of another early synthesizer pioneer, Don Buchla.

A collection of Don Buchla instruments and memorabilia was also on view at Moogfest. Buchla, who is located in Berkeley, California, began creating analog and touch-sensitive synthesizers at about the same time as Bob Moog was creating his synthesizer prototype on the East Coast. The exhibit was created from the collection of Richard Smith—an important instrument technician in his own right, and one-time apprentice of Buchla. Smith provided a glimpse into one of the most complete collections of Buchla material ever assembled—this small portion of his archive certainly left me wanting to see the rest!

A “Minimoog Model D” synthesizer under construction at the Moog Music Pop-Up Factory.

Moog Music, whose headquarters and factory are located in Asheville, NC, built a “pop-up factory” for the Durham’s Moogfest. Even on the last day of the festival, the enthusiasm in the building was positively electric. Every demonstration synthesizer available was being played by a visitor, and displays related to Moog’s history were being used as photo opportunities: fans posed for photos next to a larger-than-life image of composer Wendy Carlos and by the circuit boards that once powered the synths of Kraftwerk, Dr. Dre, and Bernie Worrell (who to the delight of fans, dropped in for an impromptu session at the Factory).

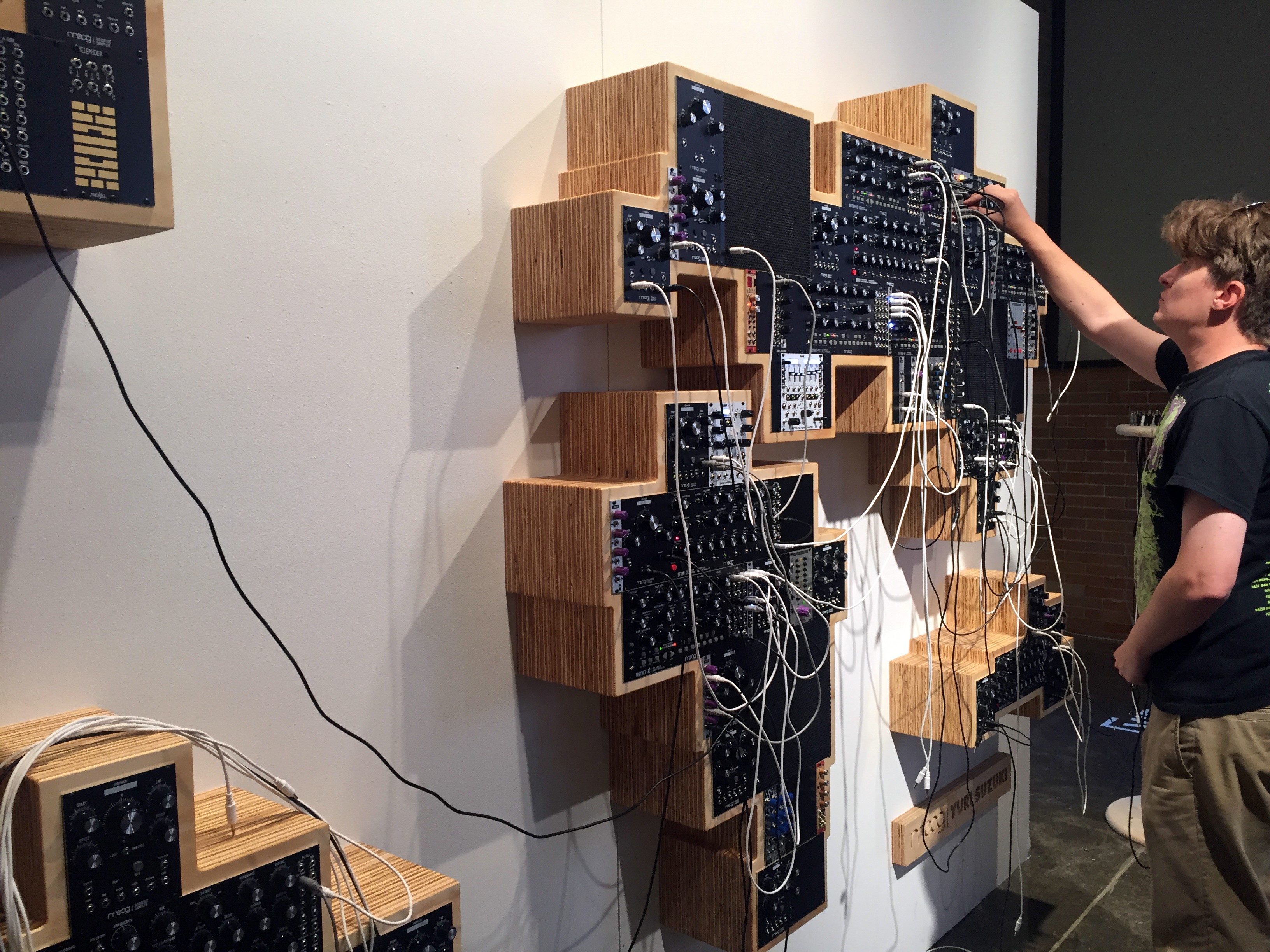

A view of Yuri Suzuki’s interactive Global Synthesizer Project.

In the spirit of encouraging a Maker Culture, the three finalists of Moog’s 5th Annual Circuit Bending Challenge were on display—a contest that asks contestants to create a unique electronic instrument for $70 or less. One wall was taken up by a collection of analog synthesizers in the shape of a world map. Designed by sound-art designer Yuri Suzuki, the Global Synthesizer Project asked people to contribute audio recordings of their regions. When the project debuted at Moogfest, visitors were allowed to interact by creating wire “patches” to play the gigantic archive of international sound.

The Minimoog Model D, exploded and assembled.

Moog Music also used the buzz around the festival to announce the revival of one of their most iconic synthesizers—the Minimoog Model D. Using a remarkable amount of research, craftsmanship, and detail-oriented production, the company is staying true to the original 1970 version, down to the last circuit. Visitors could see an “exploded” Minimoog, and step over to the factory stations, where the various stages of their assembly was explained.

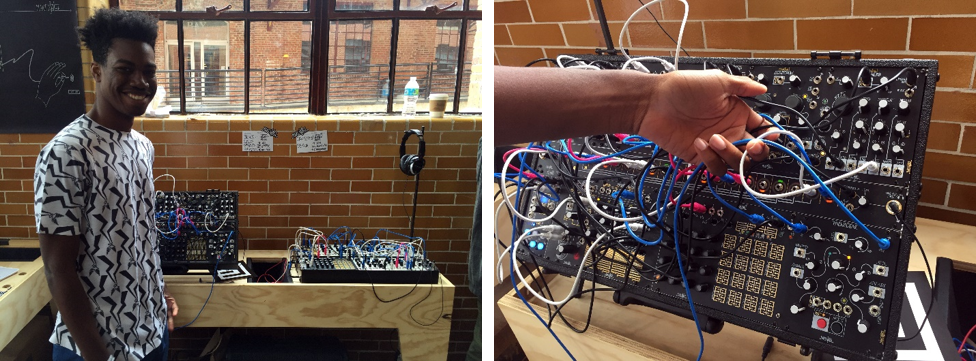

Darion Bradley of Make Noise shows off a modular synthesizer system.

Darion Bradley of Make Noise shows off a modular synthesizer system.

Moogfest, out of necessity and the modern spirit of music-making, isn’t all Moog all the time. In fact, there is a general spirit of comradery and democracy that permeates the event. In the Modular Marketplace, modern-day instrument makers show off their capabilities. In particular, small companies who create Eurorack modules—a sort of synthesizer that you can build piece-by-piece, by chaining together components—have a strong presence at Moogfest. Companies like Synthrotek, Mutable Instruments, Bleep Labs (along with dozens of others) demonstrated their gear and allowed people to try it out. The philosophies of innovation behind the Asheville-based Make Noise company seemed particularly relevant—not only with regard to their own instruments—but also to the general values found among creative technologists at this particular moment in time: “We see our instruments as a collaboration with musicians who create once in a lifetime performances that push boundaries and play the notes between the notes to discover the unfound sounds. We want our instruments to be an experience, one that will require us to change our trajectories and thereby impact the way we understand and imagine sound.”

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communications and Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

computers, popular culture, by Kristen Gallerneaux, events, technology, musical instruments, music

On April 16-17, 2016, the 4th USA Science & Engineering Festival was held in Washington, DC. This national event is the largest science festival in the country, with over 3000 exhibitors, a speaker program, and hundreds of hands-on activities for attendees to participate in. Free admission helps the festival to draw an annual attendance of over 350,000 visitors, which range from school groups and educators—to curious adults (and at least one tech-obsessed curator). Much like The Henry Ford’s own Maker Faire Detroit, the exhibits buzzed with possibility and discovery for all things technological and experimental. The enthusiasm in the exhibit halls was contagious among young and adult audiences alike, as mixture of independent startups, educational collectives, government organizations, and commercial investors collided under one roof, under one common goal: to engage young audiences by providing formative and positive interactions with the STEM fields—and to suggest the future possibilities of the weight of technology within our everyday lives. Here are a few favorite moments from the festival.

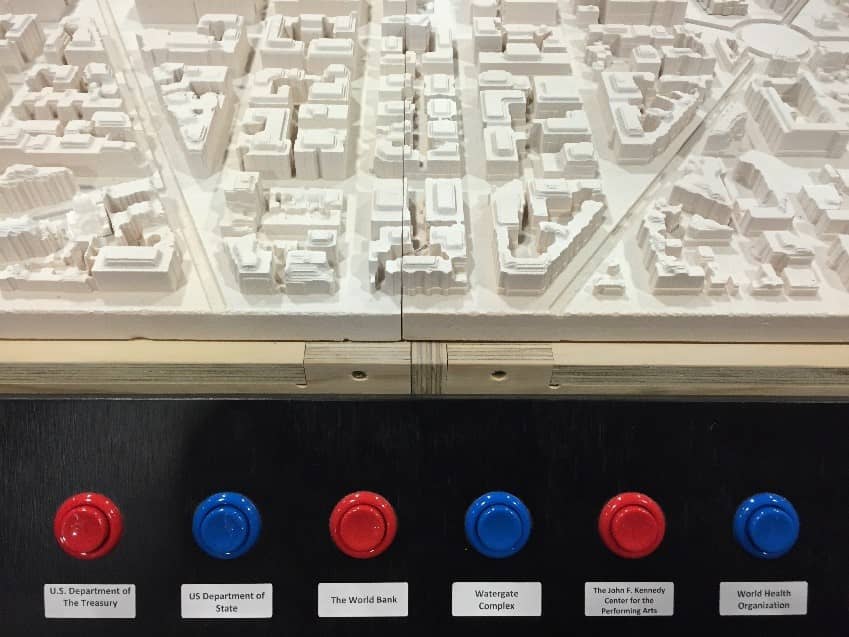

SketchUp, a computer program for 3D modeling, showed a multi-dimensional range of abilities with projects that fell into the entertainment-based arena (a DIY foosball table or mechanical dinosaur)—to more educational applications such as an interactive, light-up plan of Washington, DC. Thanks to SketchUp’s open source model, with access to a 3D printer, you could theoretically create your own model of the city of Detroit or even of The Henry Ford museum by using ready-made SketchUp plans, available for free online. As SketchUp’s demonstrators noted, once the models are printed and a simple LED-light structure is put into place, these models “can be great for learning about an existing area of the world, re-imagining one, or coming up with your own world altogether.”

The robotics company, Festo, was onsite to demonstrate examples of their beautiful and uncanny biomimetic designs. A tank full of their AquaJelly devices perfectly mimed the swarming behavior of real-world jellyfish. Similarly, the company has created autonomous “AirPenguins,” butterflies, and bionical ants that “collaborate” through machine-based learning processes. While the visual presence of swimming robotic jellyfish is hypnotic to be sure, the company’s goals go much deeper than pure flash and fodder. Festo’s mission is to improve modern manufacturing by recreating the patterns of collaboration, control, and innovation already found within the wonders and orders of nature.

The National Security Agency and National Cryptologic Museum were also present. A hands-on display allowed guests to press keys on a working Enigma machine, well-known for its role in WWII-era communication. Machines like this were famously used by the German military to encrypt messages, while the secretive work happening at Bletchley Park in England was working to crack the Enigma’s codes. Activities at the NSA’s booth introduced young audiences to the historical world of cryptology and codebreaking via cipher disks, but also demonstrated how the same concepts could be used in contemporary cybersecurity. The Agency not only showed youth how to create a strong password, but also provided “cybersmart” awareness training in the privacy and use of social media.

Several large pavilions encouraging careers in space science and education formed an undeniably strong presence at the festival. NASA, Lockheed-Martin, and a few others created welcoming zones jam-packed with hands-on activities. At the NASA exhibit, younger audiences could rub shoulders with working NASA scientists, see models of Mars rovers, learn about modern-day space exploration, and a glimpse into the scientific principles behind it all. Lockheed-Martin’s pavilion was taken over with a speculative display of Mars-related technology—although, as the banners posted throughout the experience cleverly reminded visitors: “This Science Isn’t Fiction.” As I stared, admittedly mystified, at the impressively fast and fluid industrial 3D printer in front of me (that seemed a bit like it had jumped straight out of a sci-fi movie about sentient technology), a Lockheed-Martin expert patiently explained the process unfolding before us. While the MRAC (Multi-Robotic Additive Cluster), was set up to print with plastic at the festival, this machine is primarily used to print flight-ready parts for satellites with titanium, aluminum, and Inconel. It can produce rapid-fire prototypes, but also polished parts, cutting the time to, for example, create a satellite fuel tank from 18 months—down to 2 weeks. Lockheed-Martin has worked closely with NASA on every mission flown to Mars, pooling knowledge and manufacturing resources on aspects of orbiters, landers, and rovers. As the expert on hand explained, “we have to collaborate—no one can do everything, all by themselves.”

As part of the Saturday speaker series, NASA astronaut Jeff Williams was livestreamed from the International Space Station onto the festival’s stage. Young audience members were given the opportunity to ask him questions like “What does it smell like in space?” and “What happens to your body when you live in space?” Life in space is something that Williams knows well, having spent 534 cumulative days in space. And as it turns out, Williams, space travel, and the modern media age are old friends—in 2009, he formed part of the first NASA team to hold a live Twitter event in space.

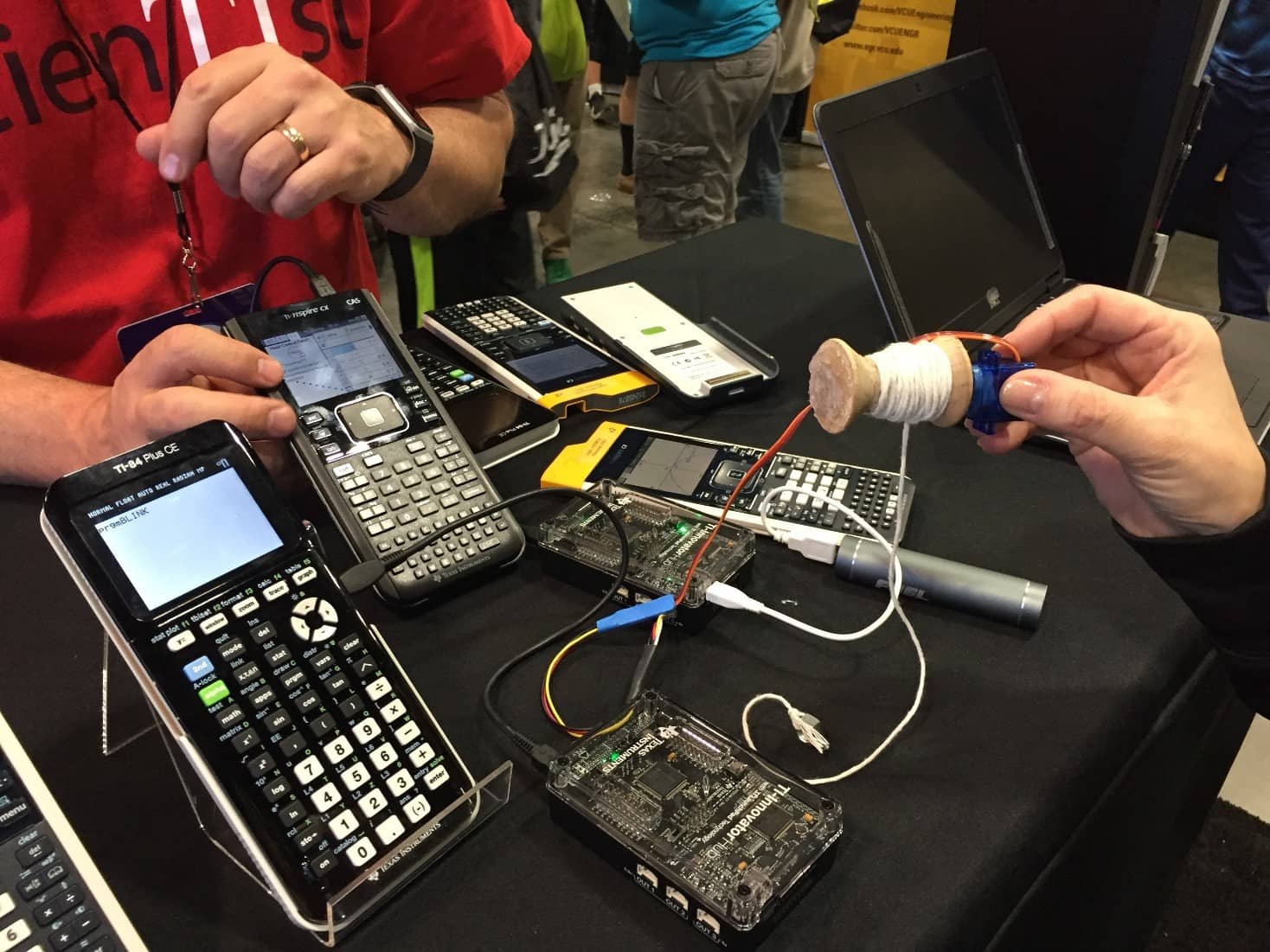

Giants of calculator history, Texas Instruments, demonstrated a new line of STEM-friendly educational calculators. Their new TI-Innovator System allows students to learn the basics of computer coding (in BASIC language, no less) on their calculators, building skills bit-by-bit in a series of “10 Minutes of Code” lesson plans. Sympathetic to the idea that STEM concepts are best enacted in some kind of physical reality, beyond the calculator’s screen, the company has created the TI-Innovator Hub (the clear box depicted lower center). The Hub, linked up to a calculator, can activate a variety of functions: LED lights, speakers, optical sensors, and ports that allow it to communicate with external breadboards, computers, and other controllers. In this image, the Hub has been programmed to raise and lower a spool of string, meant to mimic the mathematical problem of how low to lower a fishing boat anchor.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

by Kristen Gallerneaux, space, technology, education, events

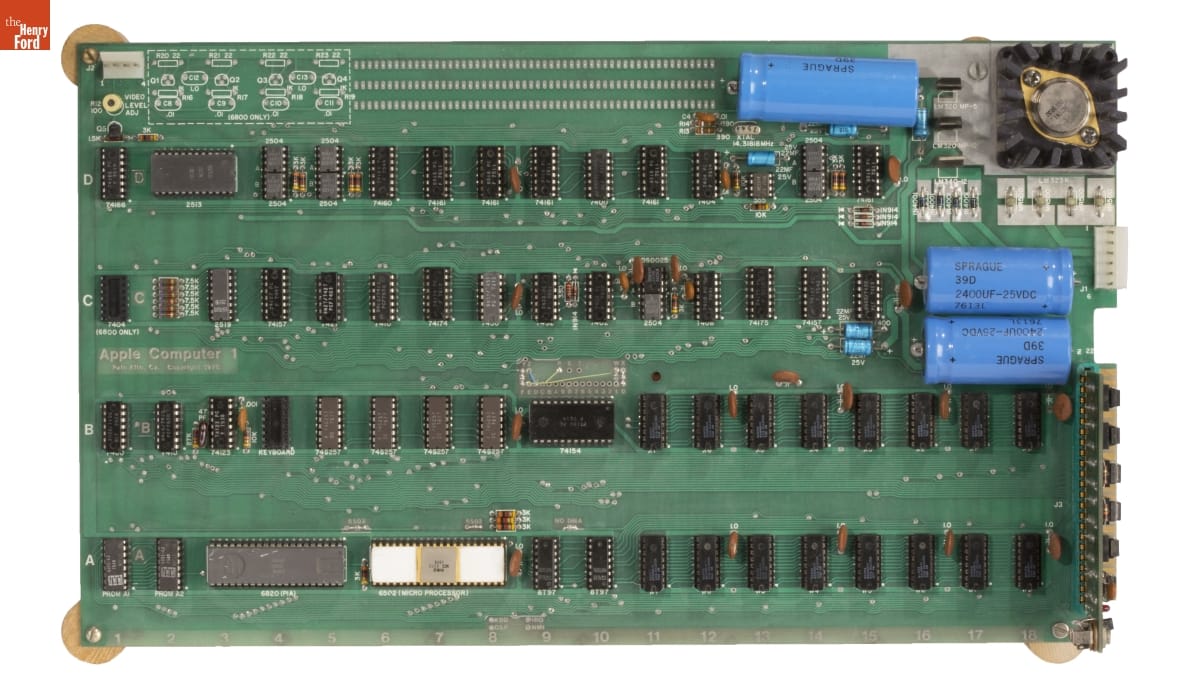

Apple 1, 40 Years Later

On April 11th, 1976—40 years ago—the first Apple product made its public debut. The origins of this device began the previous year, on a rainy day in March of 1975, when a group of enthusiastic computer hobbyists met in a garage in Menlo Park, California. Steve Wozniak attended this inaugural meeting of the Homebrew Computer Club, and walked away with the inspiration to create a new breed of computer. This was the beginning of the Apple 1 computer.

Today, thanks to the combined technical knowledge and passion of Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs, we can celebrate the anniversary of a milestone. For a limited time, The Henry Ford’s Apple 1 computer will be on display in the museum’s William Clay Ford Plaza of Innovation, April 11-30, 2016. We hope you’ll join us in celebrating the legacy of this key artifact of the digital age.

A few facts and numbers to consider:

- Apple Computer, Inc. was founded on April Fool’s Day: April 1, 1976.

- On naming the business, Steve Jobs said: “Apple took the edge off the word ‘computer.’ Plus, it would get us ahead of Atari in the phone book.”

- This Apple 1 is one of the first 50 ever made, sold directly through the early computer retailer, The Byte Shop.

Paul Terrell, owner of The Byte Shop, saw Wozniak’s demonstration of the Apple 1 at a Homebrew Club meeting, and placed the first wholesale order.

When you purchased an Apple 1, you were purchasing the motherboard.

Peripherals like a keyboard, monitor, power supply, tape drive were bought separately.

Approximately 200 Apple 1’s were sold in total; the location of approximately 46 of these original units is known today.

Only 9 of the original batch of 50 Apple 1’s are documented as being in working condition.

The Henry Ford’s Apple 1 is completely unmodified, with all of its original chips. It is fully operational.

Do you want to know more about the Apple 1? We at The Henry Ford have been happy to show off this incredible artifact at every given opportunity. You can read the original blog post announcing its acquisition, or an in-depth article that asks the question: “What if everyone could have a personal computer?” You can see detailed photographs or watch a video describing the experience of winning the computer at auction, or witness a very happy gathering of staff members unpacking it upon its arrival. You can also watch a video of Mo Rocca and our Curator of Communications and Information Technology, Kristen Gallerneaux, talk about the power (and limitations) of early computers in an Innovation Nation episode. And if you need more yet, you could watch a new Connect3 video about the surprising connections that exist between the Apple 1 and other artifacts in our collection, or even still, dive deep into the mind of Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak in an extensive OnInnovation oral history.

Kristen Gallerneaux is Curator of Communication & Information Technology at The Henry Ford.

California, 1970s, 20th century, technology, computers, by Kristen Gallerneaux

Report from the Field: World Maker Faire 2015

Over the weekend of September 26-27, 2015, the 6th annual World Maker Faire was hosted at the New York Hall of Science. Much like Maker Faire Detroit at The Henry Ford, New York’s Faire benefited from an added sense of shared history that comes from producing such an event on the grounds of a museum. Maker demonstrations, workshops, and displays were set up outdoors, on the former grounds of the 1964 World’s Fair—an event that was full of technological spectacle. And inside the Hall of Science, modern-day Makers found communal space alongside the museum’s interactive demonstrations about space exploration, biology, mathematics, and much more. The continuum of the importance of the technology of the past—in tandem with the anticipative futures of the Maker Movement—was substantial and exciting to witness. Continue Reading

music, technology, computers, radio, video games, events, by Kristen Gallerneaux, making

Light and Static: The Origins of the Xerox Copy

A date, and a place, written by hand: 10.-22.-38. Centered underneath: Astoria. The letters are composed of bold strokes, defined at the edges and flaking towards the center. The whole arrangement seems to be crumbling towards the bottom of the page, like it is made of dust that could be wiped away by the backstroke brush of a hand. Its purpose uncertain, this is not a “note to self” to be in a place, on a certain date—this is the first successful Xerox copy ever made.

A date, and a place, written by hand: 10.-22.-38. Centered underneath: Astoria. The letters are composed of bold strokes, defined at the edges and flaking towards the center. The whole arrangement seems to be crumbling towards the bottom of the page, like it is made of dust that could be wiped away by the backstroke brush of a hand. Its purpose uncertain, this is not a “note to self” to be in a place, on a certain date—this is the first successful Xerox copy ever made.

The inventor of the modern photocopier, Chester Carlson, began thinking about mechanical reproduction and the graphic arts at a young age. His first publishing effort was a newspaper called This and That, circulated among family members when he was ten years old. The first edition was handwritten, with later issues composed on a Simplex typewriter given to him as a Christmas present in 1916. In high school, Carlson was forced to work multiple jobs in order to support his impoverished and ill family; one of these jobs found him sweeping floors at a printing shop. Working around printing machinery inspired him to publish a science journal, but the tedium of setting type by hand, line by line, led him to give up on this idea quickly. The machines did not support the quickness of his mind. It was in these frustrations with printing equipment—the fussiness of equipment that reproduced documents during his youth—that motivated Carlson to create the instantaneous printing process that would eventually be central to the creation of the Xerox photocopier. Continue Reading

technology, by Kristen Gallerneaux, communication, IMLS grant

Mothership: The Making of an Urban Maker

At Maker Faire Detroit 2015, the “Mothership” will descend into The Henry Ford Museum. Created by the Detroit collaborative group, ONE Mile, the Mothership looks like a lunar lander, acts as a mobile DJ booth—but is also so much more. Kristen Gallerneaux, our Curator of Communications and Information Technology, caught up with the group to ask them a few questions about their project.

Can you explain what the Mothership is?

The Mothership is a Parliament-Funkadelic inspired mobile DJ booth, broadcast module, and urban marker designed to transmit cultural activity from Detroit’s epic North End. Channeling Ancient African material culture and Afrofuturist aesthetics, the deployable pod energizes underused sites, creates a sense of place, and helps signal that Detroit’s creative prowess is powerful and uninterrupted. But most simply it’s an object, one that people can identify with. Stationed without programming, it’s a mini-monument. Ajar and pulsating with music, it reveals a DJ and accompanies a broad spectrum of public events, performances, and community gatherings. Add smoke machines and colored lighting, and the Mothership creates the impression of having “just landed”. Continue Reading

design, music, Michigan, Detroit, Maker Faire Detroit, making, by Kristen Gallerneaux