Posts Tagged by matt anderson

Ford’s Five-Dollar Day

On January 5, 1914, Henry Ford and his vice president James Couzens stunned the world when they revealed that Ford Motor Company would double its workers’ wages to five dollars a day. This groundbreaking decision for the average Ford assembly line worker salary generated glowing newspaper headlines and editorials around the world. The notion of a wealthy industrialist sharing profits with workers on such a scale was unprecedented.

In the century since, many theories have been posited for Ford’s bold move. Some suggested the increase was to justify assembly line speed-ups. Others speculated it was to counteract high labor turnover due to increasingly monotonous assembly line work. Ford admirers believed it was pure philanthropy and a progressive step towards improving Henry Ford's workers' rights. Cynics asserted that it was little more than an elaborate publicity stunt. As usual, the truth lay somewhere in the middle.

More Monotony, But More Money

To a large degree, Ford’s implementation of the Five-Dollar Day cannot be appreciated without first understanding his advances with the moving assembly line. Experiments through 1913 and into 1914 reduced the time required to build a Model T automobile from 12½ hours to a mere 93 minutes. Increased efficiencies lowered production costs, which lowered customer prices, which increased demand. The public was eager to buy all of the cars Ford could build.

Explosive production gains came at the cost of worker satisfaction. The very goal of the moving assembly line was to take what had been relatively skilled craftwork and reduce it to simple, rote tasks. Workers who had taken pride in their labor were quickly bored by the more mundane assembly process. Some took to lateness and absenteeism. Many simply quit, and Ford found itself with a crippling labor turnover rate of 370 percent. The assembly line depended on a steady crew of employees to staff it, and training replacements was expensive. Ford reasoned that a bigger paycheck might make the factory’s tedium more tolerable.

If the need to retain workers was a partial motivation for the Five-Dollar Day, then the solution may have worked too well. Within days of the announcement, thousands of applicants came to Detroit from all over the Midwest and entrenched themselves at the Ford’s gate. The company was overwhelmed, riots broke out, and the crowds were turned away with fire hoses in the icy January weather. Ford announced that it would only hire workers who had lived in Detroit for at least six months, and the situation slowly came under control.

Strings Attached

Those who secured jobs at Ford soon discovered that the generous Ford worker salary came with conditions. Lost in the headlines was the fact that the pay increase was not a raise per se, it was a profit sharing plan. If you made $2.30 a day under the old pay schedule, for example, you still made that wage under the Five-Dollar plan. But if you met all of the company’s requirements, Ford gave you a bonus of $2.70.

Part of Henry Ford’s reasoning behind the Five-Dollar Day was that workers who were troubled by money problems at home would be distracted on the job. If higher pay was intended to eliminate these problems, then Ford would make sure that his employees were using his largesse “properly.” The company established a Sociological Department to monitor its employees’ habits beyond the workplace.

To qualify for the pay increase, workers had to abstain from alcohol, not physically abuse their families, not take in boarders, keep their homes clean, and contribute regularly to a savings account. Moral righteousness and prudent saving were all well and good, but they were not generally an employer’s business—at least not outside of working hours. In contrast, Ford Motor Company inspectors came to workers’ homes, asked probing questions, and observed general living conditions. If “violations” were discovered, the inspectors offered advice and pointed the families to resources offered through the company. Not until these problems were corrected did the employee receive his full bonus.

Modifying manufacturing methods was one thing. Modifying the people who carried out those methods was quite another. Henry Ford and his supporters may well have seen the Sociological Department as a benevolent tool to benefit his employees, but the workers came to resent the intrusion into their personal lives. Ford himself eventually realized that the Sociological Department was unsustainable. By 1921, it was largely dissolved.

Wages Up, Sales Up

As for charges that Ford raised pay in pursuit of publicity, there’s no question that the Five-Dollar Day brought a spotlight on Ford Motor Company. But publicity is fleeting, and the Five-Dollar Day’s impact was far greater than newspaper headlines. Other automakers soon boosted their own wages to keep pace with Ford. Automobile parts suppliers followed suit. In time, workers in any number of fields were earning genuine “living wages” that afforded them comfort and security above basic food, shelter and clothing needs.

It’s no small detail that, as Henry Ford slyly observed, in the course of improving his employees’ standard of living, Ford also created a new pool of customers for his Model T. The Five-Dollar Day helped to bring members of America’s working class into its middle class. Better wages, combined with the affordable goods produced by the assembly line, are cornerstones of the prosperity that has characterized American life for so many of the past 100 years.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation of The Henry Ford.

20th century, 1910s, Michigan, manufacturing, labor relations, Henry Ford, Ford workers, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, by Matt Anderson

The Stingray Returns!

Just when you thought it was safe to go back into the water… er, dealership… Chevrolet’s iconic Corvette Stingray* is back. The seventh-generation Corvette just received Automobile Magazine’s “Automobile of the Year” award. It’s a great honor, and it affirms the car’s right to wear the hallowed “Stingray” name – not seen on a Corvette since 1976.

Given Corvette’s long-established status as America’s sports car, it’s easy to forget that the first models lacked a performance image. The 1953-54 cars featured inline six engines and two-speed automatic transmissions – not exactly scream machines. That began to change with the 1955 model year when a V-8 and a three-speed manual shift became options. Production figures climbed steadily thereafter, but the Corvette arguably didn’t come into its own until the 1963 model year when General Motors styling head Bill Mitchell shepherded the magnificent Sting Ray into production.

Mitchell’s car was a radical departure from previous Corvettes. The gentle curves of the earlier cars (readily seen on The Henry Ford’s 1955 example) were replaced with sharp edges. The toothy grille gave way to an aggressive nose with hidden headlights, and the roof transitioned into a racy fastback. The car was a smash in its day and continues to be perhaps the most desirable body style among collectors.

The 1963 Sting Ray was inspired by two of Mitchell’s personal project cars. The 1959 Stingray Special was built on the chassis of the 1957 Corvette SS race car. When American auto manufacturers officially ended their racing programs in the summer of 1957, the SS became surplus. Mitchell acquired the car, rebuilt it into a racer, and sidestepped the racing ban by sponsoring the car personally. The rebuilt Stingray Special’s unique front fenders, with bumps to accommodate the wheels, became a prominent part of the 1963 production car.

The second inspiration was the Mako Shark concept car introduced in 1961. While fishing in Bahamas that year, Mitchell caught an actual mako shark which he mounted and displayed in his office. The shark’s streamlined body and angular snout, combined with elements from the Stingray race car, produced a show car that turned heads wherever it was displayed.

Fifty years later, some believe that the mid-1960s Sting Rays are still the Corvette’s styling peak. Clearly, the 2014 model had much to live up to if it was to carry the Stingray name. The honors from Automobile Magazine suggest that the latest Corvette is worthy indeed.

UPDATE 01/13/14: The 2014 Corvette Stingray just took top honors as "North American Car of the Year" at the North American International Auto Show. It's further proof that the car has earned its legendary name!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford

* Stingray nomenclature is a confusing business. Bill Mitchell’s 1959 race car was “Stingray” – one word. The 1963-1967 production cars were “Sting Ray” – two words. The 1968-1976 and 2014 cars reverted to “Stingray.” For what it’s worth, the fish itself is “stingray.”

20th century, 1960s, 1950s, 21st century, 2010s, race cars, nature, design, Chevrolet, cars, by Matt Anderson

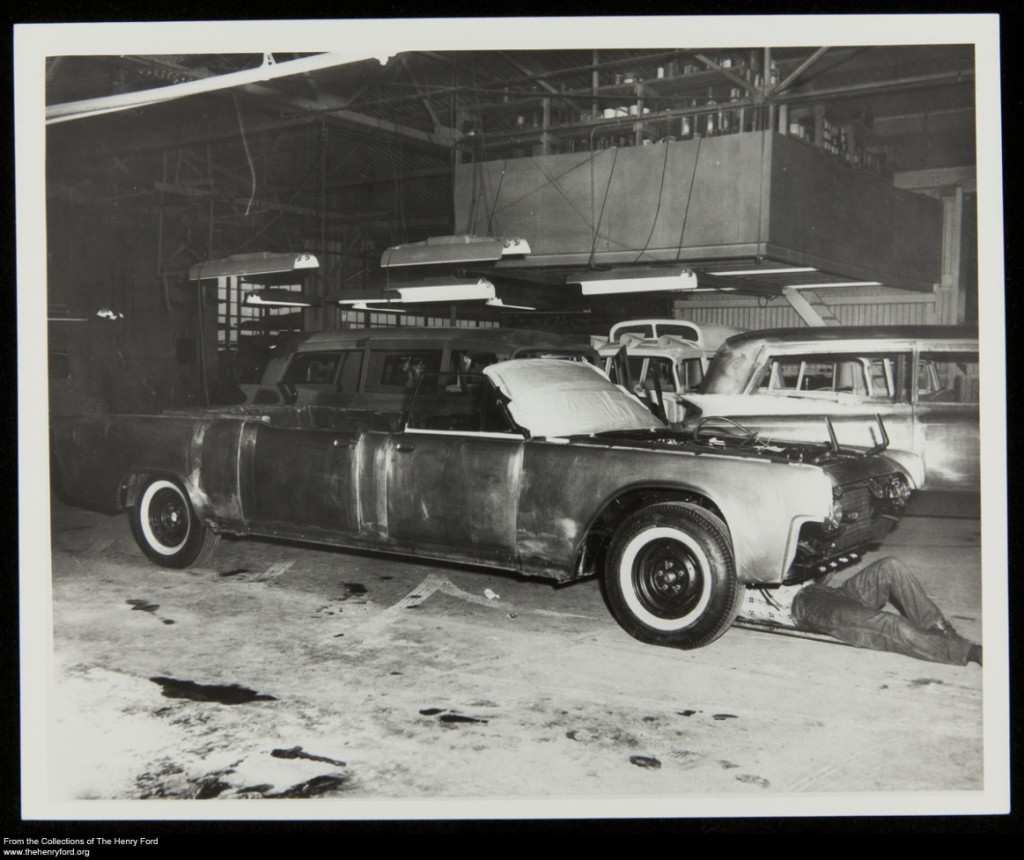

JFK Remembered: The X-100

The X-100 pulls away from the White House, February 1963. / THF208724

November marks the anniversary of one of the most dramatic – and traumatic – turning points in American history: the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963. In that single instant, the perceived calm of the postwar era was shattered and “The Sixties” – civil rights legislation, Vietnam, the counterculture – began. Few artifacts from that day are as burned into public memory as the 1961 Lincoln Continental that carried President Kennedy through Dallas.

The car, code named X-100, started life as a stock Lincoln convertible at Ford Motor Company’s Wixom, Michigan, assembly plant. Hess & Eisenhardt, of Cincinnati, Ohio, stretched the car by 3½ feet and added steps for Secret Service agents, a siren, flashing lights and other accessories. Removable clear plastic roof panels protected the president from inclement weather while maintaining his visibility. The car was not armored, and the roof panels were not bulletproof. The modified limo cost nearly $200,000 (the equivalent of $1.5 million today), but Ford leased it to the White House for a nominal $500 a year.

Continue Reading

by Matt Anderson, cars, Ford Motor Company, presidential vehicles, presidents, limousines, JFK

On Self-Driving Cars: Revolution or Evolution

I’m keenly interested in the move toward self-driving cars, so an article in USA Today caught my eye last week: “Self-driving cars? They’re (sort of) already here.” As the headline suggests – apart from the parenthetical hedge – the autonomous auto isn’t a far-off fantasy anymore. The odds are that some of us will be playing Michael Knight before the end of the decade.

While it’s easy to get wrapped up in the exciting things Google is doing with its fleet of autonomous Prii, just as earlier generations were wowed by Norman Bell Geddes vision of automatic cars in his Futurama at the 1939 World’s Fair, it seems that self-driving cars aren’t going to arrive in a technological flash. Rather, they’ve been sneaking up on us bit by bit for a century.

One might trace their development all the way back to Charles Kettering’s electric starter on the 1912 Cadillac. Sure you had to flip the switch, but that car cranked itself. If not to 1912, then maybe you trace the self-driving car to 1940 and the practical Oldsmobile Hydra-Matic transmission. Surely a car that shifts its own gears is a forerunner to a self-driver. And if not GM, then you might credit Chrysler and its “Auto pilot” feature introduced in 1958. Sure, the marketing folks who named it may have over-promised a bit, but that early cruise control system certainly was an essential step toward autonomy.

Much more sophisticated systems entered the market in the last decade or so. Lexus gave us “Dynamic Laser Cruise Control” with the 2000 LS 430. This device not only maintained a regular driving speed, it also automatically slowed or stopped the car in reaction to traffic ahead. (It also proved that fancy marketing names were still very much in style.) Adaptive cruise control, like the technologies before it, made its way from luxury marques to more modest models and is now a rather widely available option. The same is true of parking assist systems, in which the car can steer itself into a parking space. They first appeared in Lincoln and Lexus models, and then migrated to Ford and Toyota offerings.

“Active lane keeping” appears to be the big story for 2014. We’ve had passive systems, in which an alarm sounds if the driver weaves or drifts, for ten years, but “active” systems are just that – active. Infiniti’s Q50 will steer itself should the driver let go of the wheel while at speed, even through broad curves. The feature is a combination of camera and radar units that “read” the road and a “drive by wire” setup through which the front wheels are steered by motors wired to the steering wheel. (There’s no mechanical connection between the front wheels and the steering wheel.) Granted, it’s up to you to get the car on and off the freeway but, while there and with the cruise control and lane keeping engaged, the Q50 essentially drives itself.

Infiniti stresses that its active lane keeping is a driver assist system. It’s meant to ease the burden rather than take it all, but that’s no different than any of its technological predecessors. All of these devices seem destined to meld into a fully functional autonomous car some day, and that day might just be sooner than any of us think.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford

Report from the Goodwood Revival

For three days, September 13-15, the clock turned back to the glory days of postwar British motorsport at the inimitable Goodwood Revival. Racing, aviation, music and vintage fashions of the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s came together on the Goodwood race circuit, outside Chichester, England, for what may well be the world’s premier historic automobile event. As in past years, the 2013 Goodwood Revival spotlighted a legendary race driver. Jim Clark, the Scottish wunderkind who won 25 races and two Formula One world championships before he died in a 1968 racing accident, took center stage this year. Clark’s groundbreaking win at the 1965 Indianapolis 500 is among his best-known victories, and The Henry Ford brought to Goodwood the Lotus-Ford Type 38 that he drove that day.

Once each day during the event, 36 cars associated with Clark’s career gathered on the track for an exciting parade lap around the 2.4-mile circuit. Dario Franchitti, a devoted Jim Clark fan and a three-time Indy 500 winner, drove our Type 38 in the parade. Some of Clark’s contemporaries, including Sir Jackie Stewart and John Surtees, also drove parade cars, making the tribute particularly special.

Significant though it was, the Jim Clark program was only one element at this year’s revival. Of particular interest to me was the 50th anniversary celebration of Ford’s GT40. Goodwood brought together 40 such cars, 27 of which competed in a 45-minute race complete with a mid-contest driver change. The GT40 dominated Le Mans in the late 1960s, and Goodwood’s collection included chassis #1046, the car that won the 1966 24-hour and started Ford’s reign. Appropriately enough, Goodwood displayed #1046 and several of its siblings in a recreation of the Le Mans pit building where they looked right at home.

Goodwood’s airfield housed two Royal Air Force fighter squadrons during World War II, so it’s only natural that vintage aircraft have a presence at the Revival too. The most impressive exhibit this year – for sheer size if nothing else – was a German-built 1936 Junkers JU 52. (With its three engines and corrugated aluminum skin, it bore more than a passing resemblance to a certain Ford aircraft of a decade earlier.) The Junkers flew several demonstration loops around the Goodwood grounds on Sunday. Few things can divert your attention from a vintage motor race, but a 1936 airplane with a 97-foot wingspan flying overhead will do it!

The Goodwood Revival is a magical experience. With so many historic automobiles and airplanes around you, and so many of the visitors and participants attired in period clothing, it’s quite easy to get lost in time. That wonderful vintage atmosphere is one of the two strongest memories I take from this year’s event. The other is of people jumping back startled whenever our Type 38 fired up. After all, 495 horses make a lot of noise!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford

events, race car drivers, Goodwood Revival, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson, racing, cars, car shows, airplanes

Jim Clark and the Win That Changed Indy

The Indianapolis 500 is America’s premier motorsports event. Since its inaugural run in 1911, Indy has exemplified our country’s obsession with speed. It is ironic, then, that one of its most significant victories came from a Scottish driver in a British-built (though American-powered) car. In one fell swoop, Jim Clark’s 1965 win in the Lotus-Ford Type 38 marked the end of the four-cylinder Offenhauser engine’s dominance, the end of the front engine, and the incursion of European design into the most American of races. The Henry Ford holds many important objects, photographs and documents that tell this fascinating story.

By the early 1960s, four-cylinder roadsters were an ingrained tradition at the Indianapolis 500. Race teams were hesitant to experiment with anything else. American driver Dan Gurney, familiar with the advanced Formula One cars from the British firm Lotus, saw the potential in combining a lithe European chassis with a powerful American engine. He connected Lotus’s Colin Chapman with Ford Motor Company and the result was a lightweight monocoque chassis fitted with a specially designed Ford V-8 mounted behind the driver. Scotsman Jim Clark, Team Lotus’s top driver, took the new design to an impressive second place finish at Indy in 1963. While Clark started strong in the 1964 race, having earned pole position with a record-setting qualifying time, he lost the tread on his left rear tire, initiating a chain reaction that collapsed his rear suspension and ended his race early.

Based on his past performances, Jim Clark entered the 1965 race as the odds-on favorite. Ford was especially eager for a win, though, and sought every advantage it could gain. The company brought in the Wood Brothers to serve as pit crew. The Woods were legendary in NASCAR for their precision refueling drills, and they were no less impressive at Indianapolis where they filled Clark’s car with 50 gallons in less than 20 seconds. This time, the race was hardly a contest at all. Clark led for 190 of the race’s 200 laps and took the checkered flag nearly two minutes ahead of his nearest rival. Jim Clark became the first driver to finish the Indianapolis 500 with an average speed above 150 mph (he averaged 150.686) and the first foreign driver to win since 1916. The race – and the cars in it – would never be the same.

Many of The Henry Ford’s pieces from Clark’s remarkable victory are compiled in a special Expert Set on our Online Collections page. The most significant artifact from the 1965 race is, of course, car #82 itself. Jim Clark’s 1965 Lotus-Ford Type 38 joined our collection in 1977 and has been a visitor favorite ever since. Dan Gurney, who brought Lotus and Ford together, shared his reminiscences with us in an interview in our Visionaries on Innovation series. The Henry Ford’s collection also includes a set of coveralls worn by Lotus mechanic Graham Clode at the 1965 race, and a program from the 1965 Victory Banquet signed by Clark himself.

Photographs in our collection include everything from candid shots of Gurney, Chapman and Clark to posed portraits of Clark in #82 at the Brickyard. The Henry Ford’s extensive Dave Friedman Photo Collection includes more than 1,400 images of the 1965 Indianapolis 500 showing the countless cars, drivers, crew members and race fans that witnessed history being made. Finally, the Phil Harms Collection includes home movies of the 1965 race with scenes of Clark’s car rolling out of the pit lane, running practice and qualifying laps, and leading the pack in the actual race.

Jim Clark died in a crash at the Hockenheim race circuit in Germany in 1968. It was a tragic and much-too-soon end for a man still considered to rank among the greatest race drivers of all time. The Henry Ford is proud to preserve so many pieces from his seminal Indianapolis 500 win.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford

Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Indy 500, by Matt Anderson

The Car Guy's Ultimate Beach Party

The Henry Ford just returned from the Pebble Beach Concours d'Elegance, on California’s Monterey Peninsula, where our 1950 Lincoln Presidential Limousine took part in this year’s spotlight on Lincoln custom coachwork. As a curator, I was gratified by the strong reaction the crowd had to the limo, used by Presidents Truman, Eisenhower and Kennedy. Pebble Beach regularly features some of the most beautiful cars in the world, so the Lincoln’s popularity speaks highly about the power in that car’s story. (My single favorite reaction was from a man who turned to his friend and, with genuine awe, stated, “The Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force sat in that very seat!” Clearly, he likes Ike.)

While the concours is the centerpiece, Pebble Beach is in fact a week-long celebration of all things automotive. In the days leading up to the show, car makers and insurers host receptions and displays; nearby Mazda Raceway Leguna Seca stages competitions for vintage race cars; and auction houses sell exceptional vehicles at equally impressive prices. (This year a rare 1967 Ferrari sold for a cool $27.5 million – an all-time record for a car at a U.S. auction.)

For me, the highlight of the pre-concours events was a visit to The Quail. This motorsports gathering, which marked its 11th year, brings together the rarest and most exclusive automobiles in the world. While the Pebble Beach concours glitters with Lincolns and Packards, along with Porsches and Ferraris, The Quail adds names like Bugatti, Maserati and Lamborghini to the mix. It’s truly the best of the best.

It is a great treat for any automobile fan to visit the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance, and even more so to participate with a car. I’m so pleased that we were able to share a part of The Henry Ford’s matchless collection at what may be motoring’s foremost event.

By Matt Anderson, Curator of Transportation

Last month, staff and volunteers from car museums across the United States gathered in Lincoln, Neb., for the 2013 Annual Conference of the National Association of Automobile Museums (NAAM). The three-day meeting offers a chance to reconnect with friends and colleagues, visit interesting collections, and commiserate on the latest happenings in the world of car museums.

Our host in Lincoln was the fantastic Smith Collection Museum of American Speed. Founded in 1992 by “Speedy” Bill and Joyce Smith (the proprietors of Speedway Motors, among the country’s top performance parts dealers), the museum’s great strength is its collection of early American race cars and 300+ race engines. The Smith team treated us to a wonderful “all access” evening in their 135,000 square-foot facility.

Conference sessions covered everything from fundamentals (museum mission statements and strategic plans) to esoteric details only a curator or registrar could love (proper file formats and sizes for the digital imaging of museum collections). As always, vehicle preservation was a hot topic, and The Henry Ford’s Senior Conservator Clara Deck presented on her efforts in preparing cars for our Driving America exhibit.

And speaking of Driving America - The highlight of any NAAM conference is the award ceremony that wraps it all up. Each year NAAM recognizes select programs, publications and exhibits that represent the best in American automobile museums. I’m proud to report that, this year, the judges selected Driving America for the NAAMY Award of Excellence for Interpretive Exhibits. It’s a wonderful honor, and we are grateful to our colleagues for the recognition.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford

Guest Judging at Detroit Autorama 2013

Over the weekend of March 9-10, I had the pleasure of serving as a guest judge at the 2013 Detroit Autorama. The show, which features some of the best hot rods and custom cars in the country, is to car guys what the World Series is to baseball fans. My task was to select the winner of the CASI Cup, a sort of “sponsor’s award” given by Championship Auto Shows, Inc., Autorama’s producer.

I’d like to say that I entered Cobo Center and got straight to work, diligently focused on my duties. But it would be a lie! I quickly got distracted by the amazing vehicles. There was “Root Beer Float,” the ’53 Cadillac named for its creamy brown paint job. There was the ’58 Edsel lead sled with its chrome logo letters subtly rearranged into “ESLED.” There was the famous Monkeemobile built by Dean Jeffries. And, from my own era, there was a tribute car modeled on Knight Rider’s KITT. (You’ve got to admire someone who watched all 90 episodes – finger ever on the pause button – so he could get the instrument panel details just right.)

Every vehicle was impressive in its own way, whether it was a 100-point show car or a rough and rusted rat rod. In the end, though, my pick for the CASI Cup spoke to my curator’s soul. Dale Hunt’s 1932 Ford Roadster was, to my mind, the ultimate tribute car. It didn’t honor one specific vehicle – it honored the rodder’s hobby itself.

Hunt built his car to resemble the original hot rods, the fenderless highboy coupes that chased speed records on the dry lakes of southern California. The car’s creative blend of parts and accessories – the ’48 Ford wheel covers, the stroked and bored Pontiac engine, the lift-off Carson top – all spoke to the “anything goes” attitude that is at the heart of hot rodding and customizing to this day.

It was a privilege to be a part of the show. Like most of the fans walking the floor with me, I’m already looking forward to Autorama 2014!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2010s, Michigan, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, Autorama

This year brings a couple of notable – and not particularly pleasant – anniversaries for Studebaker fans. Fifty years ago, in December 1963, the company closed its operations in South Bend, Ind. – where brothers J.M., Clement, Henry, Peter and Jacob founded the venerable firm more than 100 years before. While Studebaker built cars in Canada for a few more years, many say that the company really ended when it left its longtime home.

We also mark the anniversary of an earlier corporate struggle. Eighty years ago this month, Studebaker filed for bankruptcy. While many car companies went under during the Great Depression – and few recovered – Studebaker’s bankruptcy is a particularly sad story of poor management and human tragedy.

Albert Erskine joined Studebaker as treasurer in 1911 and assumed its presidency in 1915. He cut prices and boosted sales, leading to generally good years for Studebaker marked by stylish vehicles and progressive labor relations.

When the Depression hit and sales crashed, Erskine turned to South Bend’s closest thing to a superhero: Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne. The football legend died in a 1931 plane crash, and Erskine named Studebaker’s new line of small, affordable automobiles “Rockne” is his honor. The Rockne was well-equipped for an inexpensive car and early sales were promising. But rather than concentrate all production in South Bend, Erskine built most of the Rocknes in Detroit. The two factories strained Studebaker’s shaky finances.

More troubling was Erskine’s insistence on paying high dividends to stockholders even in the Depression’s worst years. While other car companies hoarded cash to ride out the storm, Studebaker burned through it. Erskine simply refused to believe that the Great Depression was anything more than an economic hiccup.

Inevitably, Studebaker ran out of cash and, on March 18, 1933, entered receivership. Erskine was pushed out of the presidency in favor of more cost-conscious managers. His successors engineered a brilliant turnaround and led Studebaker out of receivership in two years. Sadly, Erskine’s ending was quite different. With his job gone, his Studebaker stock worthless, his personal debts mounting and his health failing, Erskine took his own life on July 1, 1933. While he may not have been wholly responsible – clearly the Board of Directors failed in its oversight – Albert Erskine paid the ultimate price for Studebaker’s ordeal.

Take a look at more of our Studebaker artifacts in our online Collections.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.