Posts Tagged by matt anderson

1917 Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” Biplane

The Curtiss JN-4 always turns heads in “Heroes of the Sky.” / THF39670

The Curtiss JN-4 always turns heads in “Heroes of the Sky.” / THF39670Walk into the barnstormers section of our Heroes of the Sky exhibit and odds are the first airplane to catch your eye will be our 1917 Curtiss JN-4 “Canuck” biplane. Whether it’s the airplane’s inverted attitude, its dangling wing-walker, or its fishy-looking fuselage, there’s a lot to draw your attention. And well there should be. The Curtiss Jenny was among the most significant early American airplanes.

Conceived by British designer Benjamin D. Thomas and built by American aviation entrepreneur Glenn Curtiss, the JN airplanes combined the best elements of Thomas’s earlier Model J and Curtiss’s earlier Model N trainer planes. New variants of the JN were increasingly refined. The fourth in the series, introduced in 1915, was logically designated JN-4. Pilots affectionately nicknamed it the “Jenny.” The inspiration is obvious enough, but even more so if you imagine the formal model name (JN-4) written as many flyers first saw it—with an open-top “4” resembling a “Y.”

This Curtiss JN, circa 1915, left no doubt about its manufacturer’s identity. / THF265971

Despite not being a combat aircraft, the Curtiss Jenny became the iconic American airplane of the First World War. Some 6,000 units were built, and nine of every ten U.S. military pilots learned to fly on a Jenny. The model’s low top speed (about 75 mph) and basic but durable construction were ideal for flight instruction. Dual controls in the front and back seats allowed teacher or student to take charge of the craft at any time.

Our JN-4 is one of approximately 1,200 units built under license by Canadian Aeroplanes, Ltd., of Toronto. In a nod to their Canadian origins, these airplanes were nicknamed “Canucks.” While generally resembling American-built Jennys, the Canadian planes have a different shape to the tailfin and rudder, a refined tail skid, and a control stick rather than the wheel used stateside. (The stick became standard on later American-built Jennys.)

Barnstormer “Jersey” Ringel posed while (sort of) aboard his Jenny about 1921. / THF135786

Following the war, many American pilots were equally desperate to keep flying and to earn a living. “Barnstorming”—performing death-defying aerial stunts for paying crowds—offered a way to do both. Surplus military Jennys could be bought for as little as $300. The same qualities that suited the planes to training—durability and reliability—were just as well-suited to stunt flying. The JN-4 became the quintessential barnstormer’s plane, which explains why our Canuck is featured so prominently in the Heroes of the Sky barnstorming zone. As for the inspiration behind our plane’s paint job… that’s another kettle of fish.

Fishing lures, similar to this one, inspired the unusual paint scheme on our Curtiss JN-4. / THF150858

Founded in 1902, James Heddon and Sons produced fishing lures and rods at its factory in Dowagiac, Michigan. Heddon’s innovative, influential products helped it grow into one of the world’s largest tackle manufacturers. That inventive streak spilled over into Heddon’s advertising efforts. In the early 1920s, the company acquired two surplus JN-4 Canucks and painted them to resemble Heddon lures. These “flying fish” toured the airshow circuit to promote Heddon and its products. While our Canuck isn’t an original Heddon plane, it’s painted as a tribute to those colorful aircraft. (Incidentally, the Heddon Museum is well worth a visit when you’re in southwest Michigan.)

Every airplane in Heroes of the Sky has a story to tell. Some of them are even fish stories!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Additional Readings:

- Getting into the Air: Alexander Graham Bell’s Aerial Experiment Association

- A Stunt-Flying Aviatrix

- 1939 Sikorsky VS-300A Helicopter

- A Closer Look: Air Traffic Control Radar Scope

World War I, Canada, 20th century, 1910s, popular culture, Heroes of the Sky, Henry Ford Museum, flying, by Matt Anderson, airplanes

Mcity Driverless Shuttle: The Human Side of AV Tech

The Mcity Driverless Shuttle arrives at The Henry Ford.

Thanks to a generous gift from the University of Michigan (U-M), The Henry Ford recently acquired its second autonomous vehicle: a driverless shuttle used by U-M’s Mcity connected and automated vehicle research center. Readers may recall that we acquired our first AV in 2018 – a 2016 General Motors Self-Driving Test Vehicle. While the GM car was an experimental vehicle focused on technology, the Mcity shuttle took part in an intriguing project more focused on the psychology of consumer trust and acceptance of driverless vehicles.

From June 4, 2018, through December 13, 2019, Mcity, a public-private research partnership led by U-M, operated this driverless shuttle at U-M’s North Campus Research Complex in Ann Arbor. The project’s purpose was to understand how passengers, pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers interacted with autonomous vehicles. In effect, the project was a way to gauge consumer acceptance of a decidedly unconventional new technology.

The shuttle donated to The Henry Ford is one of two fully-automated, electrically-powered, 11-seat shuttles Mcity operated on a fixed route around the research complex throughout the course of the study. The shuttles were built by French manufacturer Navya. In late 2016, Navya had delivered its first self-driving shuttle in North America to Mcity, where it was used to support research and to demonstrate automated vehicle technology. In June 2017, Mcity announced plans to launch a research project in the form of an on-campus shuttle service that would be open to the U-M community.

The Mcity Driverless Shuttle operated on a one-mile loop around the North Campus Research Complex at speeds averaging about 10 miles per hour. The service ran Monday-Friday from 9 AM to 3 PM. While its route avoided heavy-traffic arteries, the shuttle nevertheless shared two-way public roadways with cars, bicycles, and pedestrians. It operated in a variety of weather conditions, including winter cold and snow; but was not used in more extreme weather, such as heavy snow or rain.

The Mcity Driverless Shuttle on its route at the University of Michigan’s North Campus Research Complex. (Photo credit: University of Michigan)

While the shuttle and its technology are impressive enough, the impetus behind its use is arguably more important to The Henry Ford. The Mcity research project was the first driverless shuttle deployment in the United States that focused primarily on user behavior. Mcity’s goal was to learn more about how people reacted to AVs, rather than prove the technology. The two shuttles were equipped with exterior video recorders to capture reactions from people outside the shuttle, and interior video and audio recorders to capture reactions from passengers inside. On-board safety conductors, there to stop the shuttle in case of emergency, also observed rider behavior.

Mcity staff monitored ridership numbers and patterns throughout the project, and riders were encouraged to complete a survey about their experience that was developed by Mcity and the market research firm J.D. Power. Survey questions ranged from basic inquiries about age and relationship to the university, to more specific inquiries about reasons for riding, degree of satisfaction with the service, interest level in AV technology, and – most significantly – degree of trust in the shuttle and its driverless capabilities. The survey data was then analyzed by J.D. Power. You can learn more about the results through Mcity's white paper, "Mcity Driverless Shuttle: What We Learned About Consumer Acceptance of Automated Vehicles."

Along with the shuttle itself, U-M has kindly donated examples of the special signage installed by Mcity in support of the shuttle project. There are no current government regulations – at the federal, state, or local levels – for signage along a driverless vehicle route. Mcity developed its own signs to alert other road users to the shuttle’s presence. Samples include signs proclaiming “Shuttle Stop” and “Attention: Driverless Vehicle Route.”

Autonomous vehicles are coming to our streets – it’s no longer a question of “if,” but of “when.” Indeed, the Mcity shuttle project proves that AVs are, to an extent, already here. These driverless vehicles promise to be the most transformative development in ground transportation since the automobile itself. Self-driving capabilities will fundamentally change our relationship with the vehicle. The technology promises improved safety and economy in our cars and buses, greater capacity and efficiency on our roads, and enhanced mobility and quality of life for those unable to drive themselves. The Mcity Driverless Shuttle represents an important milestone on the road to autonomy, and it marks an important addition to The Henry Ford’s automotive collection.

Continue Reading

21st century, 2010s, technology, research, Michigan, by Matt Anderson, autonomous technology, alternative fuel vehicles

The Railroad Roundhouse

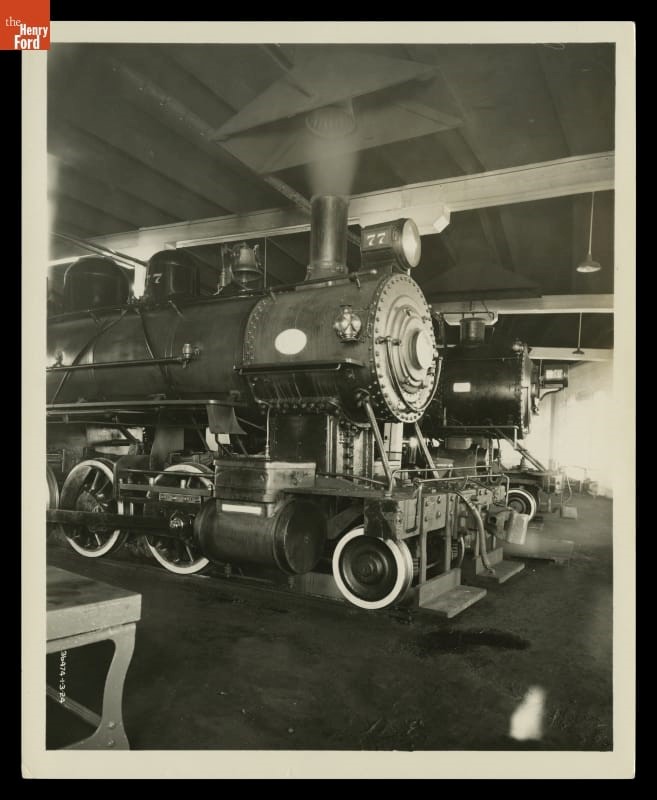

The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse in Greenfield Village. (THF2001)

Symbolic Structure

Apart from the ubiquitous small-town depot, there may be no building more symbolic of railroading than the roundhouse. At one time, thousands of these peculiar structures were spread across the country. Inside them, highly-skilled workers used specialized tools, equipment, and techniques to care for the steam locomotives that powered American railroads for more than a century.

Today, only a handful of American roundhouses are still in regular use maintaining steam locomotives. Visitors to The Henry Ford have the rare opportunity to see one of these buildings in action. The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse is the heart of our Weiser Railroad, the steam-powered excursion line that transports guests around Greenfield Village. Our dedicated railroad operations team maintains our operating locomotives using many of the same methods and tools as their predecessors of earlier generations.

Workers pose outside the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse on its original site in Marshall, Michigan, circa 1890-1900. (THF129728)

Roundhouses were built wherever railroads needed them, whether in the heart of a large city or out on the open plains. In 1884, the Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Railroad constructed its roundhouse in Marshall, Michigan – the approximate midpoint on DT&M’s 94-mile line between the Michigan cities of Dundee and Allegan. Larger railroads operated multiple roundhouses, generally located at 100-mile intervals – roughly the distance one train crew could travel in a single shift. The roundhouses on these large railroads served as relay points where a new locomotive (and crew) took over the train while the previous locomotive went in for maintenance.

Roundhouses gave crews space to work, but also kept locomotives and equipment within easy reach, as seen in this 1924 view inside a Detroit, Toledo & Ironton Railroad roundhouse. (THF116641)

Circular Reasoning

Railroads embraced the circular roundhouse design for a variety of reasons. It allowed for a compact layout, keeping the locomotives and equipment inside closely spaced and within accessible reach. The building pattern was flexible, permitting a railroad to add stalls to an existing roundhouse (or remove them) as conditions warranted. The turntable – used to access each roundhouse stall – simplified trackwork and didn’t require multiple switches to move locomotives from place to place.

Not all “roundhouses” were round. See this example from Massachusetts, photographed in 1881. But round structures offered decided advantages over rectangular buildings. (THF201503)

Likewise, the single-space stalls and turntable allowed for convenient access to any one locomotive. Long, rectangular service buildings required moving several locomotives to extract one located at the end of a track. (If you’ve ever had to ask people to move their cars from a driveway so that you could get yours out, then you’ll recognize this problem.) The turntable had the added benefit of being able to reverse the direction of a locomotive without the need for a space-consuming “wye” track.

People made the roundhouse work, like this man at the Detroit, Toledo & Ironton’s Flat Rock, Michigan, roundhouse photographed in 1943. (THF116647)

A Variety of Trades

Of course, roundhouses were more than locomotives, turntables, and tracks. Their most important feature was the variety of skilled tradespeople and unskilled workers who made them function. Boilermakers, blacksmiths, machinists, pipefitters, and more all labored within a roundhouse’s stalls. Large roundhouses might employee hundreds of people. The environment was noisy and smoky, and much of the work was dangerous and dirty – emptying ash pans, cleaning scale from boilers, greasing rods and fittings – but it had its advantages. Unlike train crews who worked all hours and spent long periods away from home, roundhouse workers enjoyed more regular schedules and returned to their own beds at the end of the day.

Roundhouses faded after the transition from steam to diesel, illustrated by this 1950 photo taken at Ford’s Rouge plant. (THF285460)

Roundhouses Retired

With the widespread adoption of diesel-electric locomotives following World War II, the roundhouse gradually disappeared from the American railroad. Diesels needed far less maintenance than steam engines, and required fewer specialized skills from the crews that serviced them. Following dieselization, a few roundhouses were modified to maintain the new locomotives, while others were put to other railroad uses. Some were preserved as museums, and a few were even converted into shopping centers or restaurants. But most were simply torn down or abandoned.

The Detroit, Toledo & Milwaukee Roundhouse followed a similar pattern of slipping into disuse – though in its case, it was more a victim of the DT&M Railroad’s failing fortunes than the transition to steam. After a series of acquisitions and mergers, the little DT&M became a part of the Michigan Central. The much larger MC had no need for DT&M’s Marshall roundhouse, and the new owner repurposed the structure into a storage building. In 1932, the roundhouse was abandoned altogether. It was in a dilapidated condition by the late 1980s, when The Henry Ford began the process of salvaging what components we could. After many years of planning and fundraising, the reconstructed DT&M Roundhouse opened to Greenfield Village guests in 2000. Clearly, the building itself is rare enough, but it’s the work that goes on inside that makes it truly special. Today, the DT&M Roundhouse is one of the few places in the world where visitors can still observe the crafts and skills that kept America’s steam railroads rolling so many years ago.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

20th century, 19th century, railroads, Michigan, Greenfield Village buildings, Greenfield Village, by Matt Anderson

1953 Ford Sunliner Pace Car

The 1953 Ford Sunliner, Official Pace Car of the 1953 Indianapolis 500. (THF87498)

As America’s longest-running automobile race, it’s not surprising that the Indianapolis 500 is steeped in special traditions. Whether it’s the wistful singing of “Back Home Again in Indiana” before the green flag, or the celebratory Victory Lane milk toast – which is anything but milquetoast – Indy is full of distinctive rituals that make the race unique. One of those long-standing traditions is the pace car, a fixture since the very first Indy 500 in 1911.

This is no mere ceremonial role. The pace car is a working vehicle that leads the grid into the start of the race, and then comes back out during caution laps to keep the field moving in an orderly fashion. Traditionally, the pace car’s make has varied from year to year, though it is invariably an American brand. Indiana manufacturers like Stutz, Marmon, and Studebaker showed up frequently, but badges from the Detroit Three – Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors – have dominated. In more recent years, Chevrolet has been the provider of choice, with every pace car since 2002 being either a Corvette or a Camaro. Since 1936, the race’s winning driver has received a copy of pace car as a part of the prize package.

Amelia Earhart rides in the pace car, a 1935 Ford V-8, at the 1935 Indianapolis 500. (THF256052)

Likewise, honorary pace car drivers have changed over time. The first decades often featured industry leaders like Carl Fisher (founder of Indianapolis Motor Speedway), Harry Stutz, and Edsel Ford. Starting in the 1970s, celebrities like James Garner, Jay Leno, and Morgan Freeman appeared. Racing drivers have always been in the mix, with everyone from Barney Oldfield to Jackie Stewart to Jeff Gordon having served in the role. (The “fastest” pace car driver was probably Charles Yeager, who drove in 1986 – 39 years after he broke the sound barrier in the rocket-powered airplane Glamorous Glennis.)

Ford was given pace car honors for 1953. It was a big year for the company – half a century had passed since Henry Ford and his primary shareholders signed the articles of association establishing Ford Motor Company in 1903. The firm celebrated its golden anniversary in several ways. It commissioned Norman Rockwell to create artwork for a special calendar. It built a high-tech concept car said to contain more than 50 automotive innovations. And it gave every vehicle it built that year a commemorative steering wheel badge that read “50th Anniversary 1903-1953.”

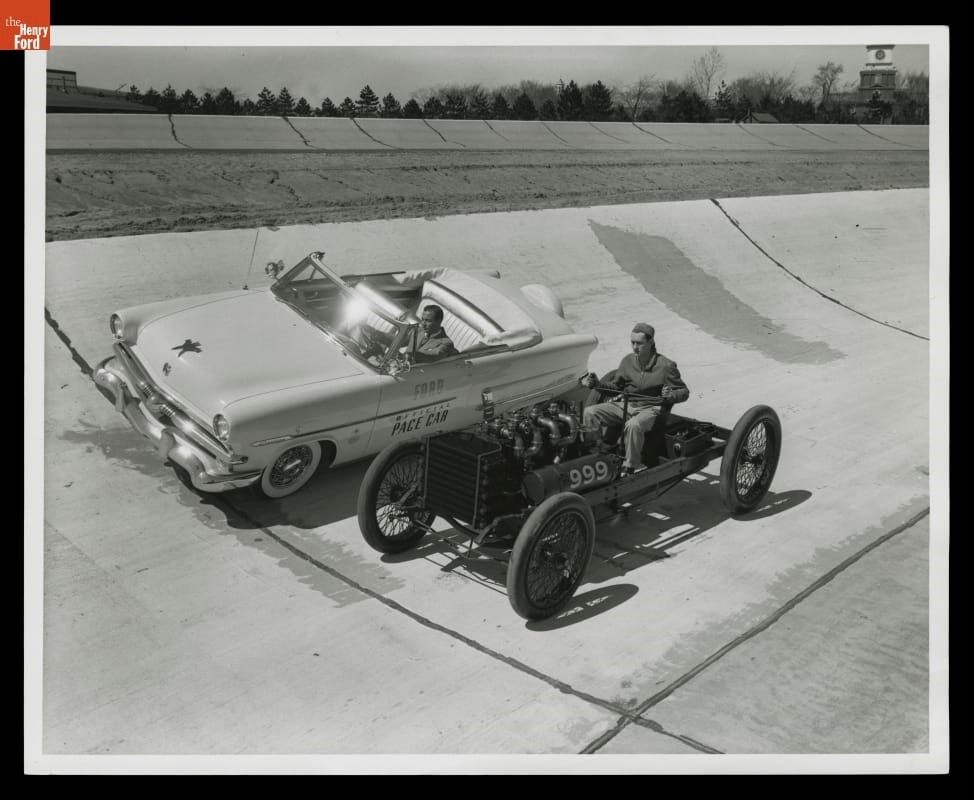

Henry Ford’s 1902 “999” race car poses with the 1953 Ford Sunliner pace car on Ford’s Dearborn test track. (Note the familiar clocktower at upper right!) (THF130893)

For its star turn at Indianapolis, Ford provided a Sunliner model to fulfill the pace car’s duties. The two-door Sunliner convertible was a part of Ford’s Crestline series – its top trim level for the 1953 model year. Crestline cars featured chrome window moldings, sun visors, and armrests. Unlike the entry-level Mainline or mid-priced Customline series, which were available with either Ford’s inline 6 or V-8 engines, Crestline cars came only with the 239 cubic inch, 110 horsepower V-8. Additionally, Crestline was the only one of the three series to include a convertible body style.

William Clay Ford at the tiller of “999” at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. (THF130906)

Ford actually sent two cars to Indianapolis for the big race. In addition to the pace car, Henry Ford’s 1902 race car “999” was pulled from exhibit at Henry Ford Museum to participate in the festivities. True, “999” never competed at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. But its best-known driver, Barney Oldfield, drove twice in the Indy 500, finishing in fifth place both in 1914 and 1916. Fittingly, Indy officials gave William Clay Ford the honor of driving the pace car. Mr. Ford, the youngest of Henry Ford’s grandchildren, didn’t stop there. He also personally piloted “999” in demonstrations prior to the race.

As for the race itself? The 1953 Indianapolis 500 was a hot one – literally. Temperatures were well over 90° F on race day, and hotter still on the mostly asphalt track. Many drivers actually called in relief drivers for a portion of the race. After 3 hours and 53 minutes of sweltering competition, the victory went to Bill Vukovich – who drove all 200 laps himself – with an average race speed of 127.740 mph. It was the first of two consecutive Indy 500 wins for Vukovich. Sadly, Vukovich was killed in a crash during the 1955 race.

Another view of the 1953 Ford Sunliner pace car. (THF87499)

Following the 1953 race and its associated ceremonies, Ford Motor Company gifted the original race-used pace car to The Henry Ford, where it remains today. Ford Motor also produced some 2,000 replicas for sale to the public. Each replica included the same features (Ford-O-Matic transmission, power steering, Continental spare tire kit), paint (Sungate Ivory), and lettering as the original. Reportedly, it was the first time a manufacturer offered pace car copies for purchase by the general public – something that is now a well-established tradition in its own right.

Sure, the Sunliner pace car is easy to overlook next to legendary race cars like “Old 16,” the Lotus-Ford, or – indeed – the “999,” but it’s a special link to America’s most important auto race, and it’s a noteworthy part of the auto racing collection at The Henry Ford.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Indiana, 20th century, 1950s, racing, race cars, Indy 500, Ford Motor Company, convertibles, cars, by Matt Anderson

Be Empathetic like AAA

THF171209 / Automobile Club of Michigan Sign

It was my privilege to take over The Henry Ford’s Twitter feed for a while on the morning of May 14. Our theme for the day was "Be Empathetic." To me that means "be helpful and supportive," and those attributes remind me of early auto organizations like the Automobile Club of Michigan, founded in 1916. The Automobile Club of Michigan is one of several regional organizations that joined the American Automobile Association. Over the years, AAA’s work has included advocating for better roads, providing roadside assistance to stranded motorists, encouraging traffic safety generally – particularly near schools, and promoting tourism and travel by car throughout the United States. During my Twitter session, I shared several AAA items in the collections of The Henry Ford.

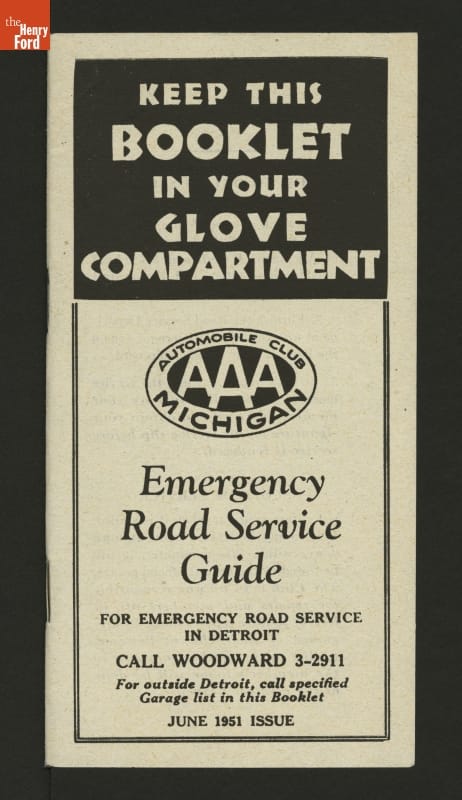

To the Rescue on the Road

THF103500 / Pamphlet from AAA of Michigan, "Emergency Road Service Guide," June 1951 / front

AAA began offering emergency roadside service in 1915. This 1951 pamphlet lists affiliated service garages throughout Michigan.

THF333431 / 1947 Ford Repair Truck at the Ralph Ellsworth Dealership, Garden City, Michigan, October 1946

This photo shows one of the AAA-affiliated wreckers that might've come to your aid in the late 1940s or early 1950s. In this case, it's a 1947 Ford.

THF304296 / Toy Truck, Used by James Greenhoe, 1937-1946

Children could play their own "roadside assistance" games with a toy truck like this one, made circa 1940.

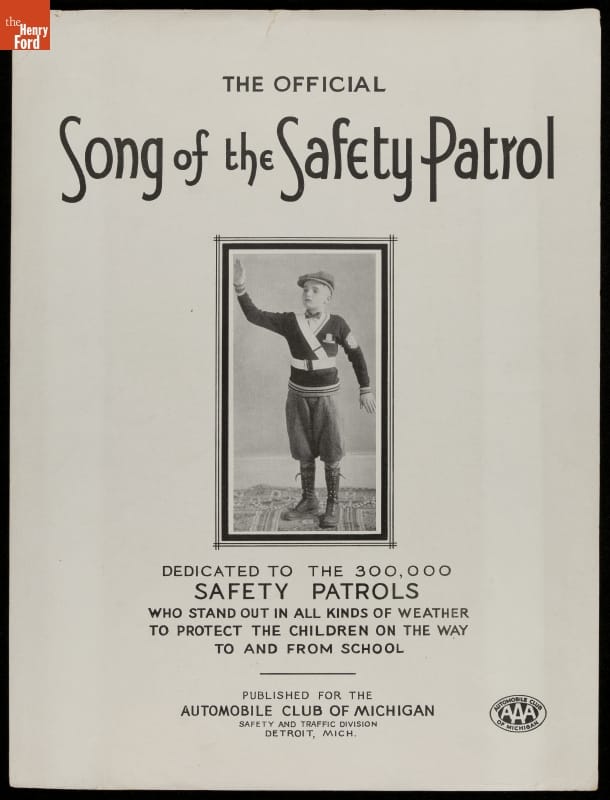

Keeping Children Safe

THF153486 / Automobile Club of Michigan Safety Patrol Armband, 1950-1960

Speaking of children, one of AAA's most important initiatives is its School Safety Patrol program, established in 1920.

THF208042 / Music Sheet, "The Official Song of the Safety Patrol," 1937

Safety patrollers help adults in protecting students at crosswalks, and in bus and car drop-off and pick-up zones. Their dedicated efforts were celebrated in "Song of the Safety Patrol" from 1937.

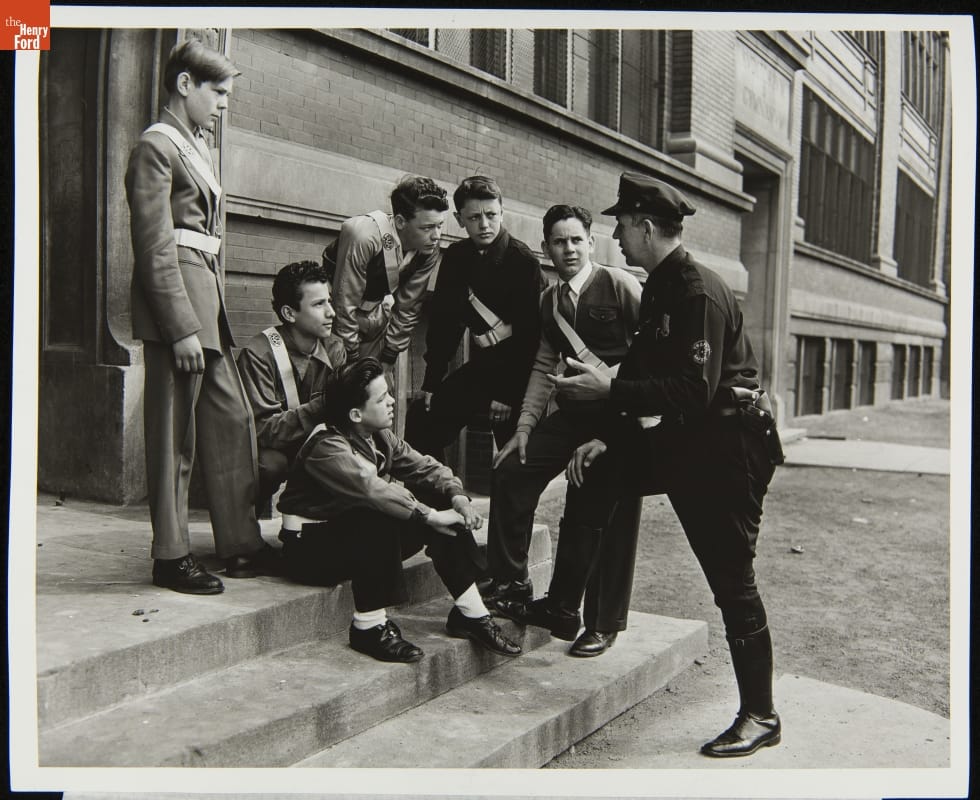

THF289667 / Detroit Police Officer Anthony Hosang Talks with Safety Patrol Students on a Tour of the Ford Rouge Plant, May 10, 1950

Here's a group of Detroit safety patrol members in 1950. They're listening to police officer Anthony Hosang as a part of a tour through Ford's Rouge Plant – a reward for a job well done.

Reaching Your Destination

THF104025 / "Official Highway Map of Michigan," Automobile Club of Michigan, 1934

AAA also helps drivers find their way by publishing road maps. Here's one showing the Detroit metro area in 1934. Many of the highway numbers are familiar, but their routes have changed.

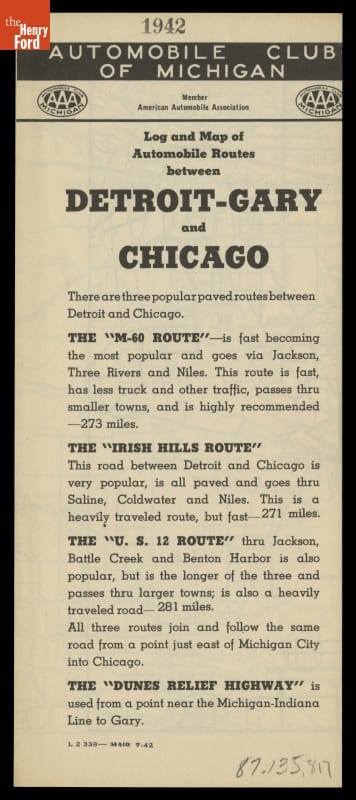

THF136038 / Log and Map of Automobile Routes between Detroit-Gary and Chicago, 1942

Here's a map of routes between Detroit and Gary-Chicago in 1942. The northern-most route (then U.S. 12) parallels modern I-94.

THF151706 / Automobile Club of Michigan, "Know Michigan Better, Stay Longer," Sign, 1950-1960

AAA also promotes tourism, encouraging drivers to explore America – and their own states. Residents can "know Michigan better," and visitors can "stay longer."

THF14793 / Travel Brochure for Holland Michigan, circa 1940

Springtime brings tulips, and what better place to enjoy them then Holland? (Holland, Michigan, that is.)

THF14744 / Souvenir Book, "Northern Michigan, Lower Peninsula," 1940

Here's a AAA guidebook promoting travel to Michigan's northern Lower Peninsula.

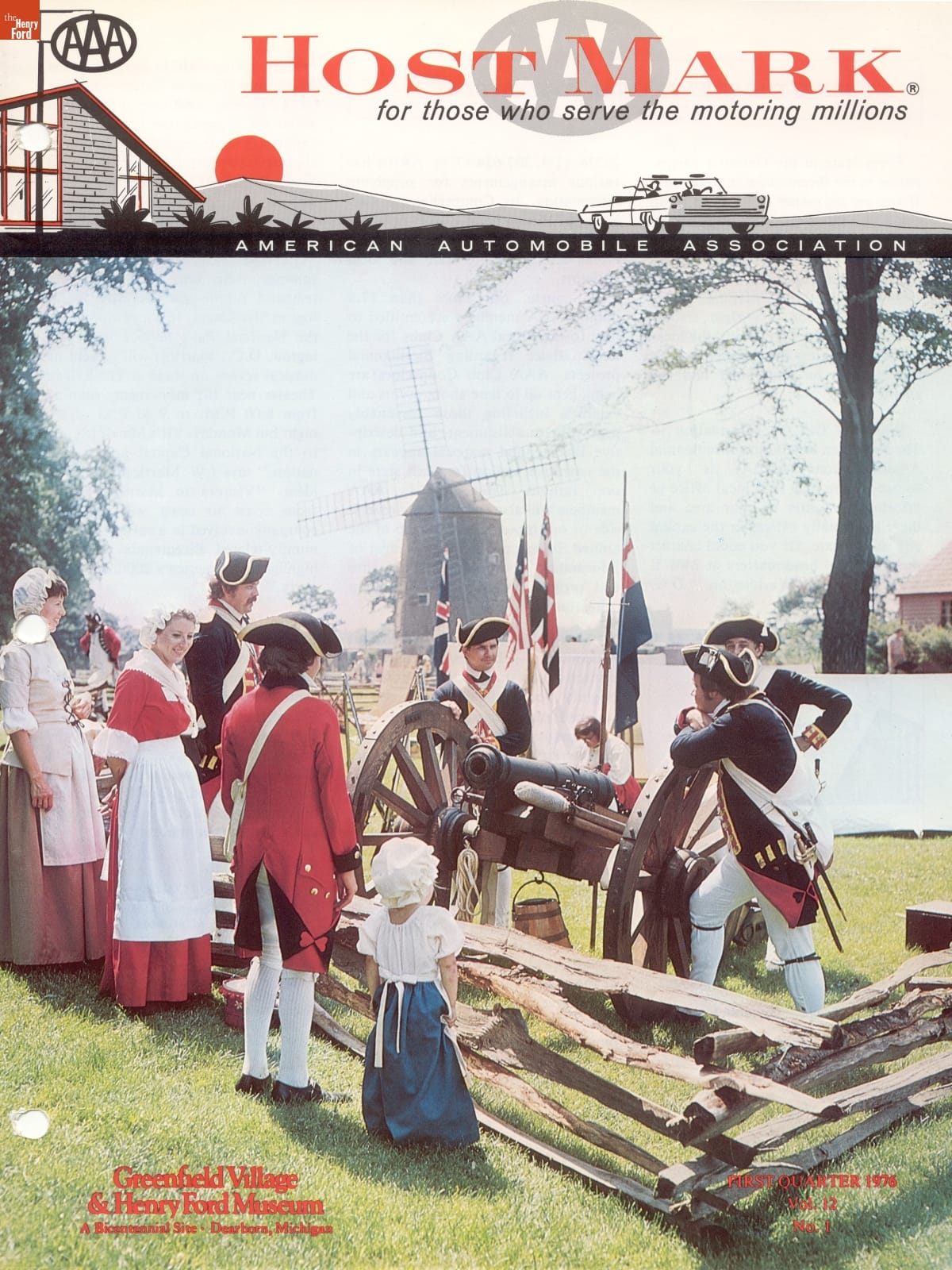

THF9103 / Host Mark Magazine, "Greenfield Village & Henry Ford Musem, A Bicentennial Site," 1976

And here's a familiar sight on the cover of AAA's Host Mark magazine. It's Greenfield Village, where bicentennial celebrations were underway throughout 1976.

It was great fun sharing these pieces with our Twitter followers. I also enjoyed answering some questions about our wider transportation holdings along the way. “Be Empathetic” – it’s an important lesson anytime, but especially right now.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

roads and road trips, travel, cars, by Matt Anderson, AAA, #THFCuratorChat

Conscious Conservation Is In

The concept of resourceful living is nothing new. Many people have been reducing, reusing and recycling for years. But now that we find ourselves in the midst of a global pandemic, it seems that “conspicuous consumption” is out and “conscious conservation” is in.

"How to Fix Your Bicycle". THF206623

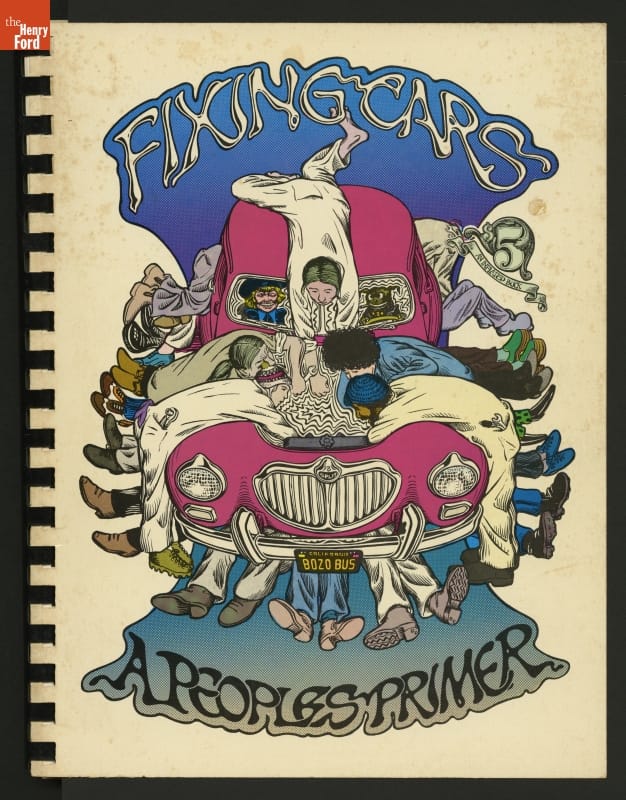

As we all learn to make do in our new world of social distancing and stay-at-home orders, here’s a look at how Americans have practiced resourceful living in the past. Whether it’s fixing the family car yourself, being proactive in your family’s health and well-being, or simply taking advantage of your extra at-home time to finally get organized, you’ll find much to inspire you in the collections of The Henry Ford.

In the Garage

The Railroad Roundhouse

“Fixing Cars, a People's Primer”

FIXD Car Diagnostic Sensor (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation

“Anybody’s Bike Book”

“How to Fix Your Bicycle”

“A Rough Guide to Bicycle Maintenance”

Improvisation & Fixing Things

Whole Earth Catalogs

Quilt Maker Susana Hunter

Susana Hunter (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Revisit the Break, Repair, Repeat: Spontaneous & Improvised Design exhibit, on view Summer 2019

Video Tour of the Exhibit

Expert Set (Highlight Artifacts from the Exhibit)

Press Coverage by The Detroit News

Staying Healthy & Keeping Germs at Bay

Phone Soap (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Anti-Germ Sponge (as seen on The Henry Ford's Innovation Nation)

Historic Soap and Household Detergent Packaging

Braniff International Airways Bar Soap

For Health, Food and Fun Keep a Garden

An Organized Workspace

Julia Child’s Kitchen

Overhead Drawing of Julia Child's Kitchen

L. Miller & Son Store Displays of Hardware

Hoosier-Style Kitchen Cabinet

Handy Helper Utility Cabinet

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Did you find this content useful? Consider making a gift to The Henry Ford.

home life, healthcare, by Matt Anderson, environmentalism, COVID 19 impact

2020 Detroit Autorama

With the North American International Auto Show now moved to June, we’ve had an unusually long dry spell in the Motor City when it comes to automotive exhibitions. The drought was finally broken by the annual Detroit Autorama, held February 28-March 1. Always a major show, this year’s edition was no exception with more than 800 hot rods and custom cars spread over two levels of the TCF Center.

Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s “Outlaw,” honored as one of the 20th Century’s most significant hot rods.

The most memorable display this year was immodestly (but quite accurately) labeled “The Most Significant Hot Rods of the 20th Century.” It was a veritable who’s who of iconic iron featuring tributes to Bob McGee’s ’32 Ford, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s “Outlaw” and “Beatnik Bandit,” Tommy Ivo’s ’25 T-Bucket, and Norm Grabowski’s ’22 T-Bucket – the last immortalized as Kookie Kookson’s ginchy ride in the TV show 77 Sunset Strip.

“Impressive” indeed. The 1963 Chevy wagon that won this year’s Ridler Award. (The chrome on those wheels practically glows!)

The biggest excitement always surrounds the Ridler Award, named for Autorama’s first promoter, Don Ridler. It’s the event’s top prize, and only cars that have never been shown publicly before are eligible. Judges select their “Great 8” – the eight finalists – on Friday and, for the rest of the weekend, excitement builds until the winner is revealed at the Sunday afternoon awards ceremony. The winner receives $10,000 and the distinction of having her or his name engraved forever on the trophy. It’s among the highest honors in the hot rod and custom car hobby. This year’s prize went to “Impressive,” a 1963 Chevrolet two-door station wagon built by a father-son-grandson team from Minnesota. With a Ridler now to its credit, no one can question the car’s name again.

Replica race cars – a Ford GT40 and a Ferrari 330 P3 used in the 2019 film Ford v Ferrari.

There’s always a little Hollywood magic on the show floor somewhere, and this year it came from a pair of replica cars used in two big racing scenes in the hit 2019 movie Ford v Ferrari. From the 1966 Daytona 24-Hour was the #95 Ford GT40 Mk. II driven by Walt Hansgen and Mark Donohue. From the 1966 Le Mans 24-Hour was the #20 Ferrari 330 P3 driven by Ludovico Scarfiotti and Mike Parkes. How accurate were the copy cars? Judge for yourself by looking here and here.

The Michigan Midget Racing Association introduces kids to the excitement of auto racing.

Those who are worried about younger generations not being interested in cars could take comfort from the Michigan Midget Racing Association. The organization’s Autorama display featured a half dozen cars that kids could (and did) climb into for photos. Quarter Midget cars are sized for kids anywhere from 5 to 16 years old. And while they look cute, these race cars aren’t toys. Their single-cylinder engines move the cars along at speeds up to 45 miles per hour. M.M.R.A.’s oval track in Clarkston is surfaced with asphalt and approximately 1/20 of a mile long.

Our 2020 Past Forward Award winner – a 1964 Pontiac GTO that matured with its owner.

Each year, The Henry Ford proudly presents its own trophy at Autorama. Our Past Forward Award honors a vehicle that combines inspirations of the past with innovative technologies of the present. It exhibits the highest craftsmanship and has a great story behind it. This year’s winner put a novel spin on the “Past Forward” concept. It’s a 1964 Pontiac GTO owned by Fred Moler of Sterling Heights, Michigan. Fred bought the car while he was in college and, appropriately for someone at that young age, drove it hard and fast. When adult responsibilities came along, he tucked the Goat away in a barn. Some 40 years later, Moler pulled the car out of the barn for restoration. He wanted to relive his college days but knew that neither he nor the GTO were the same as they were decades ago. Moler kept the trademark 389 V-8 but replaced the drivetrain with a more sedate unit. He added air conditioning, improved the sound system, and ever so slightly tinted the glass. In his own words, Moler enhanced the car to make it comfortable for his “more mature” self. He brought a piece of his own past forward to suit his present-day wants and needs. Like I said, a great story.

Autorama’s oldest entry – an 1894 horse-drawn road grader.

Autorama veterans know that the grittiest cars are found on TCF Center’s lower level – the infamous domain known as Autorama Extreme. Here you’ll find the Rat Rods that take pride in their raw, unabashedly unattractive appearance. By all means, take the escalator downstairs. There are always gems among the rats. This year I was thrilled to find an 1894 horse-drawn road grader manufactured by the F.C. Austin Company of Chicago. Utilitarian vehicles like this are rare survivors from our pre-automobile age. Autorama Extreme is a great place to tap your feet as well. Live music fills the lower level throughout the weekend – lots of 1950s rockabilly, of course, but plenty of blues and soul too.

Don’t miss Toy-a-Rama with its assortment of vintage car books and brochures.

Each year, I make a point of visiting Toy-a-Rama at the back of TCF Center. Vendors sell hundreds of plastic model kits, diecast models, memorabilia, and toys. But it’s the great selection of auto-related books, magazines, and vintage sales literature that always reels me in – and leaves my wallet a little lighter on the way out.

A beautiful 1:1 scale model of “Uncertain-T” – some assembly required.

And speaking of model kits, maybe the coolest thing I saw all weekend was down in Autorama Extreme. It was a beautifully crafted, partially-assembled model of Steve Scott’s “Uncertain-T” just like Monogram used to make – but this one was life-sized. Really, the giant sprue was terrific enough, but the giant hobby knife and glue tube took the whole thing to the next level. (Skill Level 2, as the box might’ve said.)

All in all, another great year celebrating the wildest, weirdest, and winningest custom cars and hot rods around. If you’ve never been, make sure you don’t miss Autorama in 2021.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

21st century, 2020s, toys and games, racing, Michigan, Detroit, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson, Autorama

Ford’s Mode:Flex Bicycle: Automakers Go Multimodal

While the concept of the e-bike has been around since the 1890s, it was not until the 1990s that battery, motor, and materials technology had advanced to the point where motorized bicycles became practical. While fully motor-driven units do exist, most e-bikes are of the “assist” variety. The rechargeable battery-powered motors on these bikes aren’t intended to replace muscle. Rather, they deliver a boost on steep hills or provide a few moments’ rest for a fatigued pedaler. The motors supplement rather than supplant human effort.

The Henry Ford acquired its first examples of electric-assist bicycle technology in 2017, with two prototype bicycles from Ford Motor Company’s Mode:Flex project. This 2015 initiative came out of the company’s efforts to position itself as a “mobility provider” for a post-car future. With the millennial generation returning to cities and, to some extent, turning away from automobiles in favor of public transit and other alternative forms of transportation, Ford charged teams of designers and engineers to create prototype bicycles specifically tailored for its automobile customers.

One of two Mode:Flex units acquired by The Henry Ford in 2017, this prototype bicycle is fully functional and capable of carrying a rider. Made of mostly steel, it weighs around 80 pounds – considerably heavier than a typical road bike’s 20-30 pounds. Bruce Williams, who led the Mode:Flex project, contended that the weight could be halved by using different materials if the bicycle ever went into production. THF172635

The Mode:Flex team – led by Bruce Williams, a Senior Creative Designer who had previously worked on the redesign of Ford’s F-150 pickup – developed a concept for a jack-of-all-trades bicycle that is easily disassembled for compact storage in any Ford vehicle. The front and rear ends are interchangeable between city, road and mountain bike configurations. (The bike’s seat post, which houses its 200-watt electric motor and rechargeable battery, remains the same in any configuration.)

The Mode:Flex connects to an app that controls the electric-assist motor; operates the LED headlight, taillight and turn signal (inspired directly by the units on the Ford F-150); and provides speedometer and trip odometer functions, navigation assistance, and real-time traffic updates. Running in “No Sweat” mode, the app monitors a user’s heart rate. When the heart rate climbs, the bicycle’s electric motor kicks in with a corresponding level of assistance, allowing novice bikers to ride to work in standard office attire (rather than Lycra or Spandex).

This non-functional mock-up of the Mode:Flex bicycle was largely created from thermoplastic materials rendered on a 3D printer. Built for promotional display purposes only, it lacks a working motor and is unable to support the weight of a rider, but it clearly illustrates the Mode:Flex bike’s foldability. THF172637

While the Mode:Flex could be used as a commuter’s sole mode of transportation, it is particularly geared toward those making multi-modal commutes. Someone might drive in from a distant suburb, park in a satellite lot outside the urban core, and then bike the “last mile” to work, shopping or entertainment. The bicycle’s app is designed to work seamlessly with an owner’s car as well. It can lock and unlock doors, monitor gas mileage or electric vehicle charging, track parking locations and perform other similar functions. The bicycle’s battery can be pulled out for remote charging or connected directly to a Ford vehicle’s electrical outlet.

The Mode:Flex bikes in The Henry Ford’s collection are concept prototypes, and Ford has no immediate plans to put them into production. Nevertheless, they represent concrete efforts by automakers to broaden their product lines and customer bases in response to evolving trends in personal transportation.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

design, 21st century, 2010s, Ford workers, technology, Ford Motor Company, by Matt Anderson, bicycles

Starting a drag race at the first NHRA national championship meet, Great Bend, Kansas, 1955. (THF122645)

If you’ve visited Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in the past several months, then you’ve undoubtedly noticed the large construction walls in the museum’s northeast corner, just behind Driving America. That 24,000 square-foot space will soon be home to our newest exhibit, Driven to Win: Racing in America presented by General Motors.

Racing gloves worn by Danica Patrick while competing in NASCAR’s Monster Energy Cup Series, 2016-2017. (THF176306)

Driven to Win will be among the most comprehensive looks at automobile racing in the United States. We’ll cover every major American racing type, and we’ll do it from 1895 – when the Chicago Times-Herald sponsored the country’s first formal auto race – right up to the present day. We’re featuring 26 vehicles in the show, including some old favorites and a few new surprises. We’ll also have more than 225 artifacts from the museum’s collection – many of them newly acquired for this exhibit.

George Heath driving his winning Panhard #7 at the first Vanderbilt Cup race, 1904. (THF277321)

Guests entering Driven to Win will first encounter what we call the “Dawn of Racing” where they’ll learn about American racing’s earliest days, whether on repurposed horse tracks or requisitioned public streets. Fittingly, the first vehicle they’ll see in this section is a successful little racer built and driven by a certain Henry Ford, the 1901 Ford Sweepstakes.

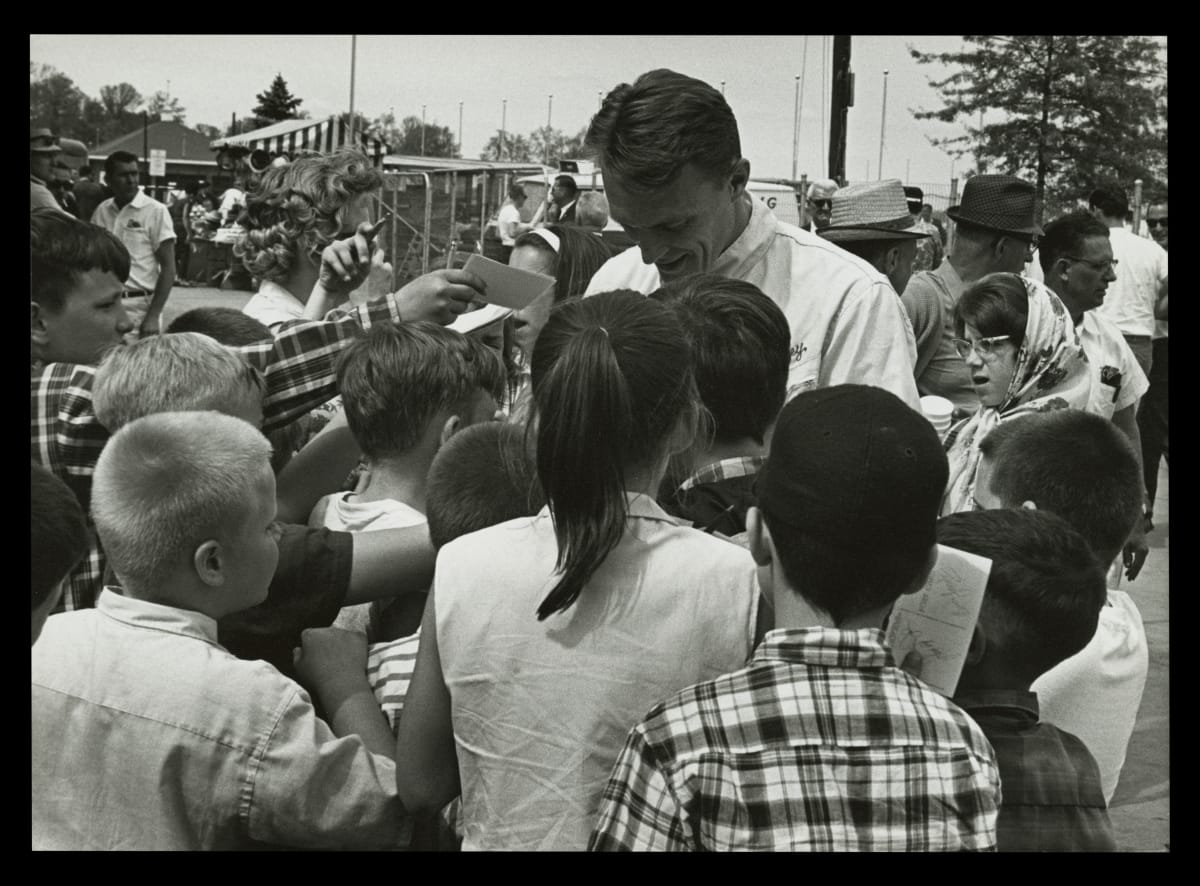

Dan Gurney signing autographs for young fans at the Indianapolis 500, 1966. (THF110522)

Just behind this introductory zone, we talk about “Igniting the Passion.” We’ll see some of the ways in which young people are introduced to motorsport through toys and games. Some of them will go on to become lifelong fans. Others might take up racing-inspired hobbies like tether cars. A few may go on to careers in the sport, whether behind the wheel, behind the pit wall, or behind the scenes. This area also serves as the entrance to our film experience, which forms the literal and figurative center of the exhibit. Inside, audiences will enjoy the sights, sounds, and spectacle of race day, and be inspired by young people pursuing dreams at legendary locations like Daytona, Indianapolis, and Bonneville.

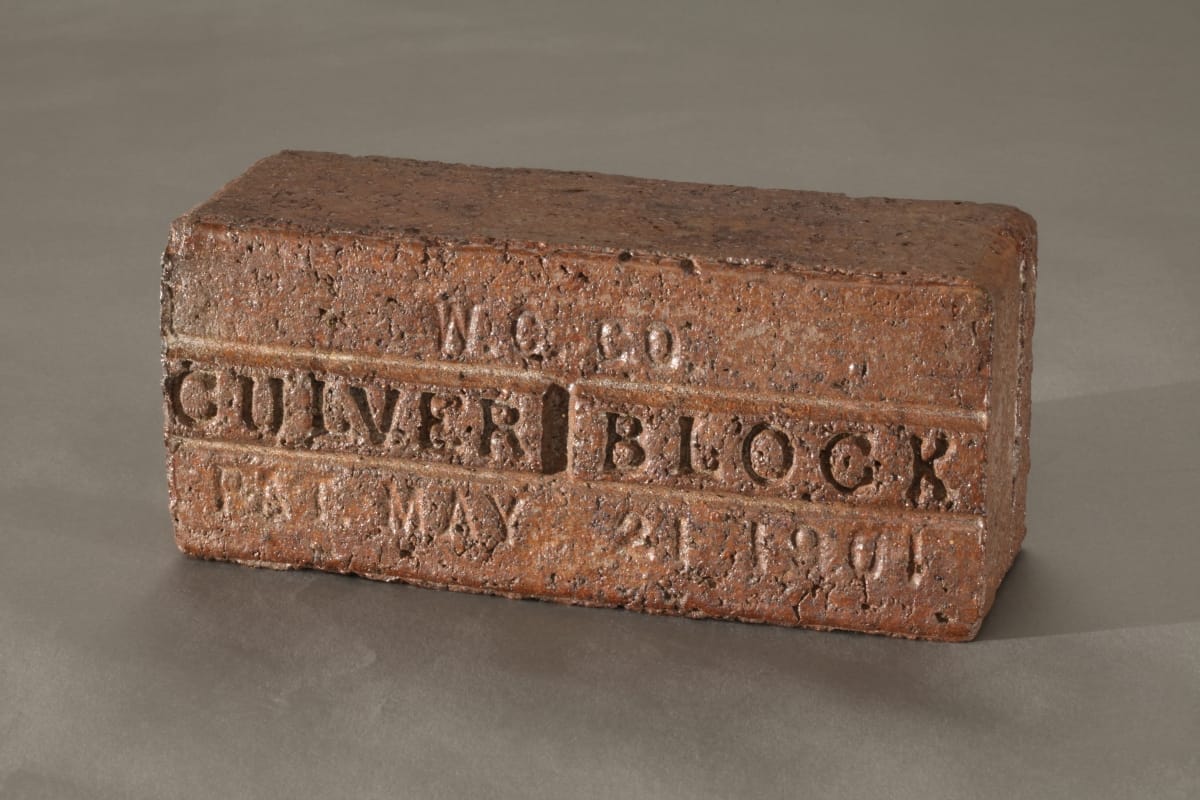

One of the 3.2 million bricks used to resurface Indianapolis Motor Speedway in 1909. (THF152054)

Outside the film theater, visitors can step into The Henry Ford’s own Winner’s Circle presented by Rolex. Here they’ll see the innovative and influential cars that changed the game. They’ll find the 1956 Chrysler 300-B from Carl Kiekhaefer’s phenomenal Mercury Marine team, which dominated NASCAR in the mid-1950s. Nearby is the Penske PC-17 that Rick Mears drove to victory in the 1988 Indianapolis 500, giving him the third of his record-tying four Indy wins – and Team Penske the seventh of its astounding 18 Indy victories. (The Chevrolet-powered Penske chassis is loaned to us courtesy General Motors, the exhibit’s presenting sponsor.)

Bobby Unser charging up Pikes Peak on his way to victory, 1962. (THF218104)

Moving around the exhibit’s perimeter, visitors will encounter the major forms of racing popular in the U.S. They’ll learn about land speed racing at Bonneville, where Goldenrod topped 409 mph in November 1965; they’ll see hill climbing at Pikes Peak, where Bobby Unser and his legendary family reigned supreme; they’ll visit the ceremonial heart of American racing at Indianapolis, where Harry Miller designed some of early racing’s most beautiful (if not always successful) open-wheel racing cars; they’ll travel overseas to Le Mans, where Ford Motor Company raced American sports cars in the 1960s and the 2010s; they’ll visit Daytona, birthplace of NASCAR and home to one of the country’s greatest stock car tracks; and they’ll see an homage to the vanished Detroit Dragway, where gassers and rail jobs once battled for the title of Top Eliminator.

Lyn St. James instructing young students at her Complete Driving Academy, 2008 (THF58563)

But racing isn’t just about the cars, it’s about the people behind them. Driven to Win visitors will have the chance to train using some of the same methods as today’s top drivers. There’s strength training with special machines that mimic muscle motions in a race. There’s neurocognitive training with interactive stations that test vision, memory, and reaction time. We’ll also have a pit crew activity where visitors can try their hand changing tires and refueling cars – though probably not in the 15 seconds it takes a top NASCAR crew. And for those eager to get behind the wheel, we’ll have a set of sophisticated simulators that are about as close to driving a hot lap as you can get without wearing a helmet.

Running the measured mile at Bonneville, circa 1950. (THF238926)

It’s been a long time coming, but Driven to Win: Racing in America promises to be worth the wait. Its blend of exciting immersive experiences will be unlike anything else in Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation – or in any other automotive museum, for that matter. We couldn’t be prouder of the work we’ve put into it, and we look forward to sharing the results with everyone this summer.

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. See more racing artifacts in our collection in this expert set.

21st century, 2020s, Michigan, Dearborn, racing, race cars, race car drivers, Henry Ford Museum, Driven to Win, by Matt Anderson

Celebrating Early Sports Cars at Old Car Festival 2019

This 1930 Hupmobile Model S was one of nearly 800 vehicles that filled Greenfield Village for this year’s Old Car Festival.

Another summer car show season is in the books as we wrap up our 69th annual Old Car Festival in Greenfield Village. We enjoyed practically perfect weather, enthusiastic crowds, and a field of nearly 800 vintage automobiles, trucks, motorcycles, and bicycles. You couldn’t have asked for a better weekend – or a better way to spend it.

This 1925 Ford Model TT truck fit perfectly with the Depression-era Mattox Family Home. Greenfield Village provides an incomparable setting for Old Car Festival.

Our spotlight for 2019 shined on early sports cars, whether genuine performers like the Stutz Bearcat, or mere sporty-looking cars like Ford’s Model T Torpedo Runabout. We usually associate sports cars with postwar imported MGs or all-American Corvettes, but enthusiast motoring is an old idea. For as long as there have been cars, there have been builders and buyers dedicated to the simple idea that driving should be fun.

The Henry Ford’s 1923 Stutz Bearcat. Many consider the Bearcat to be America’s first true sports car.

In keeping with the theme, we featured three sporty cars in our special exhibit tent across from Town Hall. From The Henry Ford’s own collection, we pulled our 1923 Stutz Bearcat. If there’s one name synonymous with early sporting automobiles, it’s “Bearcat.” Indianapolis-based Stutz introduced the model in 1912. The first-generation Bearcat featured only the barest bodywork and a trademark “monocle” windshield. Our later model was a bit more refined but, with 109 horses under the hood, it had no problems pushing the speedometer needle to the century mark. And, with its $3500 price tag, it had no problems pushing your bankbook into the red, either.

The sporty, affordable 1926 Chevrolet – for when the heart says, “speed up” but the wallet says, “slow down.”

Our good friends at General Motors once again shared a treasure from the company’s collection. This time it was a beautiful 1926 Chevrolet Superior Series V. The car boasted custom bodywork from the Mercury Body Company of Louisville, Kentucky. The speedster body and disc wheels gave a sporty look to a car targeted at budget-minded buyers. The Chevy sold for $510 – about one-seventh the cost of that Stutz!

This newly-restored 1927 Packard ambulance served the city of Detroit for nearly 30 years.

Every car at Old Car Festival has its own story, but some of them are particularly special. You could certainly say that about the 1927 Packard ambulance bought to us by owner Brantley Vitek of Virginia. He purchased the vehicle, in rather rough condition, at the Hershey swap meet in 1974. Dr. Vitek planned to restore it but, as is sometimes the case for car collectors, life got in the way. He wasn’t able to start the project until 2016, but it was well worth the wait. The finished ambulance is gorgeous – and not without southeast Michigan ties. The Packard served all its working life with the Detroit Fire Department. Old Car Festival wasn’t just a debut for the completed project, it was a homecoming as well.

The corn boil was just one of the dietary delights offered at this year’s show.

Veteran Old Car Festival attendees know that the show mixes a little gastronomy with its gasoline. Each year brings historically-inspired foods to the special “Market District” set up along the south end of Greenfield Village’s Washington Boulevard. Offerings for 2019 included turkey legs, sliced pastrami sandwiches, baked beans and cornbread (served in a tin cup), and peach cobbler. Longstanding favorites like kettle corn, hobo bread, and frozen custard were on hand too.

Prize winners received glass medallions handcrafted in the Greenfield Village Glass Shop.

As it does every year, Old Car Festival wrapped up with the Sunday afternoon awards ceremony. Show participants are invited to submit their vehicles for judging. Expert judges award prizes based on authenticity, quality of restoration, and the care with which each vehicle is maintained. First, second, and third-place prizes are awarded in eight classes, and one Grand Champion is selected for each of the show’s two days. Additionally, two Curator’s Choice awards are given to significant unrestored vehicles.

The Canadian Model T Assembly Team entertained by putting together this vintage Ford in mere minutes.

Year after year, Old Car Festival provides sights, sounds, and tastes to delight the senses. It’s no wonder the show has been going strong for 69 years. We’ll see you for show number 70 in 2020!

Matt Anderson is Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford.

Michigan, Dearborn, 21st century, 2010s, Old Car Festival, Greenfield Village, events, cars, car shows, by Matt Anderson