What If

Fueled with profound originality and resourcefulness, a twentysomething idealist changed the world with a machine built from the cheapest parts he could find. Our first computers were born not out of greed or ego, but in the revolutionary spirit of helping common people rise above the most powerful institutions. Steve Wozniak

An Early Electrical Charge

Nearly 20 years before he became famous for designing the first affordable personal computer, Steve Wozniak asked his father, who was an engineer, to explain why lightbulbs glow. From the clamps and coiled carbon filament to the vacuum bulb and passage of electrical current through the wires, the young Wozniak wanted to understand everything.

Replica of Thomas Edison's First Electric Lamp, Made in Greenfield Village

Artifact

Photographic print

Date Made

10 February 1969

Summary

The first practical incandescent electric lamp was successfully tested at Thomas Edison's Menlo Park Laboratory in 1879. Fifty years later, Edison re-enacted this event at the reconstructed Menlo Park complex in Greenfield Village. Edison presented the recreated bulb - seen in this photograph - to his friend Henry Ford.

Object ID

84.1.1630.P.B.51246

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Replica of Thomas Edison's First Electric Lamp, Made in Greenfield Village

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

"[My father] went back to the beginning, explaining to me how Thomas Edison invented lightbulbs," Wozniak recalled in his autobiography "iWoz". The lesson taught him the basics of physics and how electricity works at the atomic level: "[T]he more electrons that go through the wire—that is, the higher the current—the brighter the bulb will glow."

Wozniak, of course, is celebrated for his role helping to ignite our own modern-day technological revolution. As co-founder of the Apple Computer company with Steve Jobs, he is credited with the engineering ingenuity that led to Apple's early success.

A ‘Breakout’ Moment

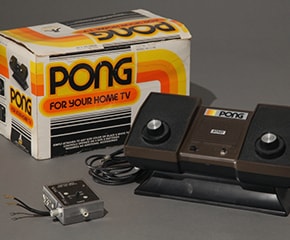

Although Wozniak did not invent the personal computer, he was the first to build affordable desktop machines that ordinary people could use. How this happened is a fabled story. Students at the same high school in northern California, Wozniak and Jobs were friends (though they were separated in age by five years, they’d had the same high school electronics teacher). In the early 1970s, they teamed up on a number of electronic ventures. The first gained them fame as geeky pranksters, as they figured out how to use a blue box to make free long-distance telephone calls (an illegal activity also known as phone phreaking). Not long after that, they designed a video game that was a close cousin of Atari’s wildly popular Pong (Jobs worked for Atari at the time and brought in Wozniak as a consultant). The game Jobs and Wozniak designed was called, aptly, Breakout. Not long after that, Wozniak invented a machine—the Apple 1—that broke away from the standard model of computer design.

Connectivity Nobody Else Could Imagine

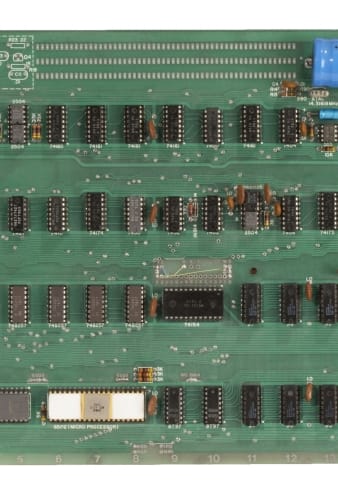

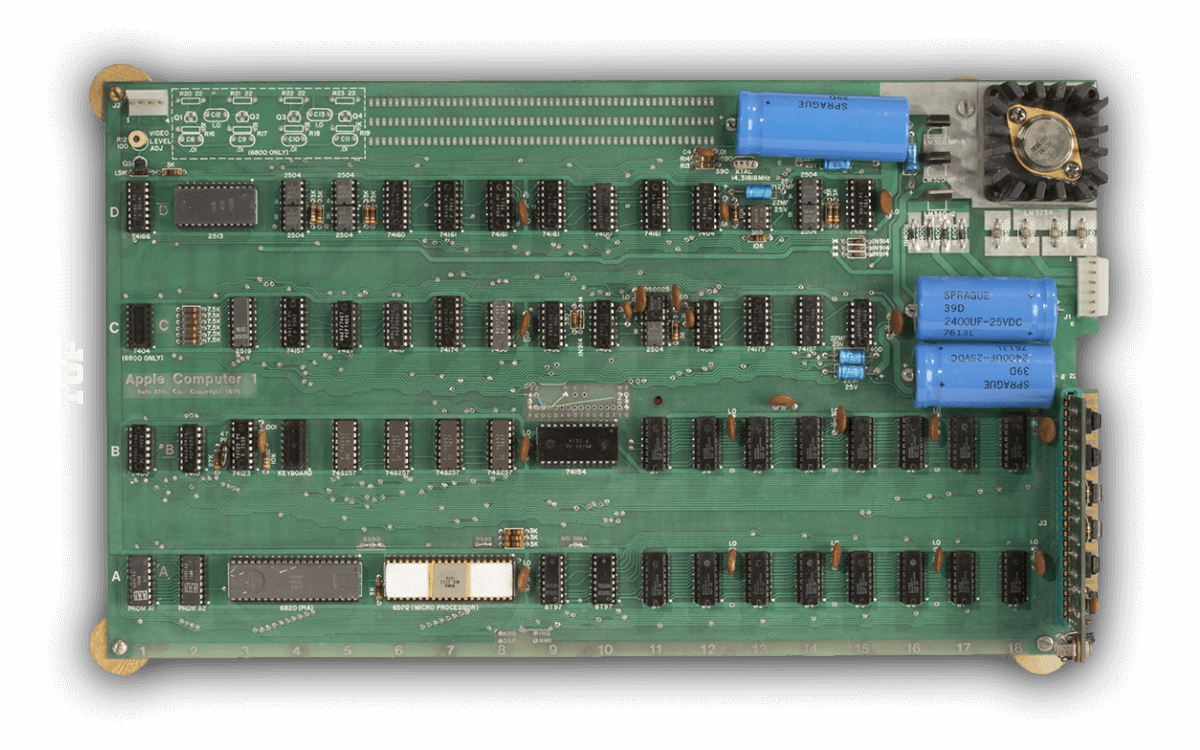

Even if you didn’t know anything about computers, or about their intricately designed digital circuits, or about the hidden binary world of 1s and 0s coded on tiny chips that make computers compute, you would’ve known that there was something different about Wozniak’s Apple 1 simply by looking at it. At a time when most computers were refrigerator-sized or larger, Wozniak’s hand-built computer was breathtakingly small, featuring a single circuit board. Wozniak could also "talk" directly to his machine by typing commands on a keyboard and reading feedback on a TV screen, which was far easier than interfacing with punch cards, clunky teletype machines, or panels with toggle switches and blinking lights.

If you did know a thing or two about computers—as did the electronic enthusiasts gathered for a meeting of Homebrew Computer Club in 1975, where Wozniak first showed off his Apple 1—you would have been dazzled by much more: How was it possible that Wozniak had built it with only a few dozen chips on a single circuit board (most of the emerging microcomputers at the time were designed with multiple boards and many more chips)? Did that MOS Technology 6502 microprocessor (which contained the central processing unit) really cost only $25, about $150 less than the popular Intel 8080 or Motorola 6800? And had he really installed a little program on those tiny read-only memory chips—that is, the chips that retain information even when the power is off—so that the computer would know how to boot up and automatically interface with the keyboard?

"People who saw my computer could take one look at it and see the future," Wozniak wrote in his autobiography. "And it was a one-way door. Once you went through it, you could never go back."

Stepping Into an Uncertain Future

At first, very few people wanted to follow Wozniak into that uncertain future. He tried to give his machine away—not the hardware and software, but his design specs, schematics, and code. Everything the other techie do-it-yourselfers would need to build it themselves. "I took it as my goal to design a very simple, affordable computer, which I knew how to do, and give it to the others," Wozniak said in an interview with The Henry Ford for its Collecting Innovation Today Oral History Project. "And I did, I passed it out for free. No copyright notices, no nuthin.’"

HP-35 Scientific Calculator, 1973

Artifact

Calculator

Date Made

1973

Summary

In 1971, William Hewlett challenged his engineers to miniaturize the company's 9100A Desktop Calculator--a forty-pound machine--into a device small enough to fit into his shirt pocket. The result--the HP-35--was the world's first handheld scientific calculator. It was expensive, but its powerful processing capabilities made it a rapid success, causing the swift abandonment of the slide rule.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

2014.67.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gft in Memory of Professor John M. Hayes.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

HP-35 Scientific Calculator, 1973

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

With Wozniak unable to find many people interested in his Apple 1 blueprints, Jobs, showing his early genius for converting invention into product, suggested they sell ready-made printed circuit boards. Even starting small, with the idea that they would sell boards to club members, friends and a few shops, the cost of the first production run was almost more than they could afford. In a fundraising move that’s become legendary, Wozniak sold his beloved HP scientific calculator, Jobs his Volkswagen van, and together they raised the $1,300 they needed to get started.

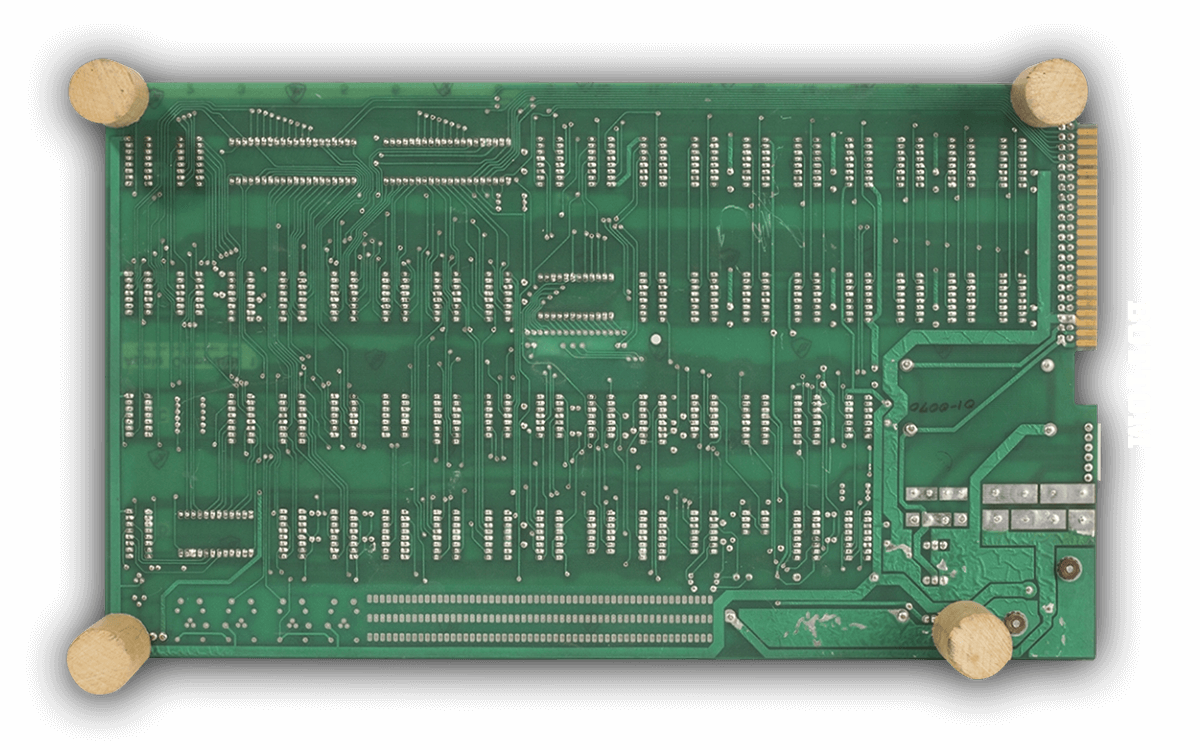

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

Artifact

Computer

Date Made

1976

Summary

This is one of the first 50 Apple 1 computers. Apple 1s were the first pre-assembled personal computers; Steve Wozniak assembled this one in Steve Jobs's family home. Before the release of the Apple 1, owning a personal computer meant building it yourself. Wozniak's refined engineering skills, coupled with Jobs's bold marketing abilities, led to a revolutionary and affordable product--as well as a successful company.

Creators

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

2014.113.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Eventually the Apple 1 expanded to include printed circuit boards pre-assembled with all the components. A local computer store placed an order for 50 units. Given their limited financial resources, it’s not surprising that Wozniak and Jobs did not package the Apple 1 with a power supply, case, monitor, and keyboard. But at the time the omission of these parts did surprise The Byte Shop owner, Paul Terrell, when the first lot of Apple 1s arrived at his store. "He had expected something more finished," author Walter Isaacson wrote in his biography Steve Jobs. "But Jobs stared him down, and he agreed to take delivery and pay."

Those original Apple 1s retailed for $666.66 ("as a mathematician, I like repeating digits," Wozniak has said by way of explanation). In today’s dollars, that’s about $2,800, relatively cheap for a microcomputer at the time. Less than a year later, Wozniak had re-imagined his Apple 1, considerably improving on it with the introduction of the Apple II. This machine was far more advanced and elegantly designed than the Apple 1, supporting color display and featuring a single case with a built-in keyboard, mouse, and integrated power supply.

Pursuing & Preserving Innovation

With more than 4 million units sold between 1977 and 1993, the Apple II is considered by many to be one of the best personal computers of all time. Its spectacular success is a tribute to Wozniak’s brilliance as an engineer, his drive to keep iterating and improving on an already visionary design. But it is also a sign of the times in which we’re living: The latest pioneering technology always steals the glory from innovations that come before.

"Devices often land in the dustbin before they are given the opportunity to be considered as objects relevant to future museumgoers," says Communications and Information Technology Curator Kristen Gallerneaux, who traveled to New York City’s Bonham auction house in February 2015 to acquire an original Apple 1 computer for The Henry Ford for a record-breaking $905,000. "The Apple 1 is especially precarious in this way: when the Apple II was released in 1977, an exchange program allowed Apple 1 buyers to mail their original purchase in for an upgrade. Many Apple 1’s were scrapped as a result."

Devices often land in the dustbin before they are given the opportunity to be considered as objects relevant to future museumgoers.

Kristen Gallerneaux

Communications and Information Technology Curator, The Henry Ford

Kristen Gallerneaux

Communications and Information Technology Curator, The Henry Ford

The Apple 1 The Henry Ford acquired is one of the original machines sold to The Byte Shop, and one of the few still fully operational. With its vintage Sanyo monitor and crudely constructed wooden box for the power supply, the antiquated look of this Apple 1 can make the brilliance of Wozniak’s invention seem impossibly distant and remote from our own modern lives, with our moment-by-moment dependence on keys and screens and connectivity.

That is, until we step back in time to join Wozniak on a summer night nearly forty years ago, when he was in the final moments of finishing his computer. After debugging a program, he tapped a few keys and at last letters appeared on his little black-and-white TV screen. As he wrote in his book, "It was the first time in history anyone had typed a character and seen it show up on their own computer’s screen right in front of them." The machine had 4K of RAM, an impressive amount of random access memory at the time. Today that’s only enough to send a short text, nothing much longer than "Hello, world."

Browse Collections

Atari Pong Game, circa 1975

Artifact

Video game

Date Made

circa 1975

Summary

Pong, a simple video Ping-Pong game, started in 1972 as an early and incredibly popular arcade game. Manufacturer Atari, under its legendary co-founder Nolan Bushnell, released a home version of the game through Sears in 1975. One of the first successful home video games, Pong paved the way for this new leisure activity for kids and adults.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

99.114.1.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Atari Pong Game, circa 1975

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

Artifact

Computer

Date Made

1976

Summary

This is one of the first 50 Apple 1 computers. Apple 1s were the first pre-assembled personal computers; Steve Wozniak assembled this one in Steve Jobs's family home. Before the release of the Apple 1, owning a personal computer meant building it yourself. Wozniak's refined engineering skills, coupled with Jobs's bold marketing abilities, led to a revolutionary and affordable product--as well as a successful company.

Creators

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

2014.113.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Apple 1 Computer, 1976

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

DEC PDP-11/20 Minicomputer, 1970

Artifact

Minicomputer

Date Made

1970

Summary

Digital Equipment Corporation's PDP 11 computers were popular, widely used machines in the era before personal computers. These 16-bit minicomputers ("mini" as opposed to the room-sized mainframe computers of the 1950s and '60s) were relatively inexpensive and were used for business (payroll, accounting), scientific, educational, and timesharing purposes. Many Americans were introduced to computing through PDP 11s installed at schools and offices beginning in 1970.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

90.295.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Donald P. Bilger

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

DEC PDP-11/20 Minicomputer, 1970

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Manual, "INTEL 8080 Microcomputer Systems User's Manual," 1975

Artifact

Manual (Instructional materials)

Date Made

September 1975

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

95.22.2.3

Credit

From the collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of O. S. Narayanaswamy.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Manual, "INTEL 8080 Microcomputer Systems User's Manual," 1975

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Volkswagen Beetle Ignition Key, 1952-1959

Artifact

Ignition key

Date Made

1952-1959

Summary

This ignition key, with the VW insignia in its head, might have been used for a Volkswagen Beetle or van.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

2011.170.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Volkswagen Beetle Ignition Key, 1952-1959

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Apple Personal Computer, Model IIe, circa 1977

Artifact

Microcomputer

Date Made

circa 1977

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

2001.140.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Edward J. Tumas.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Apple Personal Computer, Model IIe, circa 1977

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Apple Personal Computer, Model IIGS, 1986-1992

Artifact

Microcomputer

Date Made

1986-1992

Summary

The Apple IIGS improved upon Apple's first mass market PC, the Apple II. The "GS" relates to its excellent graphics and sound capabilities. It was also one of the first Apples to use a mouse and a color graphical user interface. This system was popular among educators; this IIGS was used in a Detroit classroom in the late 1980s.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

2009.4.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Mildred and Charles Webster

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Apple Personal Computer, Model IIGS, 1986-1992

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Unloading and Unpacking of Apple 1 Computer, November 2014 - Image 35

Details

Details

Unloading and Unpacking of Apple 1 Computer, November 2014 - Image 35

Artifact

Digital photograph

Date Made

25 November 2014

Summary

November 25, 2014, was an exciting day at The Henry Ford. These images capture the arrival of a new acquisition--a 1976 Apple 1 computer. This particular Apple 1 was one of the first 50 ever assembled by Steve Wozniak, at the home of Steve Jobs. Its functioning motherboard was accompanied by hardware, schematics, and a historical document collection.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

EI.1929.853

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Unloading and Unpacking of Apple 1 Computer, November 2014 - Image 35

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Replica of Thomas Edison's First Electric Lamp, Made in Greenfield Village

Artifact

Photographic print

Date Made

10 February 1969

Summary

The first practical incandescent electric lamp was successfully tested at Thomas Edison's Menlo Park Laboratory in 1879. Fifty years later, Edison re-enacted this event at the reconstructed Menlo Park complex in Greenfield Village. Edison presented the recreated bulb - seen in this photograph - to his friend Henry Ford.

Object ID

84.1.1630.P.B.51246

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Replica of Thomas Edison's First Electric Lamp, Made in Greenfield Village

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

HP-35 Scientific Calculator, 1973

Artifact

Calculator

Date Made

1973

Summary

In 1971, William Hewlett challenged his engineers to miniaturize the company's 9100A Desktop Calculator--a forty-pound machine--into a device small enough to fit into his shirt pocket. The result--the HP-35--was the world's first handheld scientific calculator. It was expensive, but its powerful processing capabilities made it a rapid success, causing the swift abandonment of the slide rule.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

2014.67.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gft in Memory of Professor John M. Hayes.

Location

Not on exhibit to the public.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

HP-35 Scientific Calculator, 1973

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Discussion Questions

- What or who motivated Steve Wozniak to innovate?

- What traits of an innovator did Steve Wozniak illustrate?

- Which of these traits do you think was most important to his success inventing the Apple 1?

- What are some of the problems of today, and what innovator traits could you apply to solve them?

- Do you think you can be an innovator like Steve Wozniak? Why or why not?

Fuel Your Enthusiasm

The Henry Ford aims to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic artifacts, stories and lives from America’s tradition of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation. Connect to more great educational resources: