What If

Lessons about the trials and triumphs of innovation from the days just before Ford finished building his Quadricycle Obstacles are those frightful things you see when you take your eyes off the goals. Henry Ford

A Glimpse of Invention

Shortly before midnight on a March evening in 1896, just a few months shy of his thirty-third birthday, Henry Ford witnessed another inventor driving a gas-powered vehicle in Detroit. Charles Brady King—a Cornell-trained engineer—was named the next day in the local newspapers for being the first in Detroit to design, build, and drive a self-propelled automobile. Ford didn’t have to read the articles for a detailed account of the event—he saw the test run in person, pedaling on his bicycle behind King’s vehicle as it motored down Detroit’s cobblestone streets.

Most everyone knows Henry Ford encountered plenty of obstacles as he rose from obscurity to become one of the most influential American innovators of the 20th century. Still, it’s hard to picture the pioneer of America’s transportation revolution pedaling behind another inventor’s car, just another cyclist in the crowd trying to glimpse an internal-combustion automobile—the very machine Ford himself was working feverishly to build.

'Frightful' Obstacles

1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

Artifact

Automobile

Date Made

1896

Summary

The Quadricycle was Henry Ford's first attempt to build a gasoline-powered automobile. It utilized commonly available materials: angle iron for the frame, a leather belt and chain drive for the transmission, and a buggy seat. Ford had to devise his own ignition system. He sold his Quadricycle for $200, then used the money to build his second car.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

00.2.93

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Henry and Clara Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

It took another three months before Ford completed his vehicle. When he took his “Quadricycle” out for a test drive in early June, there were no crowds on the streets waiting to see it, no journalists assembled to write about his invention. In retrospect, this was fortunate because his test run wasn’t nearly as successful as King’s.

The first problem he encountered was almost comical: Ready to roll his car out of his shed, Ford discovered it was too large to fit through the doors. “He grabbed an axe and doubled the opening by knocking out some bricks,” author Steven Watts writes in his best-selling biography The People’s Tycoon. Once the car was out on the streets, the engine broke down in front of the Cadillac hotel. “An inspection revealed only a minor problem—a spring supporting one of the electrical ‘ignitors’ had failed,” Watts writes. “And a quick repair got the vehicle up and running once again.”

Henry Ford with Co-Worker at Edison Illuminating Company, Detroit, Michigan, 1896

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

In 1891, Henry Ford left his small lumber business to work as a night engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit. By early 1894, he was promoted to chief engineer. The same year he posed for this photograph, Ford completed his first horseless carriage, the Quadricycle, with the help of some of his coworkers.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

84.1.1660.P.O.3029

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry Ford with Co-Worker at Edison Illuminating Company, Detroit, Michigan, 1896

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Anyone who chronicles the life of Henry Ford, from biographers to documentary filmmakers, points to Ford’s first ride in his Quadricycle as a triumphant moment for the inventor. More than just about any other event in Ford’s life, this moment marks the beginning of his ascent as an innovator. And yet at the time he surely faced tremendous doubts, too. Doubts that can be easy to downsize when we look back on the great span of his life. Doubts that might’ve amounted to those “frightful things” Ford was referring to in his famous quote about life’s obstacles.

Imagine Ford on that morning in 1896: Back from his maiden voyage in his first hand-built automobile, he had no time to celebrate. First, he rushed to repair the shed, which belonged to the landlord of the apartment he was renting on Bagley Avenue. Then he dashed off to his “day job” as an engineer with the Edison Illuminating Company, where he helped to maintain the coal-fed steam engines that generated electricity for the city of Detroit. He was scrambling to pay for the parts he needed for his Quadricycle, so much so that his wife Clara “wondered many times if she would live to see the bank account restored.”

A Late Bloomer

At the age of thirty-three, Henry Ford was far from achieving the kind of success he admired in one of his heroes, Thomas Edison. Edison was 22 when he received the first of his 1,093 U.S. patents, and by the time he was in his early thirties, he’d invented the phonograph and a long-lasting practical light bulb in his Menlo Park Laboratory.

"People don't realize that Henry Ford was kind of a late bloomer," says Bob Casey, former Curator of Transportation at The Henry Ford. "He left home when he was sixteen. He went to Detroit. He grew up on a farm but he didn’t want to be a farmer. He was interested in machinery and got a job in a machine shop…then he got fired from a couple of jobs. Sometimes he left on his own. But he was always learning, always doing stuff, and he built up this store of practical knowledge."

'Why Innovators Get Better With Age'

Henry Ford helps to dispel the myth that innovators make their mark on the world when they are young. Certainly this is true for some, including modern-day icons like Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak of Apple, Bill Gates of Microsoft, and Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook. But genius flourishes well past the age of twenty, as best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell helped to point out in his well-known 2008 New Yorker essay "Late Bloomers". More recently, a 2013 New York Times article (“Why Innovators Get Better With Age”) by Tom Agan noted that Nobel Prize winners typically make significant breakthroughs in their thirties.

1909 Ford Model T Touring Car

Artifact

Automobile

Date Made

1909

Summary

Henry Ford crafted his ideal car in the Model T. It was rugged, reliable and suited to quantity production. The first 2,500 Model Ts carried gear-driven water pumps rather than the thermosiphon cooling system adopted later. Rarer still, the first 1,000 or so -- like this example -- used a lever rather than a floor pedal to engage reverse.

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

57.77.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

1909 Ford Model T Touring Car

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Looking back through time, historians document many signature achievements in Henry Ford’s life—from his Model T, assembly line, and Five Dollar Day incentive to his monumental River Rouge plant—that mark him as one of America’s greatest innovators. He is celebrated for his ability to see before practically anybody else that he could transform modern America by building a durable, affordable car for ordinary citizens. What’s just as important to remember is that his genius was coupled with what Gladwell calls "forbearance and blind faith", and what others might call "grit". In other words, he never ever gave up. If ever there was a defining moment in his life when he first realized he possessed these resilient resources, it might’ve been those three months in 1896, when another engineer won recognition for building the first automobile in Detroit.

Inventors vs. Innovators

Ford’s vision for building an affordable, self-propelled vehicle was partly fueled by his desire to relieve the burden of hard farm labor, particularly plowing the fields, which was the life of his father and might’ve been his if he hadn’t followed his dreams. He also hoped automobiles would help to end the inherent isolation of rural, farm living. Ultimately, with the durable design of the Model T, Ford’s cars were capable of traveling across heavily rutted farm roads (and later, of course, he went on to produce tractors). Ford’s first prototype, the Quadricycle, was not only functional but considerably more lightweight than the car designed by Charles Brady King.

As those who study the lives of innovators know, there is an important distinction between invention and innovation. “An invention is something that is new and interesting,” says Casey. “An innovation is something new and interesting that gets widely adopted. If you can’t get it widely adopted, it may be cool, but it’s not an innovation because it’s not really affecting the lives of very many people.”

When we step into the mindset of an innovator, we can now imagine Ford’s pursuit of King and his vehicle through the cobblestone streets of Detroit in a very different light. We don’t see him as an inventor chasing after another inventor’s success. We see him as an innovator who knew that what might look like failure to some is really innovation about to bloom.

Browse Collections

Henry Ford Driving the Quadricycle near Cass Park in Detroit, 1896

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

This photograph shows Henry Ford, age 33, with his Quadricycle in Detroit in the fall of 1896. He built his first gasoline powered vehicle with help from some friends in a shed behind a house he and his wife, Clara, rented.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

84.1.1660.1218

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry Ford Driving the Quadricycle near Cass Park in Detroit, 1896

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

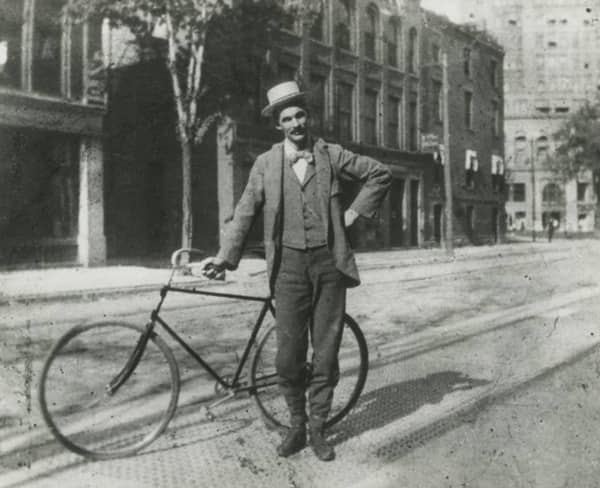

Henry Ford with a Bicycle, Detroit, Michigan, 1893

Artifact

Photographic print

Date Made

27 January 1935

Summary

In 1893 -- before he became famous -- Henry Ford rode his bicycle to work through the streets of Detroit.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

84.1.1660.P.O.423.B

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry Ford with a Bicycle, Detroit, Michigan, 1893

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford Driving His Quadricycle in Detroit, Michigan, 1896

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

This photograph shows Henry Ford, age 33, with his first gasoline-powered vehicle in October of 1896. He built the Quadricycle with help from some friends in a shed behind a house he and his wife, Clara, rented.

Creators

Object ID

84.1.1660.P.833.89114

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Related Objects

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry Ford Driving His Quadricycle in Detroit, Michigan, 1896

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Interior of Bagley Avenue Workshop in Greenfield Village, 1937

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

Henry Ford reconstructed the Bagley Avenue Workshop, the shed behind the duplex house at 58 Bagley where he and Clara had lived, in Greenfield Village in 1933. Ford built the 1896 Quadricycle, his first automobile, in the original shed. Photos of the original building and site guided the reconstruction. Bricks from the actual Bagley house reportedly were used in the replica shed.

Place of Creation

Object ID

EI.1929.P.833.67782.A

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Related Objects

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Interior of Bagley Avenue Workshop in Greenfield Village, 1937

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Henry and Clara Ford's Former Home on Bagley Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, Taken by Henry Ford, 1898

Details

Details

Henry and Clara Ford's Former Home on Bagley Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, Taken by Henry Ford, 1898

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

From late 1893 to mid-1897, Henry and Clara Ford rented the left-side half of this duplex house at 58 Bagley Avenue in Detroit. It was in the kitchen here where the couple tested Henry's first gasoline-powered engine in December 1893, and it was in the shed behind the house where Henry finished his first automobile, the Quadricycle, in June 1896.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

P.O.16062

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry and Clara Ford's Former Home on Bagley Avenue, Detroit, Michigan, Taken by Henry Ford, 1898

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

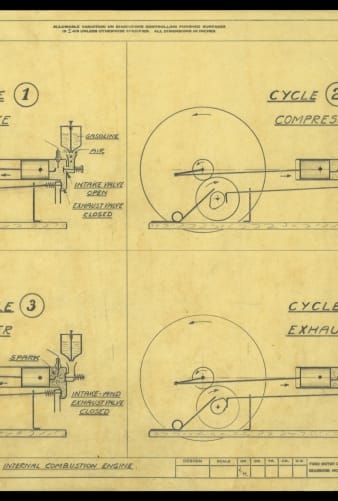

Drawing of the 1893 Kitchen Sink Engine, "Diagram of 4 Cycle Internal Combustion Engine"

Artifact

Technical drawing

Date Made

23 December 1934

Summary

Henry Ford built his first experimental engine using scrap metal for parts. He tested it on the kitchen sink after supper on December 24, 1893. For ignition he ran a wire from the ceiling's light bulb. His wife, Clara, hand fed the gasoline to the intake valve while Henry spun the flywheel. The engine roared into action, shaking the sink.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

64.167.181.4

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Drawing of the 1893 Kitchen Sink Engine, "Diagram of 4 Cycle Internal Combustion Engine"

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Bagley Avenue Workshop

Artifact

Workshop (Work space)

Date Made

1933

Summary

Henry Ford transformed the storage shed behind his family's rented duplex at 58 Bagley Avenue in Detroit into a workshop. Here, in 1896, he built his first car -- the "Quadricycle." In 1933, Ford reconstructed the shed in Greenfield Village. The original shed had been torn down, so he reportedly used bricks from a wall of the Bagley Avenue residence instead.

Place of Creation

Keywords

United States, Michigan, Detroit

Reconstructions (Visual works)

Object ID

33.707.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Bagley Avenue Workshop

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Employees at Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit, circa 1895

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

Henry Ford (far right) joined Edison Illuminating Company as a night engineer in September 1891. By mid-1894 he had been promoted to chief engineer. It was during his time here that Ford built his first automobile, the 1896 Quadricycle. Ford resigned from Edison Illuminating Company in August 1899 to devote himself full time to the budding automotive industry.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

84.1.1660.P.188.606

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Employees at Edison Illuminating Company of Detroit, circa 1895

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

Artifact

Automobile

Date Made

1896

Summary

The Quadricycle was Henry Ford's first attempt to build a gasoline-powered automobile. It utilized commonly available materials: angle iron for the frame, a leather belt and chain drive for the transmission, and a buggy seat. Ford had to devise his own ignition system. He sold his Quadricycle for $200, then used the money to build his second car.

Creators

Place of Creation

Object ID

00.2.93

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Henry and Clara Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

1896 Ford Quadricycle Runabout, First Car Built by Henry Ford

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Henry Ford with Co-Worker at Edison Illuminating Company, Detroit, Michigan, 1896

Artifact

Photographic print

Summary

In 1891, Henry Ford left his small lumber business to work as a night engineer at the Edison Illuminating Company in Detroit. By early 1894, he was promoted to chief engineer. The same year he posed for this photograph, Ford completed his first horseless carriage, the Quadricycle, with the help of some of his coworkers.

Creators

Keywords

Object ID

84.1.1660.P.O.3029

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford. Gift of Ford Motor Company.

Location

By Request in the Benson Ford Research Center

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

Henry Ford with Co-Worker at Edison Illuminating Company, Detroit, Michigan, 1896

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

1909 Ford Model T Touring Car

Artifact

Automobile

Date Made

1909

Summary

Henry Ford crafted his ideal car in the Model T. It was rugged, reliable and suited to quantity production. The first 2,500 Model Ts carried gear-driven water pumps rather than the thermosiphon cooling system adopted later. Rarer still, the first 1,000 or so -- like this example -- used a lever rather than a floor pedal to engage reverse.

Place of Creation

Keywords

Object ID

57.77.1

Credit

From the Collections of The Henry Ford.

Get more details in Digital Collections at:

1909 Ford Model T Touring Car

What is The Henry Ford?

The national attraction for discovering your ingenuity while exploring America’s spirit of innovation. There is always much to see and do at The Henry Ford.

Discussion Questions

- What or who motivated Henry Ford to innovate?

- What traits of an innovator did Henry Ford illustrate?

- Which of these traits do you think was most important to his success inventing the Quadricycle?

- What are some of the problems of today, and what innovator traits could you apply to solve them?

- Do you think you can be an innovator like Henry Ford? Why or why not?

Fuel Your Enthusiasm

The Henry Ford aims to provide unique educational experiences based on authentic artifacts, stories and lives from America’s tradition of ingenuity, resourcefulness, and innovation. Connect to more great educational resources: